“I am Me, and I hope to become Me more and more,” wrote Paula Modersohn-Becker in a letter to her close friend Rainer Maria Rilke, following her split from her husband Otto Modersohn.

Such a landmark assertion of independence provides the backbone for the Neue Galerie’s new exhibition on Modersohn-Becker’s art, entitled ‘Paula Modersohn-Becker: Ich bin Ich / I am me.’

It also serves as a window into the artist’s own unshakable sense of self. Modersohn-Becker firmly believed that identity wasn’t binary, and that the bounds of her own personal identity – as a woman, as an artist, and as human – were limitless. Throughout her short life (she died at age 31), she worked passionately to explore the various facets of herself through her artwork.

Modersohn-Becker is well known in Germany, where she was the first woman to have her own museum. Yet she is little known in the United States, and the exhibition at the Neue Gallerie through September 9th, 2024 is her first blockbuster exhibition here, where it will then travel to the Art Institute of Chicago from October 12th, 2024 to January 12th, 2025.

Born in Dresden in 1876, Paula Modersohn Becker began painting at age 16 following a summer with English relatives. Coming of age in the late 19th century, she belonged to the first generation of female artists able to study at art academies and access professional training. Her parents allowed her access to a plethora of these opportunities to sharpen her talents, and this liberal upbringing helped to foster her firm conviction in equality for herself.

Modersohn-Becker was voracious, and she constantly sought new opportunities to grow and expand her skill. In 1895, impressed by an exhibition that she saw at the Bremen Kunsthalle, she joined the Worpswede artists colony in Northern Germany to continue her education. There, she met several figures that she would remain close to for the rest of her life, including Rilke, the sculptor Clara Westhoff, and her future husband Otto Modersohn.

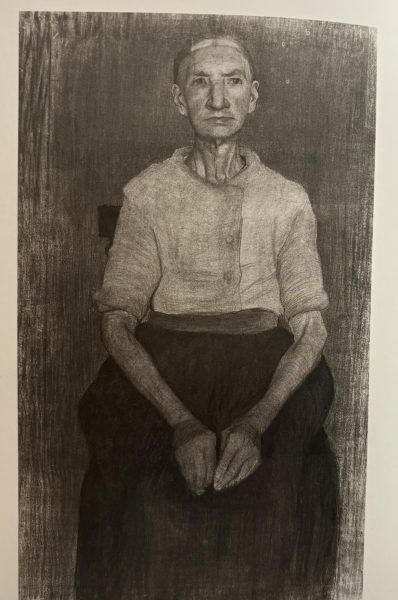

In her early days in the village, Modersohn-Becker largely produced drawings using charcoal, finding subjects in the young girls, women, and to a smaller extent, men, who lived in and around Worpswede. Rather than embellish her figures or create an idealized representation, Modersohn-Becker approached each subject with a sense of vulnerability and humanity. In fact, she made a point to emphasize the imperfections of each person: frown lines, bruises, bones, veins, wrinkles and more. In doing so, Modersohn-Becker sought to capture the various physical attributes that made their own identities distinct, just as she worked tirelessly to discern her own.

My favorite of these drawings is an 1899 piece entitled Farmers Wife, Seated. The central figure, an elderly woman of about 70, sits loosely on a chair as she stares unflinchingly at a point somewhere in the distance. Her loose dark skirt and blouse only serve to accentuate her jutting bones and angular features, but it is her wary expression that really stands out. While her eyes appear hard and unwelcoming, her posture and the curve of her mouth emphasize her sheer exhaustion. Sitting down to be drawn was perhaps a rare reprieve in a day of constant work, and her body inadvertently reflects the dueling relief and vigilance. While she appears grateful to be sitting, it is clear that she is unfamiliar with letting her guard down and allowing emotions to slip through the cracks.

Another drawing from around the same time, Standing Female Nude, depicts a naked pregnant woman from profile, head hung and belly protruding. Throughout her life, Modersohn-Becker had an interesting fascination with the idea of motherhood and pregnancy. Pregnant women are the subjects of many of her best known works, including Kneeling Girl with Stork, Self Portrait with Two Flowers, and Self Portrait on Sixth Wedding (Anniversary). Pregnancy seemed to terrify and excite her in equal measure; while she hungered to be a mother herself, she was deeply concerned that it would overshadow her budding career.

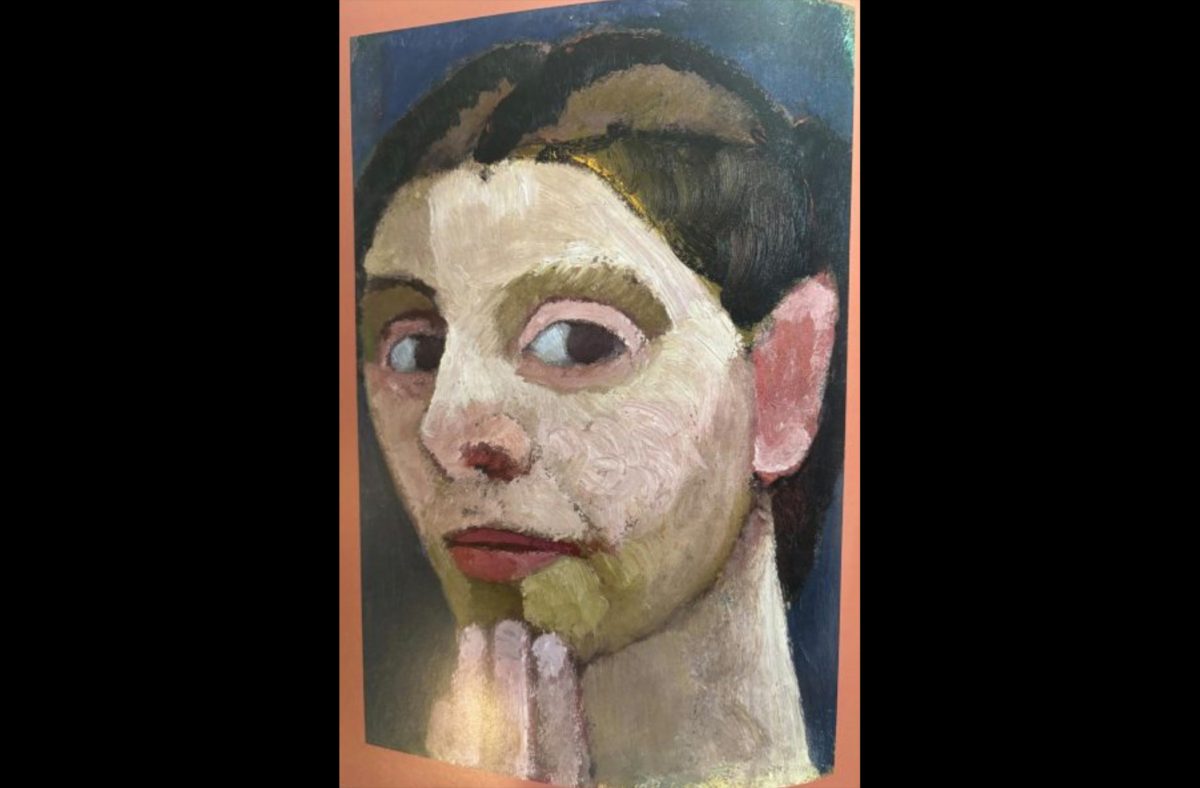

One of these nude paintings, Self Portrait on Sixth Wedding (Anniversary), is credited with being the first nude self portrait done by a woman. It is a bit of a contentious claim, for Modersohn- Becker is not entirely undressed in the painting (her lower body is covered), nor was she the first woman to paint herself topless. Yet the rich color and stark contrast to her previous works feels wholly unprecedented all the same.

The painting was made during a short period of independence, in which Modersohn-Becker left her husband behind in Worpswede and moved to Paris. It was the culmination of years of self-exploration, and although she ended up moving back to Worpswede a few months later due to lack of money, she described the time as “the most intensely happy period of my life.”

Separated from her husband and savoring her freedom, her self portrait was made at a time in her life when Modersohn-Becker least desired to be a mother. Instead, it presents the artist as an assured, confident creative person. In celebrating the double potency of women, she boldly asserted that she and her fellow female artists were capable of both childbirth and creation without sacrificing one or the other.

Interestingly, Modersohn-Becker had been a mother of sorts for much of her adult life, despite never becoming pregnant and having a biological child of her own. Her husband, Otto, had been married before and had a young infant daughter named Elsbeth, so Modersohn-Becker assumed the role of surrogate mother upon marriage.

Yet she seemed to be able to separate motherhood from pregnancy. Honorary motherhood was noble and achievable. Pregnancy, especially at a time where it could be so deadly for women, was uncharted and dangerous territory.

It seemed that these fears were legitimate, for 20 days after she gave birth to her daughter Matilde in 1907, she died of a postpartum embolism. Her dying words were, “What a pity.”

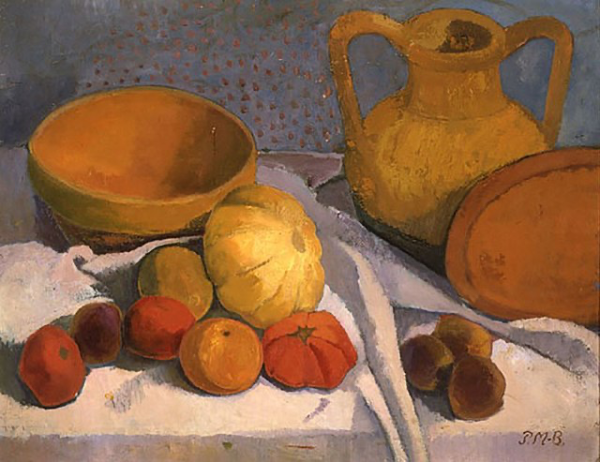

During her time in Paris, Modersohn-Becker became acquainted with the works of many of the era’s premier painters, including Auguste Rodin, Paul Cézanne and Paul Gaugin. Their work introduced her to the art of still life, and she quickly learned how to capture the “gentle vibration” of the various objects.

In these figurative works, she was repeatedly drawn to familiar motifs – jugs, oranges, flowers, and squash – placing a new emphasis on their intricacies. Many of these paintings are present in the Neue Galerie exhibition, including Still-Life with Fish, Still-Life with Clay Jug, Peonies, and Oranges And Still-Life with Yellow Bowl and Clay Pot. In emphasizing the imperfections, texture varieties and disheveled atmospheres of each object, Modersohn-Becker attempted to demonstrate that humanity wasn’t just bound to human subjects.

Interestingly, these pieces show a woman who is still deeply grappling with her sense of identity. Even decades into her career, Modersohn-Becker didn’t have a distinctive signature style, preferring to learn from those around her and to apply it with vigor.

The exhibit makes sure to highlight this never-ending rush towards discovery. Through 70 intensely vulnerable works, viewers get the sense that she was both insatiably curious and hardly ever satisfied. “The constant rush towards the goal is the most beautiful thing in life,” Paula Modersohn-Becker once wrote. Accomplishing a lifetime’s worth of work in a mere 31 years, it seems as if she knew deep down her own life would soon be cut tragically short.

Modersohn-Becker firmly believed that identity wasn’t binary, and that the bounds of her own personal identity – as a woman, as an artist, and as human – were limitless. Throughout her short life, she worked passionately to explore the various facets of herself through her artwork.