Cookie Science

How chemistry might be behind your favorite sweet treats, and how that can change the way you bake.

The non-vegan sugar cookies were soft and slightly chewy.

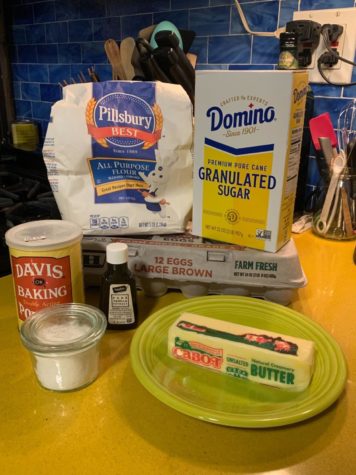

Flour, baking powder, sugar, butter, eggs, and salt. These six ingredients are the foundation of many recipes, including breads, cakes, cookies, and pies. But how exactly do these specific elements come together in order to produce such delicious results?

To find out, I decided to head to the kitchen and start baking. And when looking for recipes, I wanted to find only those that included these six foundational ingredients, so I settled on a basic sugar cookie recipe from the Bigger Bolder Baking blog. However, I thought it would be fun to add a little twist to my endeavor by making half of the batch vegan.

Dietary vegans, individuals who do not consume animal products such as meat and dairy, are increasing in number across the country, with around 9.6 million Americans now following a plant-based lifestyle. Some choose to eschew these products for their health, as vegan diets are associated with a lower risk of heart disease, while others cite environmental or ethical concerns for their choice.

For this project, I needed to delve into the world of vegan substitutions, but to adequately ‘veganize’ the recipe I was using, a little bit of research into food science was required first.

I started with the dry ingredients. Wheat flour provides a baked good’s structure, the stage upon which other ingredients may act. Hydrated flour proteins interact to produce gluten, which forms an elastic network that stretches and allows baked goods to retain their shape when rising.

That rising, or leavening process, is essential to baking, and is caused by leavening agents, such as baking powder and baking soda. When added to the mixture, the resulting chemical reaction produces carbon dioxide, which is subsequently trapped by the dough. However, this chemical leavening is not the only way to help a baked good rise in the oven. Air and steam can also be used as physical leavening agents, since they increase the volume of the dough.

The next ingredient is made from the molecule sucrose — sugar — and has important purposes besides adding sweetness to the baked good. When heated, it can caramelize, which results in the soft toasty brown color that adorns many treats from cookies to pie crusts.

In addition, sugar helps retain moisture thanks to its hygroscopic properties. This slows the development of gluten chains, which tenderizes the baked good. Likewise, it prevents staling and increases the product’s shelf-life. Sugar’s moisture-retention ability also allows the ingredient to act as a physical leavening agent by creating steam when heated, as the water retained by the sugar will evaporate which causes the dough to rise.

The last dry ingredient, and probably the most overlooked aspect in most baking recipes, is salt. Salt not only adds savoriness to balance the sweetness of the dessert, but it also has the same hygroscopic properties as sugar, helping baked goods last longer.

Moving onto the wet ingredients, there is butter, a solid fat, which has three main roles in the baking process. First, it adds a rich flavor, which is what differentiates the flavor of a brioche (made with butter) from a baguette (made without butter).

It also tenderizes the final product: a brioche is soft, while a baguette is crusty. This is due to butter’s ‘shortening’ effect on gluten chains formed by the flour. Butter can also act as a leavening agent, since it is around 18% water.

But to even have a cohesive dough or batter to bake, there also needs to be a binding agent. Eggs act as such by holding different components together, and their gel-like properties solidify the structure of a baked good when heated. They can also act as leavening agents, since eggs have a high water content.

Now that I had a basic understanding of what each ingredient was doing in the recipe, I was able to start experimenting with vegan substitutions. Laura Pong ‘22, an avid baker and a vegan, reminded me that “mimicking not only flavor and texture, but also chemical reactions is ultimately the end goal for all substitutes.” This was why I had to proceed with caution.

When I was researching how to veganize the sugar cookie recipe I was using, I was surprised to discover that not all kinds of sugar are vegan. Some refined sugar, especially the typical granulated white sugar you would use in baking, has been processed with bone char. According to PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), “bone char — often referred to as natural carbon — is widely used by the sugar industry as a decolorizing filter.” So for my vegan sugar cookies I used stevia, a natural sweetener derived from stevia leaves, and a simple enough substitution as far as chemical reactions were concerned.

Butter and eggs were more precarious. Laura recommended that I switch out my dairy butter with a non-dairy alternative, like Earth Balance. She argued that “vegan butter is the simplest substitution for regular butter,” but added that for those who may have trouble finding some at the local grocery store, “You can just use a mix of vegetable oil and a little bit of liquid, since you will end up with a fat source and something to dissolve your sugar with.”

I read countless articles about the best possible egg substitutes. Some were proponents of using ground flaxseeds or chia seeds mixed with water, but Laura warned that “adding a chia seed egg or a flax egg to sugar cookies may change the color and add a nuttier flavor.” She instead told me to try adding some unsweetened applesauce or mashed banana.

I surfaced from my research, armed with vegan butter and egg-replacements, ready to bake.

For the non-vegan cookies, I creamed together my butter and sugar before adding an egg and some vanilla extract for flavor. The wet ingredients for my regular cookies looked smooth and were tinted slightly yellow, likely from the egg. Afterwards, I added vegan butter, stevia, and applesauce to my vegan cookies.

The butter and sugar substitute had a similar texture, but the applesauce was less viscous than an egg. After adding the dry ingredients, which were the same for both batches, I found that my vegan dough was both less yellow and crumbled more easily. I suspect that I should have added some more applesauce. I used a standard conversion, ¼ cup of applesauce for one egg, but my flour content was slightly too high for that to suffice.

I added some sprinkles to the non-vegan cookies for a pop of color and to differentiate my two batches (sprinkles often contain shellac which is derived from animal products). The end result was interesting. As I suspected, the vegan cookies came out slightly cake-ier and just a tad dry, so I definitely plan on using more egg substitute the next time. I could also taste a slight applesauce-y flavor. The regular batch was similarly cakey, but not nearly as dense as the vegan ones.

Although not quite perfect mirrors of each other, I would still consider my experiment to be a success. (I got to eat cookies and say it was for science!)

When I asked Laura about other ways to veganize a cookie recipe, she said, “It’s helpful to just look at vegan cookie recipes, look how they substitute ingredients, and be willing to experiment.”

That last part really stuck with me. Baking is a highly specific process, and not simply a collection random ingredients tossed together and throw into the oven — great care goes into selecting the flavors and finding the perfect ratios of each component, from flour to butter.

Laura Pong echoed the sentiment. “I feel like I’ve learned a lot more about baking since going vegan. It’s also a fun challenge to see how I can make a baked good just as good as its non-vegan alternative.” So I guess I’m back to the kitchen to go try another recipe.

Baking is a highly specific process, and not simply a collection of random ingredients tossed together and throw into the oven — great care goes into selecting the flavors and finding the perfect ratios of each component, from flour to butter.

Meriel Crowley-Wang is an Editorial Editor for ‘The Science Survey.' She enjoys the logical way in which journalistic writing presents itself to the...