Unwelcome Awards

Across the music industry, there are cases of implicit racism that often go unnoticed by the public.

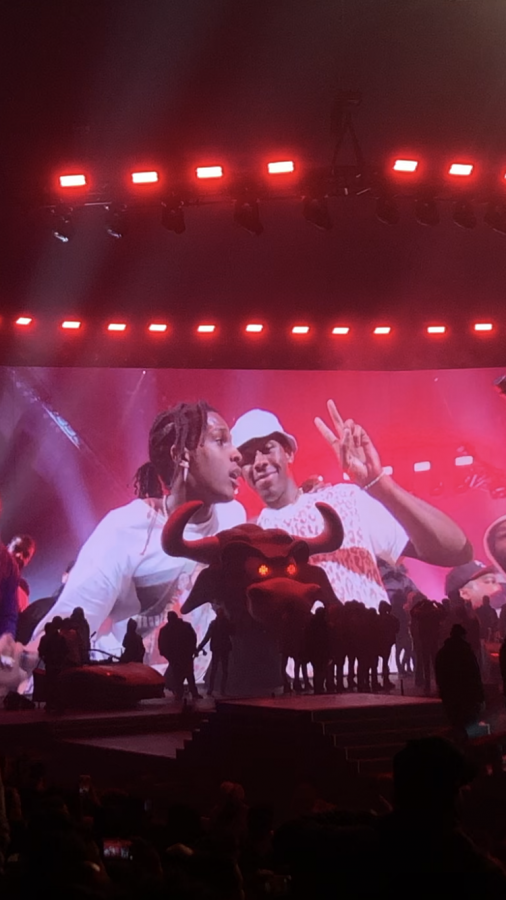

Tyler the Creator (right) makes a guest appearance at Yams Day 2020.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, music’s definition is: “vocal or instrumental sounds (or both) combined in such a way as to produce beauty of form, harmony, and expression of emotion.” Yet this doesn’t adequately encompass the full breadth of music and its hundreds of genres, or its historical context. Artists across the industry create music for many reasons, such as testaments of love, feelings of longing and loss, and for celebration. There is also a rich history of creating music in response to oppressive systems, as an outlet to escape reality and convey feelings of anger and hope. The genres of rap and hip-hop both emerged right here in New York City, created by marginalized youth in response to racial inequality.

The unheard struggles constantly faced by the Black community are publicly shared through rappers’ music, giving the underrepresented group a voice. However, the commercialization of rap frequently hides the oppressive historical context from which it emerged, and most people are oblivious to rap’s original community and purpose as its popularity continues to grow.

African-American rapper Kendrick Lamar released his album, To Pimp a Butterfly in 2015, in which he incorporates African-American culture and allusions to the constant discrimination experienced by people of color. He indirectly references black history in many of his lyrics, and his songs share his insight on white privilege with his community. In his song ‘King Kunta,’ he says, “…where you when I was walkin’? Now I run the game, got the whole world talkin.’ King Kunta, everybody wanna cut the legs off him. Kunta, black man taking no losses…” where Lamar refers to himself as “King Kunta,” an assertion to American author Alex Haley’s character Kunta Kinte in his novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family. Haley based Kunta Kinte off of his enslaved Gambian ancestor born in 1750, whose feet were cut off upon attempting to escape bondage.

Ms. Wilhelm, organizer of the Modern Music Club, said, “There is always prejudice and bias against artists of color.”

Rap lyrics often come across as violent or crude when taken literally. However, these lyrics typically stem from a genuine sentiment, expressing the issues of racial inequality experienced by the African-American community in both the past and present. Ms. Wilhelm, an English teacher and organizer of the Modern Music Club at Bronx Science said, “Hip-Hop is the collective music of underserved and undervalued cultures and populations of people… who have been historically and systematically oppressed for decades and centuries.” The legacy of slavery and segregation shapes the African-American peoples’ identity even in modern times, and music helps to convey their ongoing social struggle with the past in a form of art.

However, many African-American artists are wrongfully classified as rappers or put into the category of hip-hop solely based on their race and the social norms generated by the music industry. Bryce Zampty-Hicks ’22 responded to the stereotypes by saying, “The Academy and the music industry as a whole always tries to put black people in the category of Rap/Hip-Hop or R&B.” In the recent 2020 Grammy awards ceremony, institutional racism was evident in many of their choices. Tyler the Creator’s recently released album Igor won rap album of the year and his album Flower Boy was previously nominated in 2018 for the same division. Tyler’s music has changed over time, as his musical output shifted in 2015 into a wider variety of genres and a less confined style. His more recent albums make his transition even more apparent as his songs become increasingly diverse, Igor being a medley of both punk and pop with fleeting rap verses. His nomination and win for the rap category reveal the Recording Academy’s implicit racism in their choices, as they often categorize artists of color separately into genres like rap and hip-hop and grant the other awards to Caucasian artists. Tyler responded to the controversy on his win and the racial divide by saying, “On one side I’m very grateful that what I made can be acknowledged in a world like this; but also, it sucks that whenever we—and I mean guys that look like me—do anything that’s genre-bending or anything, they put it in a rap or urban category.” Tyler’s mixed feelings of gratitude and caution reveal how institutional racism often goes unnoticed by the public.

Elizabeth Obrusnik ’22 said, “I think racism in the music industry is still very present, but more subtle.”

Elizabeth Obrusnik ’22 said, “Through acts of denying artists of color access to certain live music venues, or giving a well-deserved award not to the artist of color, but a white one instead, some underlying prejudice is apparent even today.” Diversity has long been identified as an issue in the music industry, and the lack of non-Caucasian representation in each genre shows just how biased the system has become. Ms. Wilhelm said, “If you look at culturally, historically and socially influential shows like The Oscars and The Grammys, there have been many years of entertainers protesting and criticizing The Academies for not including diverse award winners, nominees, and presenters in their shows, resulting in the new initiative to diversify these aspects of American culture and include more international and diverse backgrounds in their shows.” The subtle racial discrimination that often takes place in the music industry should be recognized for what it is. Upon looking back on the dictionary definition of music, a more accurate interpretation could be a medium of expression in which artists of all backgrounds respond to the issues in society and share aspects of their cultures and identities as lyrics and melodies.

“Through acts of denying artists of color access to certain live music venues, or giving a well-deserved award not to the artist of color, but a white one instead, some underlying prejudice is apparent even today,” said Elizabeth Obrusnik ’22.

Ellora Klein is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey.' She enjoys exploring different perspectives through writing, editing, and reading. Ellora chose...

Victoria Diaz is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey'. She believes that journalism is important in its ability to share ideas and knowledge with...