When I swim, a multitude of emotions rush through my head. Sometimes I plan or stress; other times, I simply ponder. Humans seem so insignificant, and I feel the same about myself. I wonder about the impact of my actions on the world. Does what I do matter? Perhaps I can lead a happy life being average? Maybe not.

When I’m in the water, I sing to myself. Random songs plaguing my memory fill my mind while I swim. Sometimes my mind will play that Disney song I listened to with my sister four months ago or my uncle’s musical creation. However, on rare occasions, I don’t think at all. My mind isn’t empty; it flows.

Experienced athletes often enter this state of flow, often referred to as “the zone,” the epitome of athletic performance. Flow has little to do with physical well-being but rather one’s state of mind. According to Hungarian sports psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, being in the zone means being fully immersed in a singular task. Csikszentmihalyi attributes the flow state to the genuine joy of completing the task, separating it from materialistic, social, or monetary rewards. The pride and satisfaction in doing is what allows for the epitome of mental focus that defines the zone.

The zone is most commonly associated with athletics, but it is a level of immersion achievable in almost any task. The zone is the mental state in which the task at hand dwarfs all else, temporarily erasing every other goal, worry, and thought. The task, however, doesn’t have to be physical. Writing a novel, cooking a meal, or even verbal debate can bring people to their zone. However, finding the zone is easier in more physical tasks due to the higher focus they warrant. Swimming is the perfect catalyst for entering the zone. With no visual distractions and a relatively simple physical pattern, the only challenge left to overcome is mental control.

It’s impossible.

To try to enter the zone is impossible. I’ve tried. Attempting to enter the zone and diverting your focus to something outside of the task leaves you even further from peak productivity. That’s why when I’m swimming, I never let myself try to enter a state of flow. Trying with a goal of nothingness is futile, and I prefer not to anger myself when I swim. Instead, I let my mind wander. Physical activities like swimming have a meditative quality, allowing reflection. I often find that the rhythmic motion and sensory experience of swimming create a conducive environment for contemplation. I question myself and often formulate my own opinions on news, people, and even myself.

It’s when I swim that I create my self-image. Unlike many other competitive swimmers who think about food or geography – like Zachery Fan – I formulate my perception of myself. I don’t linger on what others think of me, whether the girl in my math class believes I’m incompetent for asking for a pencil or if my mom wants me to soak my plate after eating. Instead, I think about how I view myself and whether I am doing enough to improve myself physically and mentally.

When I am looking inward, I usually find a deep focus that helps me stay out of my own way, and I enter a deep meditative state where I find peace in my actions.

Once I have reflected on myself and don’t focus on what’s at stake, I smile, knowing that I am inadvertently performing at my best.

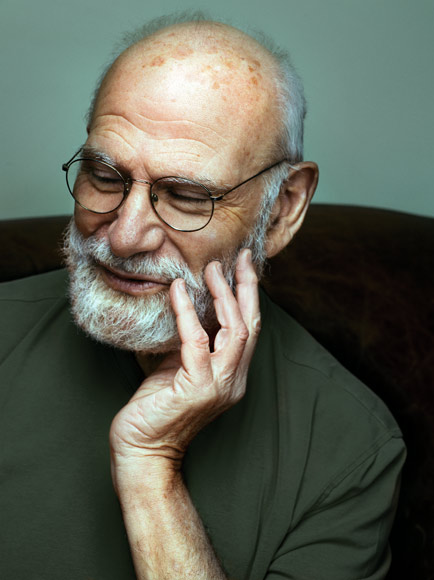

While my thoughts drift from random to strategic, even fully disappearing at times, others have different experiences swimming. Oliver Sacks drafted an entire article while doing the backstroke, only swimming to the water’s edge to write his ideas on paper. He even sent his article to The New York Times while still wet from the lake. Sacks (1933-2015) was an acclaimed British neurologist, naturalist, historian of science, and writer who greatly benefitted from his time in swimming.

Samuel Sacks, a Jewish WWII survivor and physician, would swim every day until the age of 83. His physical condition did not hinder his swimming and, as a result, kept him in an able physical condition. Both Oliver and Samuel Sacks greatly benefited both physically and mentally from swimming.

Swimming forces thinking, which prevents depression and other mental ailments. Additionally, swimming reduces the risk of dementia, a terrifying disease that often plagues people as they get older. Swimming causes recreational hypothermia in which “cold shock” neuro-protecting proteins are produced and released. Along with the countless benefits swimming has on mental health, there are excellent physical conveniences as well. Swimming is a great opportunity for low-risk exercise and even prevents certain physical diseases like osteoporosis, as the work done against water increases bone density.

Swimming is relatively light on your joints when compared to almost every other common exercise – such as football or running – but it still provides muscle strength and cardiovascular endurance training. Overall, physical activity improves cardiovascular and muscular endurance and can greatly benefit one’s mental health.

While the reflection caused by swimming is incredibly beneficial, the brain benefits even further from the exercise itself. The brain is an organ that, just like any other, receives nutrients and oxygen from the blood. Exercising helps the brain develop and get its nutrients and oxygen at a healthier rate, often making a person feel rejuvenated. Furthermore, exercise supports nerve cell growth in the hippocampus, a complex part of the brain, which helps strengthen nerve cell connections and further lowers the risk of depression and other mental health issues.

Exercise manages stress by providing clear goals that help distract from paranoia, anxiety, and depression. With the added benefit of being one with nature, the brain is given time to rest, relax, and rejuvenate. Exercises that stimulate the mind relieve stress and improve memory, attention, concentration, and impulse control.

Overall, swimming is a great way to find oneself through physical exertion. It gives time for analysis, contemplation, and, if fortunate, the ability to focus on nothing despite everything, allowing entry into the zone.

While many flourish in a multitude of ways while swimming, others experience stress from swimming and prefer other forms of exercise. Skyler Lu, former D1 Princeton swimmer, thought mainly about perfecting her stroke while swimming, looking to tackle any weakness and overcome any obstacles. However, now that she has ended her swimming career, she runs and can focus on nothing. According to Skyler, she “zones out,” but in reality, she may be zoned in, focused on such a simple task that it seems she’s focused on nothing.

Sasha, the younger sister and a former D1 swimmer for Brown reflected on the physical and mental effects of swimming. When discussing the impact on her mental well-being, she stated, “It helped me build a sense of mental toughness and discipline.” Sasha added that swimming “definitely challenged my mentality in many ways, but I was able to grow.” This highlights how swimming helped foster a robust mental fortitude that she continues to draw upon today.

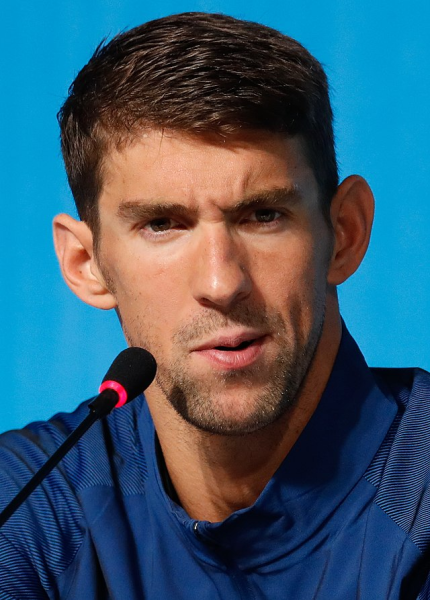

However, despite the multitude of benefits associated with swimming that range from physical to psychological, the negatives cannot be ignored. Micheal Phelps suffered from depression, Hector Pardoe suffered from a career-ending eye injury, and almost every swimmer I know suffers the mentally draining side effects of swimming. Even my little sister – a passionate swimmer – will complain about the wrinkles on her hand or having to dry her hair.

It’s easy to complain and find negatives, but everything has downsides. While it’s important to recognize these possible faults, we must grasp the benefits and incorporate exercise as a time to reflect on one’s thoughts.

Overall, I have found swimming to be a positive experience for myself, many of my teammates, and the college swimmers I’ve spoken to. The physical and mental benefits outweigh the drawbacks, and while the commitment has been tiresome, being aware of my dedication makes me temporarily happy and permanently fulfilled.

Overall, I have found swimming to be a positive experience for myself, many of my teammates, and the college swimmers I’ve spoken to. The physical and mental benefits outweigh the drawbacks, and while the commitment has been tiresome, being aware of my dedication makes me temporarily happy and permanently fulfilled.