Graffiti as Art

Some see it as an ugly blemish. Others view it as a costly act of vandalism. And to a burgeoning minority, graffiti has become a medium of art for appreciation and for self-expression. Graffiti has been around since antiquity, and it has always been ubiquitous in urban areas. The very word comes from the Italian graffito, to scratch, which itself is descended from the Greek graphein, to write. However, today’s elaborate aerosol spray murals or simple scrawls differ greatly from the scratched poems and proclamations of the Ancient Romans. In both cases, graffiti is an under-appreciated insight into the contemporary culture of its creator, be he from Pompeii or Rio de Janeiro, rather than an act of criminal vandalism.

The simple, monochrome scribbles of graffiti writers’ pseudonyms (called tags) are all too common in New York City. They are the most characteristic feature of graffiti, and their prevalence in New York City serves as a reminder that it is the birthplace of modern graffiti. During the 1970s, graffiti writers began to excessively tag subway cars. As the trains made their journeys around the city, their writer’s works gained exposure and helped to bring them recognition.

The bombing (prolific writing and covering of an area with tags or pieces) of trains continued well into the 1980s. In 1983, much to the joy of graffiti writers, white subway trains debuted on the Number 6 line. These trains were blank canvases in the eyes of graffiti artists, and whole car pieces began to flourish (whole car pieces are now most commonly used by companies as advertisements, most notably on the 42nd Street shuttle). Visitors to the city absorbed the new medium and carried it back with them to France, Great Britain, and Brazil, among other countries, where it began to evolve independently of the New York scene and produced the likes of Blek le Rat, who is considered to be the father of stencil graffiti.

This early golden period of graffiti was somewhat ephemeral. Spurred on by complaints, the city’s government worked with the transit authorities and the MTA to buff out (remove graffiti pieces through any means) pieces on trains and to prevent future cases. As a result, graffiti burst out into the streets of the city and spread out from New York to previously undisturbed urban areas. Rooftops and billboards became the successors of whole car pieces as choice canvases, but large, extravagant pieces became increasingly fewer in number. When coupled with the heightened negative social stigma around the act, it seems that the ‘War on Graffiti’ was won by the mid 1990s.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme. The efforts of city governments and transit authorities to eradicate graffiti zeroed in on cleaning the streets and reducing crime, completely ignoring its social and artistic aspects. Ancient Romans “threw up” caricatures of their politicians, the Crusaders tagged churches and mosques in Jerusalem, and Michelangelo carved his name in Nero’s Domus Arena, as did Lord Byron in the Temple of Poseidon in Greece. What was the driving force behind their actions?

Throughout the course of history, cities and other urban centers have always been places of colossal human conglomerations. The individual has a history of being shouted out by the masses, losing his idiosyncrasies and persona to become another speck in the crowd. It is within human nature, however, to express oneself and to stand out from the rank and file. The despondent economic situation in one of the largest cities in the world and the loss of voice is what most likely led to the creation of modern graffiti in the 1970s. Graffiti, like paintings, is more than a drawing. It is a medium for self-expression and communication, though not recognized as such.

Forced from the trains and onto the streets, graffiti artists now had to work much more delicately than before. They began to pick locations that were hard to reach, where they couldn’t be found, and took the surrounding environment more into consideration when creating their pieces. An abandoned train tunnel running along the Hudson River became a choice spot for those in the city. There, the most artistic pieces are found illuminated below brief grating breaks in the long, dark stretches of the tunnel. It became one of several havens for graffiti artists, populated most frequently by the tagger known as Freedom, from which it derives its name.

One of the most well known writers of contemporary times, Banksy, is incredibly popular even amongst the public for using space to create poignant, witty political jabs or remarks about society at large. His works include a response to the burgeoning use of closed circuit cameras in London and the UK, a massive, yet simple piece – “ONE NATION UNDER CCTV”, a simple quote on a London wall – “If graffiti could change anything, it would be illegal,” the image of Death on the bank of the Thames as a symbol of its dilapidated and polluted state, and a piece of a pole vaulter jumping over a fence, landing on an abandoned mattress, created in time for the London Olympics.

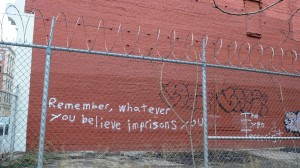

In New York, bright, gaudy wheatpaste stickers pepper lampposts and walls, especially in SoHo and Lower Manhattan. SoHo itself is one of the few several places where a plenitude of various graffiti pieces and styles can be found, including yarnbombing (pieces created with yarn, usually wound around fences). The Typo Terrorist created a rather straightforward piece reminiscent of Banksy, which simply says, “Remember, what you believe imprisons you,” yet it is its position behind a barbed wire fence is what lends it great profundity and exemplifies the writer’s use of space, as well as his ability to deliver a poignant, thought-provoking message through graffiti.

Chinatown and the Lower East Side are likewise populated by extravagant graffiti. The largest haven for graffiti writers in New York is 5Pointz (Chase Guttman’s article further explores this location: ), a hulking warehouse covered in sanctioned graffiti. It has been occasionally described as a live graffiti museum, where a lucky visitor may even have the rare fortune to witness a piece being created.

5Pointz and Freedom Tunnel are not the only graffiti ‘museums’ in New York City. In the past decade, prolific and preeminent writers (such as Banksy) have donated their works to the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Brooklyn Museum. This, however, has evoked a bitter response from other writers. They are against such gentrification of graffiti on the grounds that graffiti exhibitions take from the core essence, value, and worth of graffiti pieces by removing them from them natural element in the streets and transplanting them into unnatural environments.

Our opinion of everything that we observe is dependent on our perspective. Perceiving graffiti as mere vandalism and not as a work of artistic expression causes us to see it as just that, and we lose the ability to discern the writer’s message, meaning, or purpose. Graffiti is a uniquely urban phenomenon. It would an absolute travesty to lose such a novel, unparalleled art form due to the close-mindedness of society at large.