With 8.4 million people packed into 309 square miles, New York City is one of the most urbanized areas in the world. Each day, residents travel from block to block and borough to borough. The city facilitates these commutes through its developed sidewalks, large bike lanes, and extensive bus and subway system.

Despite the variety of transportation options, cars are still commonly used. Yellow taxis are practically a staple of New York City and other car services like Uber and Lyft continue to grow in popularity each year–as of 2023, Uber had 150 million active users and Lyft had 21.4 million active users. In boroughs like Queens or the Bronx, where the MTA’s (The Metropolitan Transportation Authority) web is not as widespread, cars are a necessity.

Mia Jansson ’25, a Whitestone resident, said “cars are pretty essential if you don’t want to spend a lot of money.”

She deals with the same commuting conundrum that many other Queens residents face. “There are a lot of buses in my area of Queens but the express buses are seven dollars, and it’s more time-consuming than the subway, of course. If I don’t want to take the express to the city, it’s a 30-minute bus ride, and then the seven [train] from Main, and that also adds up if you’re doing it a lot,” Jansson explains.

The widespread usage of cars is harmful to the environment and residents of New York City. Emissions from motor vehicles (cars, buses, motorcycles, trucks) contribute to 11% of the city’s fine particulate matter (PM2.5). PM2.5 exposure results in heart diseases, lung diseases, and even death.

To solve this issue, a $15 congestion charge for driving below 60th Street in Manhattan is planned to be implemented later this year. The goal of this fare is to promote the use of public transportation, thus decreasing congestion in New York City.

However, New York City’s recent push to decrease car emissions is negated by the constantly increasing public transportation prices. On August 20th, 2023, MTA fares were increased from $2.75 to $2.90, in line with their plan that was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

An alternate form of transportation that many city-dwellers tend to overlook is bikes.

“It’s good for the environment, it’s fun, it’s good exercise, it’s really pretty, and it’s really scenic,” said Liza Greenberg ’25, a Citi Bike user for three years.

When it comes to combating climate change, Citi Bike reduces carbon emissions by 1,800,000 pounds each month. Considering that in 2021 New York produced 156 million tons of carbon emissions, it amounts to a significant dent.

The benefits of Citi Bike are amplified by its implementation of electric bikes (Ebikes).

Manual bikes require pedaling, which is significantly harder in a city like New York where you are either flying down or trudging up a hill. Ebikes alleviate this problem by allowing its riders to go faster at the expense of less energy.

Also, simply learning how to ride a bike in a city is difficult – there are not a lot of empty parking lots or streets to practice on. So, Ebikes act as a first step towards riding manual bikes.

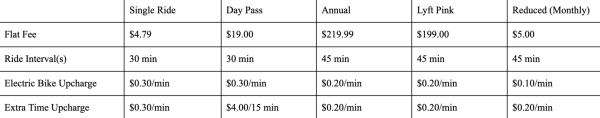

Citi Bike offers multiple payment options to accommodate everyone in New York City. Tourists may utilize the single or day passes while residents can opt for annual plans.

“I calculated it, and if I can bike somewhere in under 20 minutes, then it’s cheaper for me to use a Citi Bike than take the subway,” said Maya Hafeez, a college student at Barnard, and a Citi Bike user for four years.

To aid low-income residents with affording Citi Bike, there is a reduced payment plan available. It is applicable to those who live at NYCHA, JCHA, and HHA along with SNAP recipients.

But affordability alone will not incentivize these residents to start using Citi Bike.

New York City is known for its notoriously delayed subway system and slow buses. So, people need a convenient mode of transportation.

Since bike traffic barely exists in the city and the time a bike leaves the dock is fully reliant on one person, the rider, the issue of timing is bypassed. “Citi Bike is always dependable,” said Greenberg.

Still, the most vocal complaint in The Science Survey’s last article on Citi Bikes was the program’s lack of accessibility.

Citi Bike was first implemented in May 2013 with 6,000 bikes in Manhattan and Brooklyn. The lack of boroughs mentioned may allude to the problem – all of Citi Bike’s great aspects can be negated by the inability to find a bike.

Now, due to a partnership with Lyft, Citi Bike has grown to host almost 40,000 bikes spread across Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Lyft’s $100 million investment into Citi Bike came in exchange for another bike share system to add to their ever-growing roster.

The City’s contract with Lyft has two notable stipulations to promote accessibility – 90% of the fleet being available to the public at all times and not having stations completely empty or full for over two hours during non-peak time and one hour during peak time.

When the plan was announced in 2019, Mayor de Blasio stated that “this expansion will help us build a more fair and equitable city for all New Yorkers. Even more communities will have access to this low-cost, sustainable mode of transportation. With double the territory and triple the number of bikes over the next few years, Citi Bike will become an even better option for travel around New York City.”

Lyft’s expansion plan ended in 2023. So, have Citi Bike users noticed a difference?

“For me, I would say it is pretty easy to find places or stations near my neighborhood to drop bikes off and pick them up. I live on the Upper West Side, and there are a lot of Citi Bike stations,” said Greenberg.

The sentiment is shared by Hafeez who said, “The station outside my apartment on 116th and Broadway used to only have three or four bikes, but now there are at least 15 every day, which is nice.”

Unfortunately, this availability does not seem to stay constant throughout the city. “The further uptown you go, the fewer bikes there are to use. Especially the electric ones, which is frustrating, because uptown is the most hilly area where you need the electric ones the most,” said Hafeez.

New York City has acknowledged the disproportionate bike distribution, especially within areas that are mainly low-income or people of color.

The rapid growth in docks and bikes is causing relocation programs like Bike Angels – a system that rewards riders who move bikes from a full docking station to an empty docking station with points that can be used towards Citi Bike amenities – to be rendered ineffective. Simply put, the number of bikes are outnumbering the number of Bike Angels. Furthermore, Lyft is unable to keep up with the maintenance needed for such a large fleet of bikes.

The proposed solution is to have the city play a bigger role in relocating bikes, primarily by enforcing fines on Lyft for not adhering to the previously mentioned standards in their agreement.

Despite the clear progress that is still needed, Citi Bike is now significantly more influential than when The Science Survey last looked at the issue in 2021 thanks to the Lyft expansion — there is no ignoring the overall upturn in Citi Bike users.

Thus, more and more people are realizing the environmental, financial, and convenient benefits of biking.

“It really makes me feel like a part of the city in a weird way,” said Hafeez.

“It’s good for the environment, it’s fun, it’s good exercise, it’s really pretty, and it’s really scenic,” said Liza Greenberg ’25.