Vivian Maier: The Mary Poppins of Street Photography

The mysterious photographer who left behind so much, yet so little.

Here is an exhibition of Maier’s photographs at Dunkers Kulturhus in Helsingborg, Sweden in 2016.

Highland Park, Illinois, 1950s.

A tall, serious-looking woman walked down the street with three boys. She appeared to be just another typical middle-class neighborhood nanny. Her pixie-like haircut, and her collared blouse tucked tightly into her calf-length skirt, all covered up in an oversized men’s coat; nothing special about the woman would have caught your attention – except for the Rolleiflex camera slung around her neck. While keeping the children in check, the nanny observed her surroundings and seemed to be taking photos. When she returned home, she cautiously locked the door of her attic bedroom behind her, took out the film from her camera, and placed it in a box alongside shoulder-high stacks of hoarded newspapers, mail, and receipts.

Chicago, Illinois, 2007.

A real estate agent named John Maloof bought a box of photo negatives at an auction house for $380. As he scanned the negatives, he was astounded by what he found: thousands of captivating and skillfully composed images documenting the lives of people in the cities in the 1950s and 1960s, comparable to those of the best photographers of the era. Over the course of a year, he managed to collect 150,000 negatives from others at the auction. Maloof knew that what he discovered was a true photographic treasure.

Vivian Maier, Maloof learned, was the owner of the box. Who was she? Why couldn’t he find any of her information on the internet? If she were a photographer, why did all her negatives remain undeveloped? It was only until 2009 when Maloof saw a brief obituary that Maier passed away recently he realized that she had been a nanny. But Maloof’s question remained unanswered. From there, he embarked on a journey to find Vivian Maier.

Vivian Dorothy Maier, Maloof learned, was born in New York City in 1926 to a French family. She spent her childhood moving between France and the United States, which would explain her French accent. In 1956, Maier relocated to Chicago’s North Shore, where she worked as a nanny for the next 40 years.

In the documentary “Finding Vivian Maier,” Maloof conducted interviews with Maier’s former employers in hopes of learning more about her. Most of them would agree that she lacked interpersonal skills and was extremely private, which prevented her from maintaining relationships with others. She would demand additional locks for her room. She disliked physical contact and attention. She refused to give out her real name. When asked what she did for a living, an acquaintance recalled Maier replying, “I’m sort of a spy.” In fact, most of the people Maier knew did not know she was an artist; most simply knew that she took photographs.

However, Maier’s personality proved to be advantageous as she was able to successfully diminish her presence in the course of seeking authentic and unaffected photos of her subjects. Who could have ever imagined that a person who had so much difficulty expressing herself could capture such openness, depth, and life through her photos?

Maier’s journalistic instinct allowed her to capture the ordinary in an extraordinary way, the fleeting moments before they were gone. She shot in light and shadow, from above and below, and her subjects ranged from the rich to the poor, the young to the old, the fashionable to the antique. Among the genres she explored were architecture, cityscape, portrait, self-portrait, and street. She was an artist experimenting tirelessly with various mediums, cameras, films, and cropping formats.

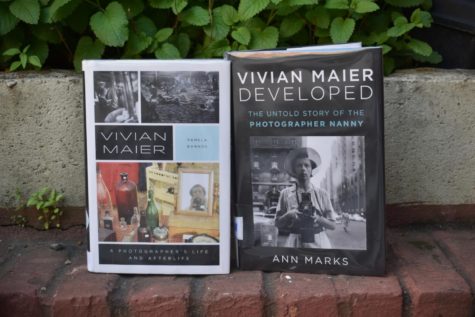

It was in 2009 when Maloof decided to share Maier’s pictures with a wider audience. He started a blog showcasing a portion of her photographs and shared it with the Hardcore Street Photography group on Flickr, which soon went viral. Maloof then partnered with the Chicago Cultural Center for a January 2011 exhibition, igniting a frenzy over a mysterious nanny who was also a world-class photographer. Vivian Maier’s story is turned into books and award-winning documentaries. Her prints are exhibited at museums around the world.

It is estimated that Maier took more than 200,000 photographs during her lifetime. Many have wondered why her negatives remained undeveloped and her photographs unpublished. We will never know the answer to this question. But in a rare audio recording of her, Maier revealed her outlook on life: “We have to make room for other people. It’s a wheel – you get on, you go to the end, and someone else has the same opportunity to go to the end, and so on, and somebody else takes their place. There’s nothing new under the sun.”

Maier might not have regarded her work as particularly noteworthy. She was merely observing the fast-paced world because to Maier, photography was not only an instrument for self-expression but also a conduit between her and the thousands of diverse and interesting people she had encountered. In that sense, she was happy to remain on the outside looking in.

When asked what she did for a living, an acquaintance recalled Maier replying, “I’m sort of a spy.”

Wendy Lin is an Academics Section Editor for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook. She fell in love with photography in sixth grade after taking her very first...