As I stepped off the 3 train and entered the Jewish Chassidic neighborhood of Crown Heights, Brooklyn, I felt welcomed by a warm breeze. All around me were signs of Jewish identity; the streets were full of people dressed in religious clothing, with the fringes of tzitzits and the fur of shtreimels catching my eye, and I stopped by stores selling Jewish food, such as matzah, as well as bookstores full of Jewish literature.

I continued to walk through the area, admiring the beauty of the neighborhood on a sunny Saturday afternoon.

After some time, a small art gallery, hidden in between a driveway and a clothing store, caught my eye. Across the door read the name “Chassidic Art Institute,” and as I peered through the window, I could see stacks and stacks of paintings, each one of them depicting an individual Jewish experience. In just a tiny space, there was an amazing collection of art lining the walls, racked up on desks, and even on the floor.

(Sophia Birman)

Curiously, I entered the gallery. I was immediately encapsulated by the art – the technique, the realism, the beauty, and, most importantly, the message. This was one of the first, if not the only, times I saw Jewish art being truly recognized and celebrated. After centuries of pushback, I felt that Jewish identity was finally being shown to the world, pridefully out in the open.

I began conversing with the employee who was monitoring the gallery. What began as a short inquiry quickly led into a fascinating conversation about not only the paintings at the gallery but also the history of Jewish art as a whole.

I left the conversation captivated and eager to learn more. Over the next couple of weeks, I began researching the history of Jewish art, and what I found fascinated me.

The Evolution of Jewish Art

While a few pieces of ancient Jewish art have been recovered, relative to other ethnic and religious communities, collections are scarce. Indeed, several factors have contributed to the Jewish community’s delay in entering the realm of artwork.

For one, Jewish communities have historically regarded art as a sin. The prohibition of images depicting religious entities, stemming from the Second Commandment in the Hebrew Bible, was often misinterpreted as a broader forbiddance to visual art as a whole.

However, even the Jewish individuals who didn’t believe in this interpretation of the Second Commandment still had trouble producing and engaging with art. The Jews’ diasporic lifestyle in ancient times made it extremely difficult to transport art, and Jews were heavily encouraged to spend their free time studying the Torah, rather than producing creative works. Thus, the value of art was severely diminished and lacked cultural importance at the time.

As time went on, thankfully, old values began to fade away and Jewish art began to develop. Appearing first as mosaics, scrolls, and murals, Jewish art became prevalent during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The influence of Islamic rule is evident in the artwork made during this time; for example, manuscripts of Hebrew texts from the Middle Ages are often supplemented with intricate designs influenced by Islamic art techniques. One notable instance of this is seen in early Hebrew Bibles which contain geometric and arabesque designs, Islamic motifs, such as gilded elements, and lettering styles adapted from Islamic art.

Another embodiment of this is found in Haggadahs. A Haggadah is a book, made up of art and text, used during the Passover Seder that depicts the Biblical story of the holiday. Haggadahs made in the Middle Ages often include aspects of Islamic culture – for instance, the Golden Haggadah includes geometric patterns found in Islamic art.

Unfortunately, these advancements in Jewish art were expected to come to a halt when European Jews were forced into ghettos during the Middle Ages. However, Jewish artists persisted – they began painting in secret, using whatever materials they could get their hands on. They painted on walls, scraps of paper, and the backs of old books. Despite tough times, they found joy in this medium of expression.

Their paintings were used to educate people about Judaism, serving as a means of resistance.

With the onset of the Enlightenment in Western Europe, Jewish artists were finally able to leave the ghetto and develop a strong community. They created and showcased artwork depicting their relationship with their Jewish identities, and the world of art began to accept them.

Concurrently, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the Haskalah movement began to develop in Eastern Europe before spreading to Western Europe. It was a Jewish cultural movement that encouraged secular study, literature, and most importantly, art. It gave a new sense of freedom for Jews, opening up avenues of expression.

Nevertheless, this cultural progress was defenseless in the face of oppressive policies. Jewish art was often censored due to a lack of religious freedom in Europe; Jews were not allowed to study art in the majority of European countries, and in some nations, they were persecuted if they were caught making artwork. They were considered to have “too much talent,” which threatened the livelihoods of local artists.

Not all Jewish artists painted religious themes, yet they were censored regardless. Even landscapes and portraits were not allowed, as they were seen as a challenge to the Christian monopoly over the European art industry. Jews could only exhibit their work when they traveled outside of Europe, if that.

In Eastern Europe, the situation was increasingly dire. Jewish individuals were restricted to living in designated areas, where life was bleak and opportunities were scarce.

At the end of the 19th century, the Russian Empire became even more oppressive towards its Jewish population, and as anti-Jewish pogroms escalated, Jews were left without a voice or an outlet for artistic expression.

Only in the 20th century did Jewish art finally begin to flourish. The Educational Alliance, a settlement house on New York’s own Lower East Side, hosted one of the first art classes in history specifically targeted to Jewish artists.

Since then, Jews have continued to use art as a medium of expression, a coping mechanism, and a form of resistance. Prisoners during the Holocaust utilized art as an expression of nostalgia as well as a form of self-preservation. Their struggles were also reflected in many Jewish paintings in the years following the Holocaust.

As a whole, art has helped Jewish individuals survive the worst of times and enjoy the best of times.

It is because of this that I can now appreciate the abundance of Jewish art found in the Chassidic Art Institute.

The Chassidic Art Institute

The Chassidic Art Institute, located at 375 Kingston Avenue in Brooklyn, New York, is a small yet packed art gallery containing hundreds of paintings depicting Chassidic Judaism – an Orthodox religious movement in Judaism.

The gallery was founded in 1977 and has since then promoted Jewish art as well as the artists themselves, linking current experiences to Jewish history.

I had the pleasure of interviewing one of the founders of the gallery. He explained how growing up, he was taught the importance of Jewish art, being the son of an art collector and eventually, an artist himself.

Yet, he felt that he was constantly denied a space for showcasing his art. He explained the issues he constantly encountered, stating that “Jewish art has been neglected for centuries…We are constantly denied having our work shown in Museums because we are Jewish.” Thus, with the help of four friends who were also Jewish artists, he created the Chassidic Art Institute.

“We needed to do something for Jewish artists,” he explained. 47 years later, this project has sprung up into a successful art gallery, hosting hundreds of beautiful paintings and providing a platform for both established and emerging artists.

Through thematic exhibitions – addressing topics such as diaspora identity, social justice, and interfaith dialogue – the gallery additionally serves as a catalyst for meaningful conversations and reflections within the broader community.

As I continued exploring the gallery, I was fascinated.

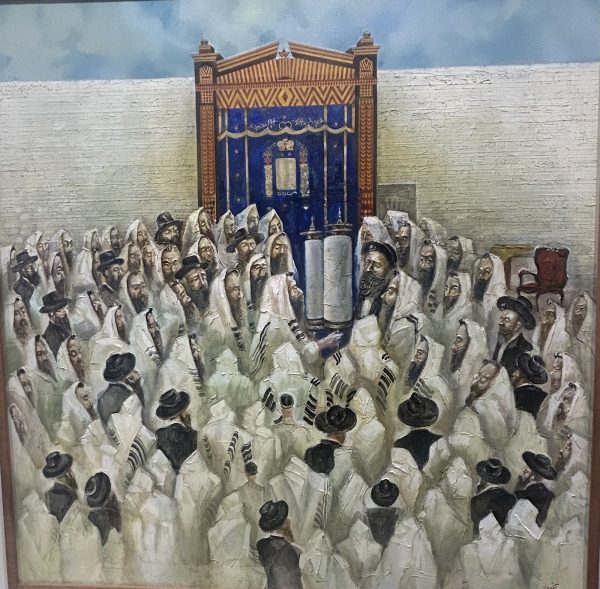

One piece that stood out to me in particular was a painting entitled ‘770’, created by Michael Gleizer, a Ukrainian-born Jewish artist who resides in New York. The painting depicts Simchat Torah, a Jewish holiday during which festive Torah readings are held. It is a joyful day, made up of singing, dancing, and congregating, ultimately celebrating the Jewish text and prompting reflection on what the Torah means to each member of a community.

The painting meaningfully and beautifully depicts this experience, showcasing a group of men gathered together around a scroll of the Torah, each reflecting to themselves. The bright blue sky in the background highlights the jubilance of the holiday, and as each man is wearing similar religious wear, the communal nature of the day is underscored.

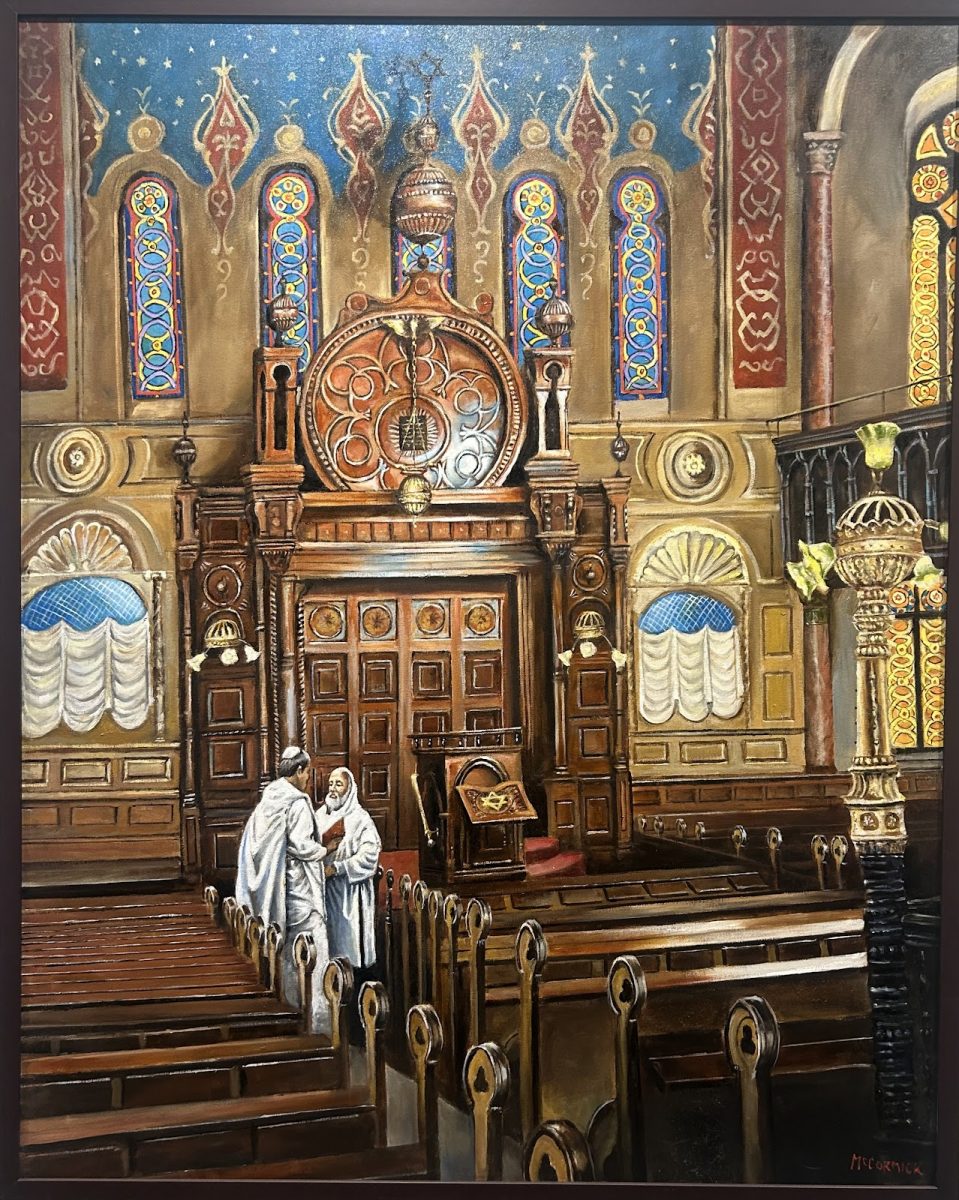

Beyond this one piece, each and every artwork in the gallery portrayed an independent aspect of Jewish culture – whether that was Rabbinical authority, religious wear, the Torah, religious rituals, or the architecture of synagogues. In each painted face, joy, celebration, culture, suffering, and values radiated through. The paintings, whether they depicted one person or 100 people, were symbolic of a shared experience felt by millions of Jews worldwide.

The Jewish art in the gallery, similar to the religion and culture itself, had a recurring theme of suffering. This modern art often depicts struggles between the past and the present, traditions and modernity, and community and individualism. The art conveyed the internal battles of every Jewish individual, seeking to discover meaning and identity in this art.

Knowing how long it took to get here – to this point of religious freedom– made the experience even more monumental. What I was looking at was not just a painting that took a month or a year to complete, but rather the product of centuries of persecution, resistance, expression, perseverance, and celebration.

The Influence of Jewish Art in the Modern Day

In the present day, Jewish art continues to develop, both inside and outside the Chassidic Art Institute.

Many Jewish artists have begun using bright colors in their paintings to bring life to their pieces, a significant shift from the gloomy colors used in the post-World War II time to a new era of religious freedom.

Regardless of the specific artist, or the specific purpose of a painting, Jewish art as a whole is vital to the advancement of modern art. Jewish art has thus far had a major influence on the development of abstract expressionism, a type of abstract art that values authenticity and defies typical norms, as Jewish artists were the main contributors to this movement.

Furthermore, the work of Jewish artists is a crucial consideration when exploring the larger topic of how religion is expressed in the modern world. Rooted in centuries of tradition, yet continually evolving to reflect contemporary realities, Jewish art serves as a testament to the resilience, creativity, and diversity of the Jewish people.

Whether it is through exploring contemporary social issues, preserving historical narratives, or nurturing emerging talent, the Chassidic Art Institute remains steadfast in its mission to cultivate a vibrant and inclusive artistic community, ensuring that the legacy of Jewish art endures as a source of inspiration and cultural enrichment for generations to come. If you ever find yourself with free time on your hands, I highly recommend paying a visit to the gallery – I guarantee you will end the day with fresh knowledge, insight, and understanding.

Beyond this one piece, each and every artwork in the gallery portrayed an independent aspect of Jewish culture – whether that was Rabbinical authority, religious wear, the Torah, religious rituals, or the architecture of synagogues. In each painted face, joy, celebration, culture, suffering, and values radiated through. The paintings, whether they depicted one person or 100 people, were symbolic of a shared experience felt by millions of Jews worldwide.