It is Spring 1911, and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan has just opened its doors to reveal an exceedingly peculiar exhibit. On the walls were neatly hung drawings and watercolor paintings, 83 of them, all created by an up-and-coming artist from Paris. These works directly contradicted the well-known style of Realism and strayed far from the newly popular movement of Fauvism. The paintings are sharp and jarring yet smooth and rounded. Though they have a real, tangible subject, the art uses only the most basic lines and shapes to present that subject. The artist is Picasso, and the era of Cubism is just beginning.

Picasso hasn’t always been a household name. In 1910, he was almost completely unheard of in America, even in New York, where the art culture had been experimental and radical for over a century. The Little Galleries of the Photo- Secession owned by Alfred Stieglitz, later renamed Gallery 291, held the first exhibit of Picasso’s work in America. The exhibit, although covered by local press, received little attention, and only two drawings were sold. Stieglitz himself purchased one, and Hamilton Field bought the other.

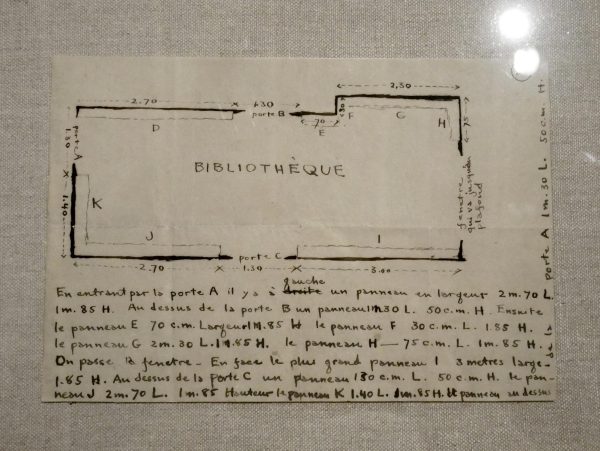

Hamilton Field was an artist, critic, and gallerist who became fascinated with Picasso’s work about a year prior to viewing the Gallery 291 exhibit. Field had been hoping to find an artist willing to undertake the project of decorating his Brooklyn apartment, and with Picasso, he hit gold. Field sent a letter, delivered by a mutual friend, to Picasso in Spain, 1910, a year before the Gallery 291 exhibit. The letter detailed a request for a commission, the dimensions of Field’s library room in his brownstone in Brooklyn Heights, and a grant of permission to use creative liberty, reading “Do whatever you think best suited to the room.” Picasso kept this letter for his entire life.

(Frances Auth)

Picasso spent close to a decade working on Field’s commission. The commission consisted of six wall panels, each over six feet tall and with varying widths. Field supplied Picasso with one of his first opportunities to experiment with larger-scale artworks, and Picasso went about this in a few ways. For some panels, he sketched his ideas and scaled them up, and for others, such as Nude Woman (1910), he started painting on a canvas-sized panel and continued to expand the painting from the bottom.

These pieces were shipped to Field’s apartament and stayed undiscovered by historians for many decades, until coming to light after Picasso’s passing. Historians who found large Picasso panels realized that the panels matched Field’s specifications, and linked the artworks with Field’s commission. They are now exhibited at a Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition, Picasso: A Cubist Commission in Brooklyn, open from September 14th, 2023 until January 14th, 2024.

When entering the exhibit, the first thing that visitors notice is the darkness of the room. The exhibit is dimly lit, providing a gloomy atmosphere and mood for the viewers. Anne Pratt, a local New Yorker visiting the exhibit, commented that the artwork in the exhibit “seems a little less colorful. It’s very black and white, and it feels very dark.” This highly contrasts later Picasso works, which are well known for their bright, vivid colors. Not only is the room dark, but the panels themselves are dark, textured, and full of layered geometric shapes. The most commonly used colors are gray, black, and different shades of brown. The paintings have depth, but they do not achieve this through colored shadows of any kind.

Some panels, such as Still Life on a Piano (1911-12), are easily identifiable, with music notes and piano keys visible in the painting. Still Life on a Piano is particularly captivating because of the deep and beautiful way that it presents as art. These panels were set to be hung in the library of Field’s home and their mood gives light to the dark side of creativity. The chaotic perspective and dark colors evoke images of a struggling musician, late nights, and diligent labor. This work makes use of the most vibrant colors of all in the room, and although the splashes of white and green are not very bright in comparison to other Picasso works over the years, they are eye-catching in the dimly lit room.

Other panels, like Man with a Mandolin (1911) and Man with a Guitar (1913), are much more abstract, with the titles of the paintings being necessary in order to identify the subjects. These works hang side by side with identical dimensions and similar color schemes. There are subtle curves in the lower half of Man with a Mandolin that give the illusion of an instrument of some kind. In comparison to the other works in the exhibit, these are made mostly of light colors, such as beige, brown, and light gray. Both pieces have a contrast with an obviously darker top half and lighter bottom, making them feel almost off-balance.

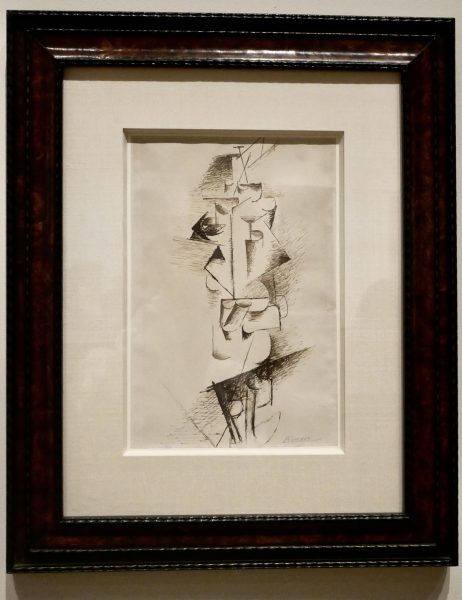

One of the most intriguing parts of this exhibit is the incorporation of sketches and drawings. Many of the framed pieces on the walls of the Metropolitan Museum exhibit are barely finished sketches which resemble some of the completed panels. The inclusion of these drawings in the final exhibit is one of the aspects that makes it feel personal. The commission was created for Fields’ private home, and it was curated to feel private and induce self-reflective thoughts. The drawings mostly consist of earlier versions of Nude Woman (1910) and are made of ink on white paper, hung on two sides of the room.

These sketches, one in particular called Standing Female Nude (1910), are particularly compelling because they portray the subject very clearly, despite being abstract. Through the curvature of the lines, the grouping of shapes going vertically through the center of the pages and the vertical lines drawing the eyes downward, the sketches clearly portray a standing woman.

This piece highlights the juxtaposition between abstract and realistic art and Picasso’s ability to bridge that gap through the wide variety of styles portrayed in his artwork. In the era that Picasso lived, when he was popular for his abstract Cubism in France and just beginning to emerge in America, the piece Nude Woman could have been an attempt to appeal to both the Realist and Abstract art appreciators. This not only helped him gain popularity in America but provided his French fans with a new perspective of his art.

The only sketch in the exhibit that is not an underdeveloped version of Nude Woman is an ink drawing on dark orange paper named Study of a Nude Woman (1905-6). This drawing is very simple. It directly juxtaposes the rest of the artwork, drawings, and finished panels, due to its simplicity and non-Cubist style. This piece was the one that Field bought from the 1911 Stieglitz gallery, hoping to keep and display this piece to show the evolution of Picasso’s style. The drawing serves this purpose well, as it stands out in the room and provides a grounding aspect to the abstract exhibit.

After the completion of his commission for Field, Picasso’s art had evolved. Despite the reflection of early Cubism throughout the commission, Picasso had changed his art style over the near decade he spent on it. By 1915, near the end of his time working for Field, Alfred Stieglitz held a second exhibition in Gallery 291, this time presenting work by both Picasso and Georges Braque, the artist who developed Analytical Cubism alongside Picasso. This exhibit was far more popular and successful than the first. Picasso’s unique style and branches of Cubism had integrated themselves into New York.

Picasso went from being one of the “Wild Beasts of Paris” (as described by the New York journal Architectural Record in the early 1900s) to one of the most popular and appreciated artists in the world. After the Metropolitan Museum of Art turned down his offer to purchase all of his pieces from the first Little Galleries of the Photo- Secession, Picasso metamorphosed his art style and career in a way that stayed refreshing and unique for decades.

A Cubist Commission in Brooklyn has found a very intriguing take on Picasso, a take which was sought after by many international museums this past year as they celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s death. The focus on a commission which started in one of the earliest stages of Picasso’s artistic career is a very alluring idea, especially seeing as it took place in New York City. The gloomy, reflective nature of the exhibit accurately portrays the era in which Picasso emerged in New York; monochrome and developing, suspended in between styles.

A Cubist Commission in Brooklyn has found a very intriguing take on Picasso, a take which was sought after by many international museums this past year as they celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s death.