Austrian artist Egon Schiele was obsessed with death. Ironically, his life began and ended with tragic loss, first with the death of his beloved father, a railroad station master who died of syphilis when Schiele was 14, and then with his own premature passing at the age of 28. A new exhibit at the Neue Galerie in Manhattan, ‘Egon Schiele: Living Landscapes,’ digs deeply into this all encompassing fascination with a series of emotionally charged landscapes and villagescapes. Spanning throughout the entirety of his short life, these pieces feel almost more intimate than his best-known nude drawings, acquainting viewers with a more underrated aspect of his artistic cannon and carefully unpeeling the inner workings of the man behind the canvas.

Schiele started painting at 16 years old following his father’s death, and his emotional turmoil at the time is represented both on the canvas and through the writings that he left behind. He left home to attend the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts but criticized the city and its inhabitants, noting in one letter “everybody is envious of me and deceitful.” Dreary, fog-laden paintings of other urban areas from this period mirror his distaste.

The Neue exhibition is mostly chronological, and the first room integrates both photos displaying Schiele and his family, as well as his earliest works from his teenage years. Klosterneuburg in the Fog, completed when Schiele was 17, highlights a snowy, scorched patch of earth with the outline of cityscape in the background, while Meadow with Villages in Background 1 similarly depicts snow speckled earth with foggy background outlines. Both pieces are a far cry from Schiele’s developed oeuvre, but they provide the earliest portrait of his thoughts at the time and his affection towards the natural world that later takes center stage.

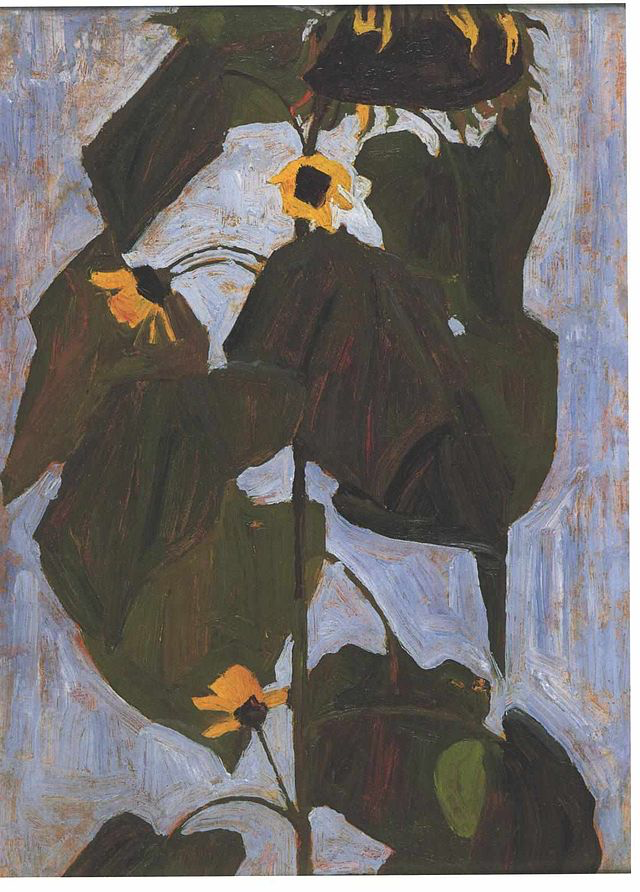

Schiele’s art progressed quickly after famed Austrian artist Gustav Klimt (who Schiele often referred to as his personal hero) took him under his wing. Under Klimt’s guidance, Schiele produced one of the exhibition’s highlights, and my personal favorite, Sunflower I. In this work, a single wilted sunflower is brought into sharp focus, its stark green and faded yellow hues set against a soft lilac background. The flower embodies death itself: its drooping, gray-tinged leaves, withered yellow petals, and bent stem sinking toward the earth. It is both captivating and unsettling — it is impossible to look away from.

As Schiele matured, he moved away from the vibrant colors of his earlier works, embracing a palette dominated by darker hues — deep reds, browns, blacks, and grays — that swirl together to form atmospheric autumnal landscapes. Experimenting with various styles, he eventually developed a distinctive technique that seamlessly blends elements of realism and cubism. This is particularly evident in works such as Stein on the Danube, Seen From the South (Large), completed at the age of 23. In this piece, a delicately swirling sky seems to fold in on itself, its muted green and tan tones arching over and framing the serene, medieval town below. Just like Sunflower I, Stein on the Danube, Seen from South (Large) has two dueling messages that compete for dominance: historical preservation and innovative modernism. The sky almost appears to be geological layers of the earth, and the earthy color palette gives the impression of a landscape caught between life and decay, as if the land itself is both eroding and enduring. This duality mirrors Schiele’s own perception — where beauty and decay are inseparably intertwined.

Though the exhibition highlights Schiele’s landscapes, a few of his best known nude and portrait pieces are also included. The figures in these works — brittle, emaciated, and often bloodshot — are rendered with apparent vulnerability. And yet, despite — or perhaps because of — their grotesque qualities, these figures possess an undeniable allure. They demand the viewer’s attention, forcing an intimate confrontation with the tension between beauty and decay, life and death.

One particularly brilliant work, Self-Portrait with Peacock Waistcoat, Standing, depicts Schiele himself, sporting a confident smirk, with a hint of arrogant superiority. Dressed to the nines in a collared shirt, a rich blue coat, and what seems to be an angel halo encircling his head, Schiele appears every bit the smooth city-dwelling aristocrat he seems to so vehemently detest. Yet, beneath this polished exterior lies a subtle irony: Schiele’s exaggerated pose and expression feel almost performative, as if he is mocking the societal conventions he outwardly embodies.

But Schiele’s primary gift, as he put it, was manifesting the spirit of life onto canvas. “I can speak with all living creatures, even with plants and stones; speak, speak directly into their face, into their essence,” he once wrote.

In one such piece, River Landscape With Two Trees, a barren landscape blankets the canvas, complete with two leafless trees in the foreground. On the surface, it appears to be another depiction of hostile decay, but a closer look reveals a different story. A rising sun peeks out of the background and an array of budding magenta and white flowers dot the barren earth — they represent hints of spring to come and a promise of hope even amidst the hostility.

In another work, Wilted Sunflowers (Autumn Sun II), a close up of a patch of blue and yellow wilting flowers sits beneath a waning sun. While one tangle of decaying sunflowers is in focus, a pile of flowers in the background appear healthy and sprite, signifying a new era.

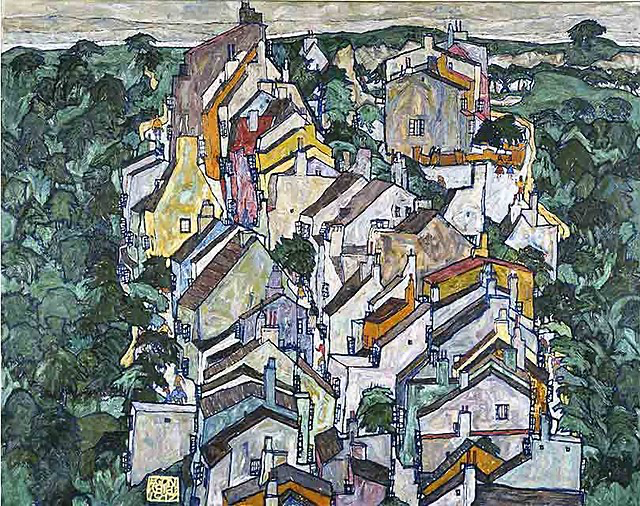

Color was clearly important to Egon Schiele. He uses color to convey death and rebirth, as a symbol of his shift from youthful naivete to adult realism to show his dissatisfaction with urban dwelling. But interesting enough, the title image of the Neue exhibit and arguably the most famous, Town among the Greenery (The Old City III),is eye-poppingly bright. The painting depicts a small village nestled against vibrant greenery and almost seems like a page from a storybook, a compilation of quaint blue, yellow, orange, red and pink houses tightly packed against one another. After so long painting desolate towns and quiet landscapes, Town among the Greenery (The Old City III) appears to be the representation of Schiele’s dream fantasy, a brief escape into a world that is not permeated by human concern.

Yet it is the clear outlier in the exhibit. The vast majority of Schiele’s paintings are dark and weighty, absent the rose colored glasses worn by many of the era’s other premier painters. They are twisty and fascinating, dark and detailed, but above all, his pieces are real. Schiele clearly didn’t believe in sugar coating. He had experienced deep loss, and knew of the harsh, unforgiving landscape that waited outside the door. Instead, he drew the world as it was, as he knew it to be — an endless, perpetual cycle of life and death.

The vast majority of Schiele’s paintings are dark and weighty, absent the rose colored glasses worn by many of the era’s other premier painters. They are twisty and fascinating, dark and detailed, but above all, his pieces are real.