Tell Me What Consistency Looks Like: How Defined is One’s Personality?

I can’t figure out my personality. Can you?

Kathryn Le ’22 said, “There’s no perfect word that can describe me. It’s not a question that we all think about every day. What are words that describe myself? What are words that describe my personality? I say ‘I guess’ because it’s kind of weird just praising myself, so I wasn’t really sure. Maybe it’s something I see in myself, but it’s not how I actually come off to others.” (This graphic was developed on Canva.)

My greatest fear is for someone to come up to me and tell me: “You’re an INFP.” If this someone knew me for a day or two, I would maybe forgive them. If we knew each other for more than a month, I would turn a little tense but nothing too extreme. And if this should ever occur a few years into our relationship, well then, that person better apologize to me.

Yes, for those who are now hesitant to ask, I will admit that I have taken the Myers-Brigg Type Indicator (MBTI) Test three times, and my results have been INFP-T (Introvert, Intuitive, Feeling, Prospecting, and Turbulent), the Mediator, every time. My Enneagram type is four, the Individualist, with a five wing, the Bohemian. My Dungeons and Dragons alignment is chaotic evil. My Big Five personality scores are 79 for openness to experience, 38 for agreeableness, 54 for conscientiousness, 96 for negative emotionality, and 33 for extraversion.

It is hard to believe that — according to the mother-daughter duo, Katherine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myer, of the ever mainstream MBTI Test — the nearing 8,000,000,000 members of Earth could be categorized in 16 personalities.

Zawad Munshi ’21 told me he was also an INFP but was on the edge between introverted and extroverted. On that scale, I lean more towards introverted.

I responded with a shaking index finger pointing upward and a smile, “That’s crazy because I’m also an INFP.”

“Amazing. We’re literally the same person.”

I once read a poem by Wendy Cope called “Does She Like Word Games?” This sent me into a state of surprise. I do not take any issue with the contents. I actually enjoyed it — it worked against evaluations and revealed the innate, harmless hypocrisies of human nature.

And yet, the title still bothered me. It reminded me that people have the ability to evaluate me, and they will do it if they feel even the slightest compulsion to do so. I imagine two people sitting in a booth. One of them thinks they know me well when, in fact, they know me only scarcely. This person, who I picture as an old friend of mine, is telling the other all about me. The other leans in and whispers conspiratorially, “But can she even hold a job?”

This image, I realize now, is very much colored by scenes in films in which two middle-aged women gossip about everything and everyone. I wish that I could run into that frame and furiously scream, “Can everyone please just stop analyzing me?” Much like everyone else, I am not a character in a book or a TV show or a Canadian goose at the pond (though I like to think they do not enjoy the judgment very much either).

It appears that most psychologists define personality as the characteristics of an individual based on consistent behaviors, thoughts, and feelings, rendering the phrase “inconsistent personality” oxymoronic. This definition greatly disturbed me.

Consistency is not a quality I claim. I cannot help but feel envious of the people who know they are creative, know they are mean, know they are smart, or know they are odd. I cannot even figure out if I am ever-changing.

I settled to talk to some Bronx Science students about their experiences with coming to terms with their personalities.

The first person I talked to was Selina Li ’22. I have known her since the beginning of our first year at Bronx Science and have spent a decent amount of hours after school together.

I asked the question, “How would you describe your personality?”

As if the air molecules in her living room threatened to close off, she responded within a second, “I think my personality is eccentric. I don’t know a nicer way to say it.”

Now that we are sitting down to talk in a setting that does not involve work, I have learned that she does, in fact, have much more to say. She always finds ways to fill the silence. She aired her fear of not getting married, questioned whether her self-proclaimed “savior complex” over “some people who are worth being judged on Instagram” is justified (of which, she concluded a concrete yes), proposed her theory that a college student is smarter than Albert Einstein, delineates how her course load would be better if she did not have that certain teacher in ninth grade, and — I’ll stop here for now.

She was even up for a demonstration of her dog barking skills, which was inspired by a passing TikTok video. Throughout the forty minutes we spoke, she never failed to constantly smile and laugh. She spoke to me how I think to myself while walking circles around my kitchen or in front of my bathroom mirror at 4 a.m. It’s a nice thought exercise to imagine what goes on in her mind. I don’t know what’s going on exactly, but I know this is how she acts in the other environments I’ve been around her, and I know she’s consistent.

When I cut myself off seeing that she was eager to continue her spiel on I don’t know what, she interrupted, “No, no, no, you can go. I have nothing to say. I was just ad-libbing.”

Distributed three separate times throughout the conversation, I asked, “Do you have any hesitancies with calling yourself ‘eccentric’?” She immediately answered no, brought up her unideal relationship with social cues, and laughed off how her talkative and digressive nature “make[s] other people uncomfortable.”

Selina recommended that I interview Tobias Alam ’22 next because he “makes you wonder whether you can just pick apart his head.” He joined me on the Zoom call just as Selina was leaving. I sat next to him for some months in math class last year and saw him here and there. Other than that, my connection with him, at the time, was sparse.

When asked the question, he answered without hesitation, a seamless flow of words suggesting he came prepared though he did not know why he was here at all to begin with, “Here’s the thing: I can always say the generic ‘I’m introverted. I’m interested in this and that hobby.’ But I think personality is something that’s always changing, constantly in flux depending on what kind of conditions you’re surrounded by. It’s really hard to actually pinpoint what’s your personality. At the end of the day, it boils down to ‘what do I like doing now and what do I dislike?’”

He continued, “Personality is a false category. People synthetically create categories to make analyzing stuff easier, like analyzing characters in a book, analyzing other people — useful for sociologists and psychologists. Because it’s a synthetic thing, it has its limitations inherently.”

In response to the very concept of “personality,” he said, “I don’t think personality exists at all to be honest. It implies some kind of permanence, at least a temporary permanence. I don’t think you can boil down personality to a single word.” This is a temporary permanence, if temporary, in this case, means two days, I would like that.

After he bemoaned distilling personality into one word, I, of course, had to ask, “If you had to describe your personality in one word, what would you say?”

“I’ll describe it with this kind of analogy: if you give some people some kind of stimulus, they will jump at it completely. I hesitate before jumping into anything.”

“Kind of like, you think before you act?”

“I definitely do not.”

“Interesting.”

“It’s not even thinking. I hesitate before jumping.”

“So, hesitant?”

“Yeah, probably.”

“Do you have any hesitations with what you just said?”

“Yeah, a lot.”

Categorization simplifies. In that simplification, complications arise. I tell you Selina is eccentric. I tell you Tobias is hesitant. But how can I be so sure? How should I explain Selina’s story in which someone tells her she is “the most average person I’ve ever met”? How should I explain Tobias’s tone of finality and certainty with which he speaks? How should anyone explain any of this? Why should anyone attempt to explain any of this?

There’s a hollowness in my heart that arises out of simplification as if what I just experienced was capable of reduction and wasn’t as beautiful or as special as I once believed. Specific anecdotes littered with contradictions also happen to be much more interesting.

Inspired by the stark juxtaposition between the two, allow me to propose the Selina-Tobias Spectrum. On the Selina end, personality is evident in every story told, word said, sound made, and breath released. This is known and this is consistent. On the Tobias end, one is hesitant to say they are hesitant. This is an idea to be hesitant about.

Then, I went to Jillian Chong ’22, a good friend of mine since second grade. When I asked her the question, she paused for eight seconds, a silence usually met with close-lipped smiles teetering on the edge of laughter. It should be an easy question. After all, one expresses themself every day in the act of living. It’s a surprising thing that life should prove otherwise.

“Like in one word?”

I viewed her question in response to mine as a product of a time-sensitive society bewitched with the brevity of summaries: key takeaways, advertisements, elevator pitches, not to mention actual summaries. I recall how Tobias said, “I don’t think you can boil down personality to a single word,” though I had never asked him to do so and encouraged him to say as much as he wanted. This is an assumption being made without much doubt. It’s not that I fear summaries, but what’s stopping me — or I should ask this of everyone — from giving ourselves more time?

Jillian believed herself to be an introvert. She explained, “I feel like that defines a lot of what I do. I don’t choose not to make a lot of friends: it just comes naturally to me. In social interaction, it’s a lot harder for me to think about what I’m going to say compared to other people who are better at public speaking. Something about being introverted is that I form closer friendships, so that the relationships I form are actually meaningful and they last, which is nice.” She added on her tendency to overthink a lot, which she believed leads to slow decision-making and less trust in others.

“Do you feel secure in yourself?”

“I thought about this a lot. I think I do. I wouldn’t really change my personality because it’s a lot of work. But also I really do like that I’m introverted.”

“I’ll ask you again: how do you define your personality?”

“Um, again?”

“Yeah.”

“I really should have saved being an over-thinker for this question.”

“I know you’re more than an over-thinker. I know you’re more than an introvert. What’s your personality?”

“Uncaring,” she said with a laugh. “I can’t think of anything. Okay, I can just expand on my introverted thing. I do really think I’m an introvert.”

I asked again, “Do you agree that you’re introverted?”

“Yes, I do. One hundred percent.”

“Okay—”

“Do you want me to expand on that?” she said with a snicker. “Are you conducting the interview or am I?”

Oliver Hendrych ’22 landed around the middle of the Selina-Tobias Spectrum.

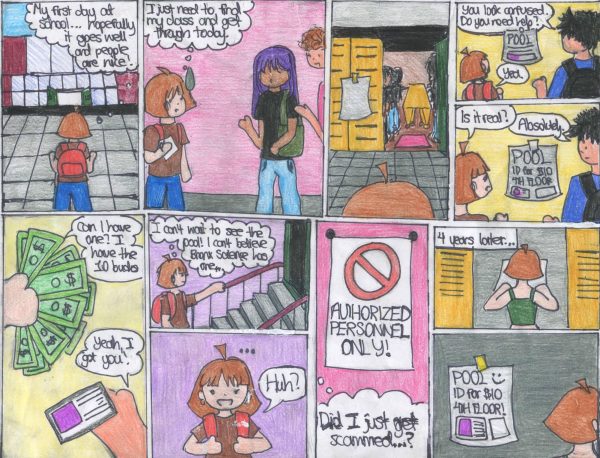

Under the influence of the question, he looked up towards the ceiling and then scrambled to search for a list of personality traits on Google.

After a few minutes, he responded, “I would say I care about others… I’m not too good at this. How would I describe myself?… Funny — sometimes… I don’t really know. I believe in the process is one of them. Give me one second. And the last thing would be that I — there’s no words. I really need to expand my vocabulary. That’s what I’m realizing now.” He soon added, “And I am positive.”

In defining his personality with me on the other end, he struggled with finding words that would be just right: “It’s hard to balance not sounding like you’re the worst human being in the world and also not sounding super full of yourself.”

Even in the quietest and darkest hour of the night, I still can’t grasp the adjectives that are “truest” to myself. I’m afraid if I prescribe myself a pleasant adjective, I’m forgoing my capability for much contradiction and evil. And I’m afraid if I give myself an undesirable adjective, I would be right.

“Do you think there’s such a thing as a ‘concrete personality’ or, at least, a temporary permanence?”

“Yeah, I would say probably. You could probably describe how someone was at one point in time. Describing someone currently is a lot more different. It’s definitely ever-changing. You don’t stay in one place for too long at all.”

“You’re in a dark room, which is great for figuring out yourself. How would you describe your personality to yourself?”

“What conclusions would I come to? Maybe that I worry too much about doing things rather than actually doing them. Is that in line with the question?”

“You can say anything.”

“And that I — I would say I virtue-signal a little bit even though that sounds bad. Sometimes, I present myself to others [in ways] different from my true self and present myself in different ways depending on who they are.”

“What is ‘the true self’ to you?”

Oliver thinks to himself for a bit in the way that Oliver does. “I guess the true self is what actions you take and, more importantly, why you take those actions. What is going through your mind when you have to make a decision? I guess. I think that’s the most important thing.”

There is much to be said for how others could disfigure the perception one has of themself. And it is often advised that only the singular person should have the keys to define themself. But what is the self without others there to influence it? Others’ influences do not leave when physical presences made their exits.

I consulted my guidance counselor Ms. Jacole Mills, and one of the school’s social workers, Ms. Danielle Heckman-Perez, and explained the range of thought I encountered. They both pointed to the awkward yet exploratory stage of development that all Bronx Science students are experiencing.

According to psychologist Erik Erikson’s theory of stages of psychosocial development, adolescents are battling between identity and role confusion, a period with the potential for much personal development and ideally provide a strong sense of self.

Confident in calling herself compassionate and quirky now, Ms. Mills recalled insecurities with her quirkiness when she was younger.

She said, “I’ve had these freckles on my face all my life. I’ve always been a little bit different. I’ve always sort of stood out from the group that I was in. It took a little while for me to be accustomed to it and to relish it and sit in it and like it and love it for what it is. It was difficult initially, but the last couple of decades have been okay.”

The conversation of personality easily slips into that of one’s broader identity. Ms. Mills recounted her childhood in Catholic school and her goal of becoming a nun established in her first year of high school. In the first year of college, this goal shifted to becoming a neurosurgeon.

She is clearly neither a nun nor a neurosurgeon, but she retains the practice of asking internal questions, a cornerstone in everyone’s process of perpetual change: “What will I do during retirement? How long do I want to work at a school? Do I want to go into private practice? Do I want to teach at a collegiate level?”

Ms. Heckman described herself as very outgoing, friendly, kind, generous, caring, fun-loving, and adventurous. Similar to Ms. Mills, she claimed her current confidence levels are much higher now than they were in high school; this was a quality she strengthened over time. She added, “You’re not supposed to have an answer at seventeen or eighteen years old. You’re still exploring. Getting older is not so bad.”

Dhinak Gaggenapally ’22, someone I’ve spoken to a moderate amount in school and on the bus home before the pandemic, soon challenged the Selina-Tobias Spectrum.

The question did not phase him. He pulled these four descriptors from a guidance counselor questionnaire: smart, passionate, inquisitive, and helpful.

Threatening the efficiency of any journalistic instinct in me, he asked, “Do you want me to elaborate?”

“Yes.”

“I’m not going to elaborate on smart. There’s no point. For passionate, I spend a lot of time looking at random things on the internet, and this ties into inquisitive too. When I set my sights on something, I either don’t give up on it, or I end up getting sidetracked with another thing I want to look at. Usually, when I decide to start doing something, I put a lot of focus and thought into it. For helpful, I like helping other people. I do it in a large variety of fields. I’ve done volunteering at the library, which is quite enjoyable. I’ve done helping random people online with things. It’s something I like,” he said with a startling calmness.

“Do you have any hesitancies or reservations before calling yourself all of these adjectives?”

“I’m pretty confident in who I am, so not really. I had to think about it a lot because, admittedly, I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about myself. I spend a lot of time thinking about other stuff. I didn’t really have any hesitations once I decided once I picked these adjectives.”

In a defeated attempt to find some sort of hole, any crack possible, I pressed, “But isn’t what you think about who you are?” That question, in retrospect, didn’t make much sense. Dhinak thinks a lot about programming, but he isn’t exactly a programming incarnate.

“I do believe that’s what I think about when I think about myself. I’m not lying to myself.” And this is the part when I begin to feel a bit surprised — that someone my age, who I’ve known for years could be so sure. I know I claimed in the beginning that I would be envious when I meet someone so sure of their personality, but all I felt was surprise. The Dhinak-Tobias Spectrum seemed more accurate of a measurement.

“Do you have any hesitancies with what you just said today?”

With an inscrutable face, Dhinak gave a firm head shake. I stifled a laugh.

Kathryn Le ’22, someone I had only known distantly through friends like Jillian, described herself as optimistic, a good reactor to stressful situations, supportive, and reliable, and she had all the reasons to justify it.

To support her claim of reliability, she noted her lack of procrastination. However, when she was asked if she had any hesitancies, she paused and reflected. She disclosed that procrastination does kick in when it is with a task she doesn’t like to do, a dreaded contradiction. She then concluded, “I think my personality has a lot of ‘sometimes.’ Sometimes I’m this way, but in other situations, I’m another way.”

And there comes that word again: sometimes. In response to the question, Zawad, my INFP twin mentioned before, said, “I — I don’t know. Sometimes, I’ll be serious when I need to. But most of the time when I’m with friends or people I’m comfortable with, I let loose. I don’t know anything else better than that.”

Sometimes. Sometimes, I’m the most generous person on this planet, and yes, I will carry your groceries to your house and plant too many poppies in this very fertile patch of land I found on my daily saunter across town. Sometimes, I feel the urge to detach the roots of all the flowers in the community garden from the soil one by one. Just sometimes, though. Because I hardly know what’s happening most of the time. And it all depends on where I am, who I’m with, and what’s going on.

Selina never just answered the question, often offering an unsolicited story to accompany it. Tobias stuck to answering the question and only the question, deviating only once to ask me what I like to read in reciprocation. Each of Oliver’s sentences was interspersed with a quick laugh, all of which I returned with an awkward smile. Even for me, the left side of my jaw perpetually leaned on knuckles.

Though I resonated with Tobias’ observations and would love for everyone’s personality to be amorphous, a suspicion clings to me: through a screen, I felt distinctive spirits and observed distinctive mannerisms of each person I talked to, meaning there has to be something, at the very least a slight consistency particular to each one of us.

I explained this “sometimes” to Ms. Heckman, and she made a point of differentiating between behavior and personality. Personality exists. Behavior is the sometimes that can be seen. For example, someone is extroverted, a personality trait. One’s extrovertedness may be exhibited in having minimal fear associated with initiating conversation, a behavior.

She placed herself in the school of thought that believes personality is innate, and aspects of that personality begin to reveal themselves when developing and grow more strongly as time goes on. She offered her seven-year-old daughter as an example: “Personality was there from day one. She is not straight. She has been the person she’s been since the day she was born.”

Thinking back to my conversation with Dhinak, I asked, “What are the factors that play into someone not being able to concretely define themself?”

“As you move along, maybe change the word concrete to finite. Personalities are just not finite. There are aspects that are pretty consistent, but again, it’s not a finite thing.”

At this moment, I went straight to the Oxford English Dictionary. I seemed to have forgotten what the word “finite” meant, which is to say this reframing had the foundations to displace much of my current thinking on personality. Even after I parsed over all the different definitions five times, I sat at my desk confused as to how Ms. Heckman made the jump from concrete to finite.

I think back now to Tobias and Jillian’s “one word” mentions and Oliver’s limited list of adjectives, and I see what Ms. Heckman is discussing is discovery. I see these adults speak with so much ease and confidence in their personalities and their changes as humans, and my first thought is to deny that this would ever happen to me. It’s something I can’t escape. Though I fear that time only passes to demand I relinquish something of mine, discovery about others in these conversations and within myself has already happened. This is irrevocable.

I should also say that I feel guilty that I have provided my reactions to their words and threaded these conversations together and, in that way, provided my conscious and subconscious evaluations. It contradicts the surprise I once expressed in the beginning. I’m not sure if an apology is necessary or if I should want to issue one, and I have no reconciliation for this except that I have pointed out the fact.

After all these conversations concluded and my confusion cemented, I headed downstairs for dinner. My younger brother and I grabbed chopsticks and scooped rice into our bowls. My parents and grandma got their soup from a tall pot. My family trickled one by one to our elevated dinner table and seated ourselves in assigned seats, which were more naturally established than written out in a rule book.

Once we resolved ourselves into our meals and the only sound to be heard was the drone of the air conditioner, I turned to my mom.

“How would you describe your personality?”

She was reading the daily news on her phone. As I stared at my mom, everyone else continued to eat. She looked up at me.

“I don’t know.”

She looked back down at her phone.

I asked my dad the same question. With a quick shake of his head, he responded, “I don’t know.”

It was my brother’s turn. “Fun.”

“Are you joking?”

My mom lifts her head and chimes in, “Fun? Really?”

My brother’s face turned red and scrunched up. “I think I’m fun.” He scampered over to the sink and deposited his empty bowl.

My mom asked my grandma the question in Taishanese.

My grandma looked me straight in the eye: “Uptight.”

“Anything else?”

“I don’t know.”

Even in the quietest and darkest hour of the night, I still can’t grasp the adjectives that are “truest” to myself. I’m afraid if I prescribe myself a pleasant adjective, I’m forgoing my capability for much contradiction and evil. And I’m afraid if I give myself an undesirable adjective, I would be right.

Cadence Chen is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She enjoys journalistic writing for its artistic concision and sharp insights. Cadence...