Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, and Émile Charmy.

Cubism, Fauvism, Modernism, and Impressionism.

Many artists, many styles – but only one art dealer.

In New York University’s Grey Art Museum lies an homage to Berthe Weill (1865-1951), a 20th-century Parisian art dealer who was regarded by many of her contemporaries as the “Mother of Modern Art.” From 1901 to 1941, Berthe Weill showcased the works of several then-unknown artists, putting her faith in their talent and taking enormous risks. The Grey Art Museum has devoted five months to the exhibition Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde showcasing both Weill and the artists that Weill promoted throughout her career, honoring her impeccable eye for young talent and her incredible diversity of clients. The exhibit is currently on view until Tuesday, March 1st, 2025.

Situated on rue Victor Massè in the 9th arrondissement, Berthe Weill’s art gallery, Galerie B. Weill, was in the center of Paris’ Pigalle district, known for its nightlife and entertainment. Just a short walking distance from the Moulin Rouge and the rest of Montmartre, a neighborhood in Paris known for its rich artistic heritage, Weill witnessed a number of ambitious artists in their early years looking for someone to give them a chance. In Marianne Le Morvan’s preface to Berthe Weill’s memoir Pow! Right in the Eye!, she describes Weill as having “promoted foreign artists, many of whom dared to break with conventions, before anyone else understood their bold experiments.”

Weill never committed to representing one singular art style at any point in her career, but rather showed interest in any work that she thought had potential. Just as Weill sold Picasso’s early sketches – which revealed his skills in realism through dark, shadowy portraits – she also showcased Matisse’s early academic drawings of colorful still-lifes. Compared to other art dealers at the time, especially her fiercest competitor Ambroise Vollard, Weill was extremely innovative in how she selected her pieces and organized her exhibitions; she never once solely displayed the works of known artists who all painted with similar strokes, palettes, and inspiration. Weill always sought individualism and novelty in her clients.

Lynn Gumpert, the director and curator of the Grey Art Museum, has been infatuated with art for her entire life. “I discovered art history when I was an undergraduate and then was able to spend my junior year in Paris where I studied at the Ecole du Louvre and learned about art history,” she explained to me during an interview I conducted with her. “Then I went to graduate school at the University of Michigan, and after three years, I got my M.A. in art history and did one year of course work, until I realized that I really wanted to work with museums.”

When she realized that museums were her true calling, Gumpert moved to New York City, one of the most museum-dense cities in the United States. After working for some time at the Jewish Museum, and then independently for nine years, Gumpert found herself at NYU’s Grey Art Museum.

“I love history, and I love the fact that art history combines history with the study of languages and culture and all the other arts,” Gumpert said. “My favorite part of my job is installing exhibitions. I just love having that direct contact with art and artists, and telling a story through the art and its placement.”

Bringing Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde together was nothing short of a challenge for Gumpert. “It started over 10 years ago when I asked a friend what she was up to,” she recounted, talking about Julie Saul. “She was a graduate of NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts… and ended up being an [art] dealer. She told me that she had discovered a reference to a memoir by an art dealer who was the first to sell works by Picasso and that she had never heard of her and was wondering why.”

After hearing about Weill’s career from Saul, Gumpert read Weill’s memoir. She, like Saul, became obsessed with Weill’s unique story and was surprised to find that it was so overlooked. “The fact that she was the very first to exclusively focus on young emerging artists was fascinating to me because it’s part of a history that I think art historians are now getting more interested in: the history of the art market,” Gumpert said. “What really inspired me was just her passion for art, and the fact that she was self-taught… and that through sheer determination… was able to open and keep her gallery running for 40 years.”

Gumpert and Saul then met Marianne Le Morvan, who had also recently discovered Weill and was looking to bring her story to light. Together, the three of them embarked on a mission to translate Weill’s memoir into English and make her name known.

After a few years, the three women achieved their goal and were starting to discuss the creation of an exhibit. Since the Grey Art Museum was a small institution and required more funding, they chose to collaborate with other museums, specifically the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts where the exhibit will be on view from May 10th to September 7th, 2025 and the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, France, where the exhibit will be on view from October 8th, 2025 to January 26th, 2026.

Putting a collection together to represent Weill was not easy. “We started out thinking that first and foremost we wanted to get paintings that had gone through the gallery,” she explained. “But we soon realized that was very, very costly and challenging because they’re spread all over, and what was more important was telling Berthe’s story.”

Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde represents Weill’s unique artistic taste by juxtaposing Fauvism with Cubism, portraits with abstracts, colors with black and white, and even female artists and male artists. As visitors walk through the small, but packed exhibit, with 110 pieces in total, they cannot help but notice the stark differences between neighboring paintings.

One of my favorite examples of this was two small watercolors placed one on the top of the other. Sandwiched between the end of the exhibit and a room focused on the Dreyfus Affair, these two works are easy to miss. On top is a Jean Veber entitled ‘Yvette Guilbert Singing.’ It is a simple, but emotional painting, where viewers are drawn to the expression and passion of the singer through basic, but strategic black-and-white shading. Beneath it is one of the most colorful paintings from the entire collection, created by Ferdinand-Sigismund Bach. ‘Lole Fuller’ depicts a woman with bright red hair surrounded by a whirlwind of bright teal, royal blue, and yellow, which appears to bounce off of her skin in a trick of the light. The paintings are so striking in their differences: bright versus simple, flat versus dimensional, abstract versus traditional – but this only increases the intrigue of Weill and her “eye,” making it impossible to summarize her taste in one word.

Perhaps the most shocking aspect of Weill’s career that the exhibit covers was her relation to Pablo Picasso. Weill first met the young Spaniard through a Spanish art dealer named Pedro Manach. Upon arriving in Paris in the early 1900’s, Picasso stayed with Manach in Manach’s studio, drawing and sketching new works every day for Manach to sell. Berthe Weill showed great interest in Picasso’s works very early on, purchasing multiple canvases from Manach to sell in her own gallery. Soon enough, Galerie B. Weill was crowded with Picasso’s work and the artist grew tremendously in popularity. Although he would eventually move on to new, bigger galleries to sell his work, he likely would never have gotten that opportunity if Weill hadn’t noticed his talent.

One of my favorite parts of the exhibit was a section that showed only female artists. As a woman in a male dominated field, Weill faced a lot of doubt. Even her parents were reluctant to let her pursue her career, urging her to get married and live a more traditional life when she initially purchased her shop. Extremely conscious of the struggles that women faced in the art world, Weill did everything that she could to uplift female artists in her gallery. In fact, Weill always made sure that each of her shows featured a female artist. The exhibit demonstrates this by including multiple works by Weill’s favorite female artists, such as Émilie Charmy, Suzanna Valadon, and Jacqueline Marval.

Each room in the exhibition leaves you more intrigued to enter the next. As you move from the early Picasso to the Fauvists, from under appreciated female Impressionists to quintessential Cubists, from small sketches to large political advertisements, no single story feels complete. And yet, when put all together, they tell the one complete story of Berthe Weill.

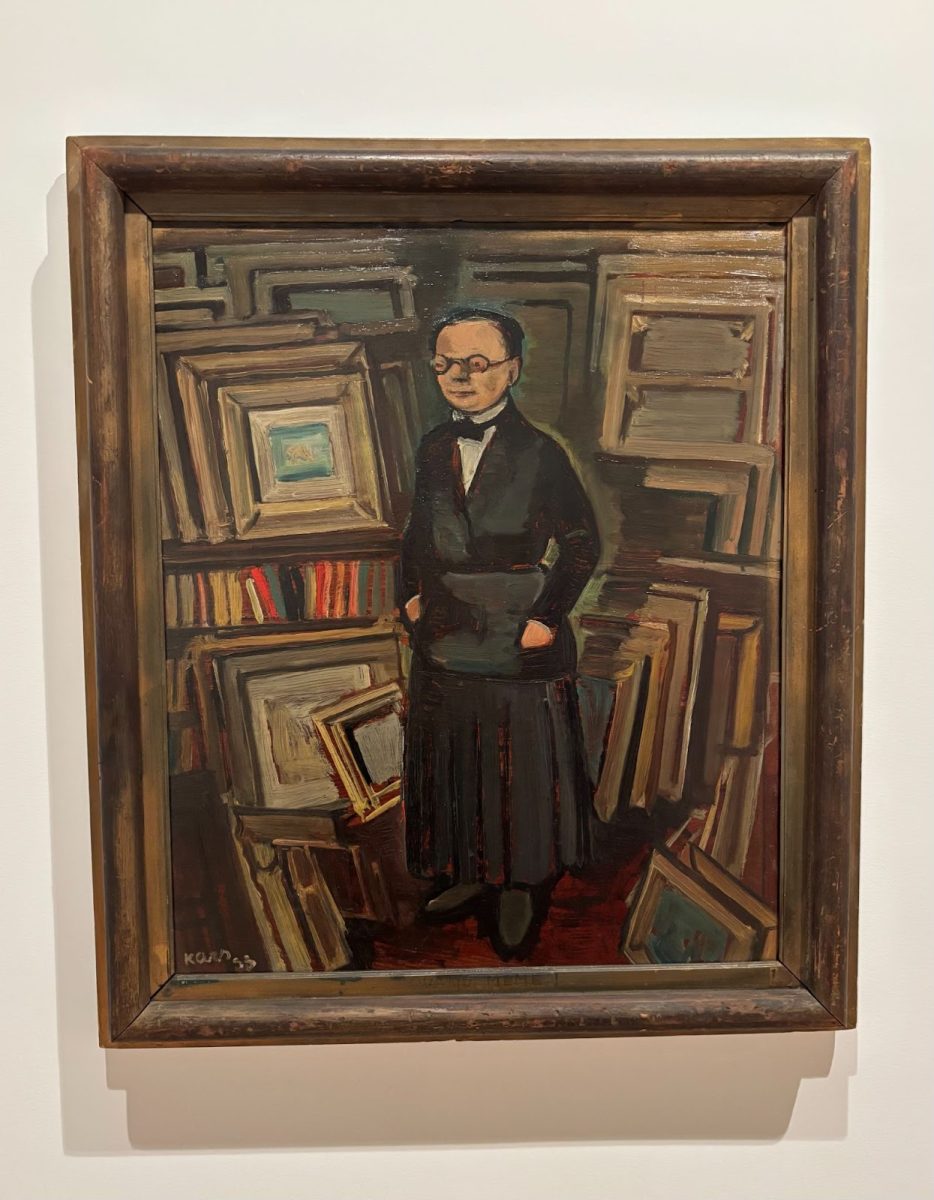

You can’t miss the painting of Weill that is placed at the very beginning of the exhibit, right next to a brief introduction into her career and life. George Kars’ portrait places Weill’s small figure right where she belongs: surrounded by art. Dozens of paintings are laid on top of each other in a messy and disorderly fashion as Weill stands, stern and unamused as ever, right in the middle. It immediately characterizes the art dealer as the businesswoman that she was, driven not just by passion, but by a desire to prove herself.

While the various art pieces in the exhibit are beautiful, what I found more interesting was the timeline that they took you through of Weill’s life as an art dealer. Each room features a couple short paragraphs that describe certain aspects of her career, from her involvement with Cubists to her battle with antisemitism.

Even more details are provided in the large, physical timeline printed onto a wall at the beginning (and also the end – the museum is essentially one big circle) of the exhibit. The timeline includes not only substantial accomplishments in Weill’s artistic career, but also details about her personal life. My favorite part about it was that you were forced to look at it twice by the mere nature of the museum’s architecture. If you take the time to read each of the small paragraphs throughout the exhibit, you might find yourself drawn to the timeline again, astounded by the sheer amount of things that happened during Weill’s life and wanting to see them laid out into one connected timeline.

Despite having received praise from many other art dealers and painters of the early twentieth century, Weill is often excluded from historical accounts of the rise of modern art. Overshadowed by male art dealers of the 20th century like Ambroise Vollard and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Weill struggled to make her name known amongst her well-known male counterparts. More than that, Weill’s commitment to “les Jeunes” – a term she used to describe the young artists she represented – severely limited her clientele. Compared to Vollard, for example, who sold the works of already known and commended artists such as Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh, Weill didn’t seem to have much to offer.

In addition to this, Weill faced a lot of antisemitism all throughout her time as an art dealer, but especially as World War Ⅱ began.

The Dreyfus Affair of 1894 was a political crisis in France where an army captain named Alfred Dreyfus was convicted of treason for selling military secrets to Germany. Most of the public initially supported the charge, especially because Dreyfus was Jewish and antisemitism was common in Europe at this time. However, France eventually became divided over the issue due to suspicions of Dreyfus’ innocence. The debate reached an extreme level when Émile Zola, a journalist of the era, published an article called “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the French newspaper L’Aurore. The long text publicly called out the French army and justice system for the wrongful conviction of Dreyfus, earning Zola his own federal charge for libel. Nevertheless, Zola’s work made the issue even more prevalent amongst French society and people were as enraged as ever on both sides.

Supporters of Dreyfus continued to increase in numbers through 1898, when the government began to grow concerned with the threat to their authority. The case was ultimately reopened in 1906 and Dreyfus was taken out of prison, satisfying the radicals and quelling the rebellion.

Despite being resolved, the event contributed monumentally to growing antisemitism in France – the anti-Dreyfusards were enraged with the decision and continued to discriminate against Jews in their every-day lives, while Dreyfusards feared what the future looked like for Jews and their safety.

Weill was amongst the French Jews who were concerned with the growing antisemitism as they began to experience it more and more often. The exhibit spotlights this period as one of, if not the, most challenging parts of her career by including a framed version of “J’accuse” in the exhibit alongside multiple examples of anti-Jewish propaganda. These additions communicate how the prejudice Jews began to face in this era impacted France in more ways than just politically – yes, it made France more vulnerable to invasion, but it also inadvertently diminished French culture by targeting the people who showcased it.

Antisemitism against Berthe Weill reached its climax in 1941 when she had to close down Galerie B. Weill. World War II had already been going on for two years and the threat to Jews was getting worse and worse with the rapid advancement of the Holocaust. Weill herself had been targeted by the Vichy government and an antisemitic periodical called Le Cahier Jaune (the Yellow Notebook). Edited by André Chaumet and contributed to by popular antisemites like Paul Sézille and René Gérard, Le Cahier Jaune was one of the leading antisemitic publications of Paris. Amidst the various propaganda it published about Jewish politicians and businesses, it also released a piece bashing Weill, criticizing her for a lack of taste and an obsession with money – a common Jewish stereotype. With the article circulating around Paris, Weill no longer felt safe in her gallery, leading her to shut it down and go into hiding.

By the end of the war, Weill was in extremely poor health. Although she had never been responsible with her money, having always been an impulsive spender, she no longer had a steady income from her gallery to live off of.

In 1946, a group of artists and art dealers that had crossed paths with Weill, including Picasso, grouped together to raise money for her. The large auction they organized in her honor ultimately brought Weill into a steady financial position, with 1.5 million Francs (around 250,000 U.S. dollars) to live off of for the rest of her life.

Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde is more than just an art exhibit– it leaves us thinking about what it meant to be an independent, working Jewish woman in pre-war France. If not for Berthe Weill, it is likely that some of our favorite modern artists of all time would not have been discovered, and we would not have witnessed their unique talents. She is responsible for bringing the Fauvists together, introducing Picasso to the professional art world, creating the only Amedeo Modigliani exhibition during his lifetime, and more.

While Berthe Weill might have “slipped through the cracks of art history,” as Gumpert said, Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde is one large step towards changing that paradigm.

“What really inspired me was just her passion for art, and the fact that she was self-taught…and that through sheer determination…was able to open and keep her gallery running for 40 years,” said Lynn Gumpert, the director and curator of the Grey Art Museum.