My Grandfather, the Writer

How my grandfather’s career as a professional author inspired me to pick up a pen and begin my own.

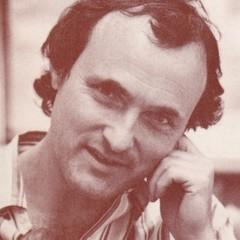

Here is my grandfather’s professional headshot from his time writing for ‘The New Yorker.’

My grandfather, Gerald Jonas, used to pick me up from Kindergarten on Wednesdays. I attended P.S. 84 then, a dual-language elementary school on 92nd street located just around the corner from the towering oak trees which line Central Park. I remember my kindergarten teacher, Ms. Nuñez, once asked us to write about which day of the week was our favorite day. Many of the students chose to write about Fridays because it was a half day; most chose to write about the weekend.

I chose to write about Wednesday because that was the day my grandfather (or “Bobo” as my cousins and I call him) would bring me to Whole Foods for a hot chocolate, or take me on a walk to see the Alice in Wonderland statue. To represent Wednesdays, I drew a picture of Bobo wearing his signature chambray button-up (which I colored in using Crayola’s cornflower blue crayon), and scribbled a few sentences containing quite a few backwards E’s (I could never get the direction right).

Despite its flaws, my grandfather hung up my argument delineating the superiority of Wednesdays in his study, on the wall right behind his desk. Every piece of writing I have ever produced for him ends up on that wall — whether it is a poem I wrote in the first grade about an anthill I discovered behind the playground, or a handwritten card that I gave him on his 80th birthday. In return, he shares his own writing with me — forwarding haiku cycles to my e-mail, or sending me links to his political op-eds. Whenever I find myself in his study, confronted by the dozens of pieces he has taped to the wall, I am reminded that my love of writing descends from his.

My grandfather grew up on Valentine Avenue in the Bronx, a quiet street that was home to many Jewish families. When he was old enough to attend school, his mother, Margaret Jonas, decided that he must attend Horace Mann, a prestigious private school in Riverdale which would set him up for collegiate success. Armed with the knowledge that many historically gentile private schools were beginning to admit Jewish students in the post-World War II political climate, Rose signed him up for an IQ test and used his score as leverage to get him accepted into the institution.

At just ten years old, he knew he wanted to become an author after penning short stories for his school’s newspaper inspired him to try his hand at professional writing. “I started writing science fiction at 13, and tried my luck submitting to leading Science Fiction magazines of the day. I ended up getting a little encouragement, and that sealed the deal.”

From Horace Mann, my grandfather attended Yale University where he immediately signed up to write for the campus newspaper. “Writing and editing for The Yale Daily News was crucial in determining the path of my career, as I sensed I wasn’t going to make a living writing fiction. I discovered that I could do journalism, and make a living from it, but my first love remained poetry,” he explained.

After college, his success as the Editor-in-Chief of The Yale Daily News led him to find a staff position as a writer for The New Yorker. “The New Yorker in my day — the 1960s through the early 90s — was in its heyday. The editor, William Shawn, was in total control [of what was published], but never a tyrant. Because it paid far better for most writing than the majority of other outlets, the competition for space in its pages was fierce,” he said.

“As a result, the atmosphere was a strange mixture of laidback and very tense. Some people thrived, some literally cracked up (I’ll spare you the grisly details!), and most fell somewhere in the middle like me.”

As he grew accustomed to the process of writing for The New Yorker, my grandfather began to become more comfortable with the routines of professional journalism. “I soon learned that the ability and willingness to ask basic questions as a journalist was key. Never pretend to know more than you do. You are representing the reader who is intelligent but not (yet) well informed. So don’t be afraid to look ‘dumb’ and find power in voicing your confusion! (Of course, first you have to do your homework, so you’re up to speed on the vocabulary and concepts),” Jonas said.

While Jonas wrote many poems and articles which went on to be featured in The New Yorker, he most often wrote for the Talk of the Town section, which is the first piece of writing readers see when they open the magazine.

“Talk of the Town was unique. You sometimes got assignments, but you could also make suggestions which were often ‘okayed’ [by the editors]. That didn’t guarantee they’d buy it, however. Sometimes the editors would pay for a piece and never run it. Sometimes you never heard a definitive ‘no’ but you slowly realized, as weeks went by with no answer, that it had been rejected. No wonder some people cracked up! In my early days, Talk pieces were published without bylines, so you had to alert friends as to which piece was yours. Otherwise, they’d have no clue!”

After ten years of writing non-fiction, research-based pieces for The New Yorker on subjects ranging from sports like basketball to his personal history with stuttering, Jonas “decided to concentrate on science for strategic career reasons.” Because he studied science in addition to philosophy in college, he was hired as the Science-Fiction critic for The New York Times, a position which required interdisciplinary knowledge and highlighted the value of a well-rounded liberal arts education.

When asked how he views the intersection between STEM and the humanities, Jonas replied, “Einstein once said (approximately), ‘the root of both art and science is mystery.’ With that point of view you can see the links between them.”

Jonas stresses that while a career in writing is incredibly rewarding, it can also be vulnerable. “Dealing with rejection is very difficult. Of course this isn’t unique to writing, but it seems especially baked into a writing career. Most who stick it out gravitate toward situations where the ratio of acceptance to rejection is high enough to sustain the individual, as I did by focusing on science and finding some outlets that were easier for me to sell to. But it also takes internal work,” he said.

“I remember a great insight I learned early on, when someone said, ‘Don’t take rejection personally; it’s not you that’s being rejected,’” Jonas continued. “This was followed later by an even greater insight: ‘If you’ve done the best you can, then it IS personal. They may not be right in their judgment but they are, in a sense, rejecting you. And you have to accept that and move on. If you can’t, you are in the wrong line of work.’”

“Finally, for me, writing successfully for a living involved collaboration — with editors, sharing criticism with colleagues, and asking for help. I found more of this collaborative approach outside The New Yorker rather than in it, which is why perhaps I found more pleasure elsewhere. But to each his own. Even for poetry, I like to run things through a writers’ group. I have been a member of such groups for some 50 years.”

In his retirement, my grandfather has wholeheartedly embraced the title of “poet.” In 2015, he published a collection of poetry called Epitaphs with his cousin Sandy Wurmfeld, whose artwork is featured in the book.

Gerald Jonas views poetry as an abstract expression of emotion which cannot be dictated by deadlines. “I have always been in awe of poets who say they sit down every day and write so many lines. Perhaps because my journalism involved constant deadlines I always thought of poetry as something that I only did when I felt ‘inspired’ — a fancy term which means finding a line of thinking emerge unprompted, and then seizing on it to follow wherever it might lead.”

“I have always been in awe of poets who say they sit down every day and write so many lines. Perhaps because my journalism involved constant deadlines I always thought of poetry as something that I only did when I felt ‘inspired’ — a fancy term which means finding a line of thinking emerge unprompted, and then seizing on it to follow wherever it might lead,” said Gerald Jonas.

Enza Jonas-Giugni is a Features Editor for 'The Science Survey,' where she edits long-form articles on topics ranging from politics to portraits of Bronx...