From 250 Feet Up, Gregg Paravati Keeps Roosevelt Island Moving

For nearly five decades, Gregg Paravati has been New York City’s guardian, operating the Roosevelt Island Tram daily and watching the city change along the way. Now, he is the only remaining original tramway operator.

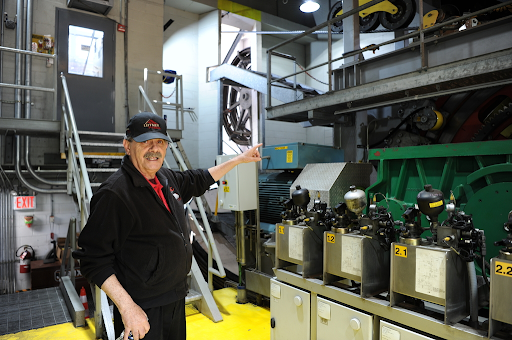

Gregg Paravati’s role in the tram cabin has changed over the years: whereas the original tram required more mechanical operation, today’s cabin is kept in motion by a computer system.

New Yorkers are best captured when they are in a constant sense of motion. As taxis dart between the intersections of downtown Manhattan and pedestrians weave through the sidewalks of Jackson Heights, New York City is propelled forward by a restless energy. Time accelerates and stops, ebbing and flowing within the urban rhythm.

Roosevelt Island sits in the heart of the city, an “improbably peaceful sliver of pseudo-suburbia.” As if in an act of defiance, time seems to take a gentler stride when it crosses the East River. Once housing only several hospitals and prisons in the 19th and 20th centuries, Roosevelt Island has now become an oasis in the middle of a relentless urban frenzy.

Roosevelt Islanders have a trifecta of transportation for getting on and off the island: the Roosevelt Island Bridge, the subway, and the tram — but the latter is arguably the most beloved. An intricate combination of cables and cabins, the Roosevelt Island Tramway is known as a lifeline to commuters, making a trip between the island and Manhattan possible within four and a half minutes.

With a steady hand and a keen eye, Gregg Paravati, 76, orchestrates the daily journeys of thousands. In a city known for its prominent underground transportation systems, the tram operator’s role may be lesser-known, but no less vital.

Mr. Paravati, a Bronx native, operates the tram five days a week, from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. As the tram doors close, he makes his usual announcement: “Good morning. If you’re standing, please hold onto a handrail or hand strap while the tram is in motion.”

Before he took on the role of the tram operator, Mr. Paravati worked as a filmmaker, freelancing and cutting television commercials. One February day in 1976, however, all it took was a spark of curiosity to begin what would become a lifelong career.

“I was living in Queens at the time, and when I was driving home on the 59th Street Bridge, I saw these new towers sticking up,” said Paravati. “I just got curious. I had never seen a tram before in my life.”

At the time, the Roosevelt Island Tram was still in construction. When the manager of the tramway approached Mr. Paravati in hopes of gathering a team of 30 tram operators, he accepted and was hired on the spot. The new group of ‘tram men’ soon began attending classes specifying what the tram was, how it worked, and how to operate it. Since the original tram had a Swiss design, Paravati and his colleagues often interacted with manufacturers from Switzerland. In May 1976, the Roosevelt Island Tram opened to the public.

The tram was initially a temporary fix to the lack of subway connection between Roosevelt Island and the rest of New York City. “They told us we were just going to have the job for around two years, and the tram was going to be demolished after the subway was built,” Paravati continued. “But two years turned into seventeen, and the subway still wasn’t finished. By that point, the tram became really popular, so it survived.”

Since then, Mr. Paravati has remained steadfast in his role, witnessing the evolving landscape of New York City unfold before his eyes. Roosevelt Island, for one, has changed drastically. Previously known as Blackwell’s Island and Welfare Island, it was once a quiet and somewhat isolated enclave, housing city facilities like a hospital, nursing residence, jail, and laboratories.

“The laundry facility was as big as a baseball field,” he laughed. “They would do all the hospital linens there.”

The Manhattan skyline, on the other hand, experienced transformations of its own. “Gradually, I watched the buildings grow taller and thinner,” Paravati remarked. Recommending a nighttime ride on the tram, he insists that when the skyline is lit up, the views from the tram are unparalleled. “I’d say the only comparable view is that of the Empire State Building, but that doesn’t move — we do.”

Whether it is the nostalgic rattle of the cabins or the friendly greetings among neighbors, the tram is more than just its functionality as a means of transportation. Aside from the tram’s panoramic view of New York City, Mr. Paravati refers to the experience itself as refreshing.

“I wake up every morning looking forward to that five-minute stretch of my commute, overlooking the East River,” said Tuilaepa Katoanga, a Roosevelt Island native. “Whereas the subway reminds me of how overwhelming everything above me feels, the tram serves as a reminder of how small everything is when you’re suspended hundreds of feet in the air.”

In every person is a sense of place, and Mr. Paravati’s story contains both the local and the universal. Despite spending most of his career up in the air, he remains grounded by the surrounding community: from Roosevelt Island residents to tourists from around the world, it is the people who have kept him at the tram.

“I love meeting new people and talking to them,” Paravati said. “I’ve met people from different countries all over Africa, Europe, island countries, you name them.”

In the 1980s, Mr. Paravati also forged an unlikely friendship with movie stars, such as Harrison Ford and Sylvester Stallone. As he operated the cabins while the celebrities filmed movies like Nighthawks on the tram, they often struck up casual conversation. Outside of filming, the Roosevelt Island Racquet Club drew lots of attention, where celebrities and political figures alike would relax over a game of tennis. “We would speak two, three times a week,” Paravati recalled. “It was pretty exciting.”

But when I asked him his favorite part of his job, he answered: “It’s the commuters, really.”

“We’re a family, we’re on a first-name basis, and we interact all the time,” he explained. “I watch the kids grow up, from their parents taking them to school to them commuting by themselves. Just the other day, I saw a group of students with their graduating caps and gowns. I’ve even been invited to some of their weddings.”

Bronx Science shares similar affections for the Roosevelt Island Tram. “Right after I arrived in the United States from Bangladesh, my dad took me to Roosevelt Island,” said Ayshi Sen ’24. “I remember asking him to take the tram back and forth multiple times, purely because it was fun and low-stakes — you didn’t really have to worry about what was happening, and it was affordable compared to other activities in New York City.”

Dasha Smirnova ’24, on the other hand, was initially skeptical about a ride on the tram. “I’m not a big fan of heights,” she commented. “But compared to the subway, the tram is surprisingly smooth and quiet. The first time I went, I didn’t even realize it had already brought us into the air.”

To many, Mr. Paravati’s presence is synonymous with reliability and comfort. Almost all subway or train commuters can empathize with the common frustration of missing the next train car by mere seconds, but riding the tram offers a more personal nature. “Some — actually most — mornings I’m running late, so I’ll get to the tram right before it’s about to leave. Without fail, every time, Gregg will wait for me before closing the doors,” added Katoanga.

Although the original group of ‘tram men’ from 1976 has disbanded, Paravati cherishes his current colleagues just the same. One woman who works with the payroll for the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation, or the RIOC, has been there since the first day as well, with others having worked 30 to 35 years. United in their dedication to keeping islanders moving, tram operators often attend parties and other local events around the island together.

Starting every morning at 6 a.m. and making a trip every seven and a half minutes, the tram operators are constantly going back and forth between the 60th Street station and Roosevelt Island. A microcosm of New York City’s hustle, the tram staff have developed their own culture. Outside of getting riders where they need to go, the operators have taken on another special role: setting up wedding proposals.

“Some people would rent the cabin and have their wedding ceremony right there,” reflected Paravati. “Other times, we staged proposals. When the guys wanted to get engaged on the tram, we would pretend we knew nothing about it and act as if the tram got stuck over the East River. Then boom! He dropped down on one knee. Once we got to 60th Street, the couple’s friends would be waiting with video cameras.”

Almost in a wit of irony, the Roosevelt Island Tram stopped in midair for nearly twelve hours in 2006.

Mr. Paravati was not on the suspended tram — his workday ends at around 2 p.m., while the incident occurred at around 5 p.m. This occurrence, among other reasons, led to the RIOC’s decision to shut down the tramway and refurbish its internal systems in 2010.

“We were out of work for around nine months, on unemployment and waiting to get back,” he remembered. For Roosevelt Island residents, life without a tram seemed foreign. The cherry-red sky trolley was essential to the island’s culture, signifying accessibility to the elderly and disabled residents, as well as the necessity of urban exchange. Without it, residents got a taste of a past lifestyle, one that Paravati understood firsthand. Micah Kellner, a former state representative for the district, remarked that the tram was no longer a luxury, and the still-limited options mean residents live in fear of losing all three modes of transportation at the same time.

In November 2010, the RIOC reopened the tram: this time with fresh paint, stronger cables, and a new French design. Instead of being attached to each other, the cabins could now move independently in either direction. The corporation also added more backup systems and emergency kits — blankets, water, food, and a toilet with a privacy curtain — to each cabin, hoping to ensure an emergency like the 2006 incident would never repeat itself.

Modernization and improved systems mean that many of the tram operator’s responsibilities in the cabin have transferred to computers. “We start it, we can slow it down, we can stop it if needed,” Paravati detailed. “We can’t bypass the system from the cabin, though. If anything happens, I would call a supervisor in the control room on a radio. And if for whatever reason we need to shut the cabin down, we’ll just move over to the other cabin. But that doesn’t normally happen, because usually the control staff will bypass the minor issues and the system resets itself.”

To Mr. Paravati, building Roosevelt Island’s transportation system up from scratch was a feat on its own. Before the Roosevelt Island Bridge, the subway, and the tram were built, life on the island was trademarked to seclusion. He recalls taking a trolley from Manhattan onto the middle of the 59th Street Bridge, where elevators would then take visitors down to the island. “For the most part, people would visit their families in the hospitals. Those things could carry trucks and cars too, for delivery and pickup,” he said.

Paravati noted that now, despite transportation being more convenient, it loses some of the original sense of sentimentality. In 2004, the RIOC replaced the traditional tokens with the MetroCard in an effort to more fully integrate the tram into New York City’s public transportation systems. While most commuters found this shift convenient, other residents, young and old, preferred the old-school feel and associated the tokens with fond memories from their youth.

Another change may be edging closer: replacing MetroCards with the OMNY system. Already taking the rest of New York City by storm, OMNY, or One Metro New York, seeks to expedite the fare process through phone taps and contactless payment. For the most part, Roosevelt Islanders have held off on strong opinions, opting to remain neutral as long as the MetroCard is still an option.

Currently, there is no publicly available timeline for the implementation of OMNY; in fact, because the tram is under the jurisdiction of the RIOC and not the MTA, the two corporations still need to negotiate a balance of power and bridge the fare disparity. With controversy surrounding the MTA raking in millions of unearned dollars and the RIOC’s seeming “cowardice,” local journalists argue that it is ultimately the island residents who bear the brunt of corruption.

From Mr. Paravati’s point of view, even though transportation is becoming much more convenient, the influx of visitors to Roosevelt Island can make it difficult for commuters to get onto the tram, especially on weekends. Getting to know so many residents on a personal level means he approaches this issue from a place of care, empathizing with the local community first.

Outside the tram cabin, Mr. Paravati leads a simple life. He has his own commute to the tram station every day, driving twelve miles from his home in New Jersey. Lamenting that afternoon traffic turns the 25-minute drive into an hour and a half, he strives to begin and end his workdays early.

When he was younger, Mr. Paravati was part of an acapella group that would meet and sing together on the weekends. Now, he spends his weekends traveling with his family, often paying visits to upstate New York or down to the Jersey Shore. During the summers, he takes Saturdays off.

Life beyond the tram is enjoyable, but in a way unimaginable, too. In 2016, Mr. Paravati had planned to retire, admitting that the thought crossed his mind more than once.

Then, a medical procedure took him out of work for around four months. “When I was recovering, I thought to myself, ‘Jesus, it’s only been four months and I’m bored to death.’ So I went back to work, and that changed my mind,” he explained. “I’ve stayed ever since.”

Gregg Paravati is a constant in a city full of variables. In the midst of a changing New York, Paravati anchors the smaller Roosevelt Island community: a familiar face and an emblem of continuity, he reminds residents of the spirit that makes their island home. Just as his unwavering lifelong career has impacted the community at large, the reciprocal nature of his job has left an indelible mark on him as well.

“It keeps me alive,” he chuckled.

“We’re a family, we’re on a first-name basis, and we interact all the time,” Paravati explained. “I watch the kids grow up, from their parents taking them to school to them commuting by themselves. Just the other day, I saw a group of students with their graduating caps and gowns. I’ve even been invited to some of their weddings.”

Charlotte Zhou is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ In addition to writing and editing articles, she constructs the online crossword and...