When James Baldwin arrived in Istanbul in October 1961, his writing career was at its breaking point. Another Country, still in its early stages, suffocated him. A book speaking to the nature of American loneliness, it was its very construction that pushed Baldwin away from his birth country and toward another.

Red-eyed and restless, he showed up unannounced at his friend Engin Cezzar’s doorstep. The two had met four years prior when Cezzar, a Turkish actor, played Giovanni in a screen adaptation of Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room.

“Welcome home, Jimmy,” said Cezzar, hosting a party at the time. After a bath and some conversation with the guests, Baldwin drifted off to sleep.

A few months later, he finished Another Country. Then, he wrote The Fire Next Time and, nine years later, No Name in the Street. Somewhat ironically, his most “American” works flourished in Istanbul, a place completely foreign and opposite from the unfolding civil rights movement in 1960s America. For the same reason, Baldwin’s Turkish decade is often described as the steadiest, most freeing time of his career.

“I can’t breathe,” he once told Zeynep Oral, a friend and fellow writer. “I have to look from the outside.” Thus began his time abroad, from Tel Aviv to Dakar to Saint Paul de Vence — each place making him more un-American and American at the same time.

Born in 1924, Baldwin grew up surrounded by the Harlem Renaissance and its literary leaders — from Langston Hughes to Countee Cullen — but considered himself a different kind of artist. Although his prose was poetic, he was not a poet. Following the steps of Cullen, his middle school French teacher, Baldwin explored Magpie, the literary magazine at Dewitt Clinton High School. From there on, he would begin to align himself with the narratives of racial, sexual, and moral conflict.

Throughout high school, Baldwin worked as a preacher at the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly, a religion he ultimately rejected but never fully left behind in his writing. One year after his high school graduation, in 1943, Baldwin opted to work various service jobs to support his family following the death of his father.

He continued to write, seeking the mentorship of Richard Wright. In Wright’s Fort Greene home, the two went over Baldwin’s early writings; while Wright helped Baldwin find a fellowship and publisher, Wright, more importantly, afforded Baldwin a place to explain his thoughts and the confidence to share them with the world.

Wright was perhaps most known for Native Son, his first published novel about an African American man and the systemic racism that surrounded his crimes. Selling over 200,000 copies in its first three weeks, its raw, grating descriptions of violence and anger astounded his intended audience of white Americans. But Baldwin denounced it as a “failed protest novel.”

Despite his initial praise, he began to publish several critiques of Wright’s work. In Notes of a Native Son, an aptly named 1955 essay collection, Baldwin described Wright’s words as a “fantastic and fearful image which we have lived with since the first slave fell beneath the lash.” Black intellectuals and critics believed his attacks to be too harsh, but he made no excuses; even when Wright confronted his criticism, he kept writing, even going as far as to call Native Son “gratuitously violent,” perpetuating dangerous stereotypes and ignorant of the traditions of Black life. In Baldwin’s mind, the Black identity was more than its struggle.

As he engaged with other writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Baldwin’s own career as a writer was yet to be fully realized. Over that decade, he had been working on Go Tell It on the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical novel about teenager John Grimes in 1930s Harlem and his relationship with family and religion, albeit with little success. It is his earliest published book that his ties to the church and Pentecostalism are most apparent, owing to his teenage experience as a preacher.

In fact, he opens Go Tell It on the Mountain with: “Everyone had always said that John would be a preacher when he grew up, just like his father.”

Closely modeled after Baldwin himself, John Grimes was born out of wedlock and never had the chance to know his biological father. Baldwin portrays John’s stepfather, also a preacher, as a key antagonist to John but attributes this relationship to their different upbringings and lack of mutual understanding. This dynamic serves as a microcosm of the church itself — an institution in the novel whose ideal is inconsistent with its reality, yet whose place in the characters’ lives remains significant, all-encompassing, and difficult to change.

“The Grimes believe the surest, and perhaps the only, weapon against destruction is the narrow way of the Lord,” author Ayana Mathis wrote in the New York Times. “John must follow this path, fully and resolutely.”

Mathis continued in the same essay that although Baldwin eventually left the church and its unyielding rigor, the community and pathos never left him. Still, with every new novel, his writing seemed to take on a more secular view of Blackness and homosexuality.

Baldwin’s 1961 trip to Istanbul had not been his first time abroad. Over a decade earlier, at age 24, he bought a one-way ticket to Paris with forty dollars in his pocket. There, against the backdrop of jazz clubs and gay bars, he finished Go Tell It on the Mountain and Notes of a Native Son from across the Atlantic.

It was also in Paris that he drafted Giovanni’s Room, perhaps his most widely acclaimed work of fiction. The novel, at only 159 pages, is a brutal, honest confrontation of sexuality, resistance, and the shame that accompanies the search for happiness. Unlike his previous works, every character in Giovanni’s Room is white — a move that raised questions about Baldwin’s role as an author. Should he, a Black man, be writing about white characters in a completely different environment than his own in America? Why was there no mention of race or racism in the novel?

The answer was simple: Baldwin refused to let critics close him into a box. He wouldn’t be just a Black or gay author, restricted to only writing about subject matters that affected him. In particular, Giovanni’s Room tackled homosexuality so candidly and fully that “there was no room in the novel for race.”

“[T]his novel is a personal triumph for Baldwin, as it shows he had the capacity to think outside of his station, to dream of a world where race was only a word, and he could instead focus on demonstrating the tragedy of a love not pursued,” wrote Santiago Eastman Herrera in a 2023 review.

At first, no publisher wanted the piece. Giovanni’s Room tells the story of David and Giovanni, the entanglement between an American and an Italian man living in post-WWII Paris. It is often described as a “tormented love affair,” circling around secrecy and different ideas of what love should be. It’s easy to let the book’s content define the prejudice and alienation it received at the time, given today’s changed attitudes around gender and sexuality. But simply looking at the subject matter itself can be too limiting.

Giovanni’s Room, with all its complexity, has its flaws. Although it centers around two men, Baldwin introduces Hella, the only female character in the novel, before Giovanni. Unconventionally yet consciously feminine, she remains unexplored. By relying on David’s depictions of her as passive, or the “poor soft-headed thing that she is,” Baldwin creates a tendency for readers to view Hella as “a part of the heteronormative order that David struggles against, or to a victim of David’s refusal to take responsibility for his gender identity,” argued Betty He for the Stanford Caesura, a literature research journal. In other words, she becomes reduced to a plot device.

Paris was ever-present in Giovanni’s Room, looming behind its characters and Baldwin himself. The city came to be something bigger than its queer nightclubs or broad boulevards: it was simultaneously freeing and isolating. As Baldwin’s disputes with Wright worsened, he decided to look elsewhere. Paris was no longer home.

Istanbul became that elsewhere. As Eddie S. Glaude Jr. puts it, Baldwin’s elsewhere didn’t have a name: it was simply “a physical or metaphorical place that affords the space to breathe, to refuse adjustment and accommodation to the demands of society, and to live apart, if just for a time, from the deadly assumptions that threaten to smother.” Glaude, a professor of African American studies at Princeton University, went on to describe Istanbul as Baldwin’s escape from the “American lie.”

There, Baldwin finished Another Country, this time centered around interracial and extramarital relations. Nothing about it is simple: the main character, Rufus, is portrayed as abusive of his partner, Leona, and wholly responsible for her eventual time in a mental institution. He commits suicide after the first chapter and for the rest of the novel, his friends and mentors grapple with his death while navigating their own relationships, none of them any less complex.

“It’s really a book about the nature of American loneliness and how dangerous that is,” explained Baldwin in a 1962 interview. “How hard it is here for people to establish any real communion with each other and the chances they have to take in order to do it.”

For this reason, Another Country pioneered the exploration of race relations through love and marriage. The novel’s relationships, continually hindered by internalized racism, represent a microcosm of the racial power struggle and the violence that came with it. The title is both a question and a fantasy: as author Stefanie Dunning wrote in 2001, “another nation, in which our racial and sexual selves are imagined and defined differently or perhaps where they are not defined at all… another country, a mythic, imaginary and unattainable place where relationships are not fractured by difference.”

Baldwin’s true genius, though, shines not in his prose but in his view of the world — literary critic Mario Puzo had similar sentiments in his 1968 review of Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone. “Baldwin’s greatest weakness as a novelist is his selection or creation of incident,” he said. “It becomes clearer with each book he publishes that Baldwin’s reputation is justified by his essays rather than his fiction.”

In The Fire Next Time, his best-selling book, Baldwin combines personal reflection with social commentary in a series of essays. In the collection’s first essay, A Letter to My Nephew, he pleads and demands a more hopeful, integrated future. With eloquent fury, he displays a rare kind of understanding for his oppressors: “Many of them indeed know better,” he advised his nephew, James, who carries his namesake. “But as you will discover, people find it very difficult to act on what they know.”

He participated in civil rights protests, but as a writer and journalist, he took on the role of changing mindsets through language. Instead of immediately tackling the difficulties of integration, Baldwin knew it was necessary to understand why integration was so difficult. Otherwise, true to the book’s title, there will be a “fire next time.”

Similar to the themes in Giovanni’s Room and Another Country, Baldwin implores his audience to love themselves and each other; in a world with so much violence and adversity, he holds an eye for the beauty in things. He lived knowing that, just like the characters in his books, he and the people around him are complex — never only black or white, often falling into the gray.

In 1970, Baldwin returned to France, this time in Saint Paul de Vence, near Nice and France’s southeastern region. Once again, he sought distance from America and its criticism: he believed the government had subjected him to surveillance, and fellow members of the civil rights movement rebuked him for his homosexuality.

He published If Beale Street Could Talk in 1974 and Just Above My Head in 1979, both novels containing sharp insight distinctive to his literary style. In 1985, he published his final work: The Price of the Ticket, an anthology of autobiographical writings beginning in 1948. In a New York Times review published the same year, journalist Salim Muwakkil described the essays as “enlightening, entertaining and, because of his remarkable prescience, a bit eerie.”

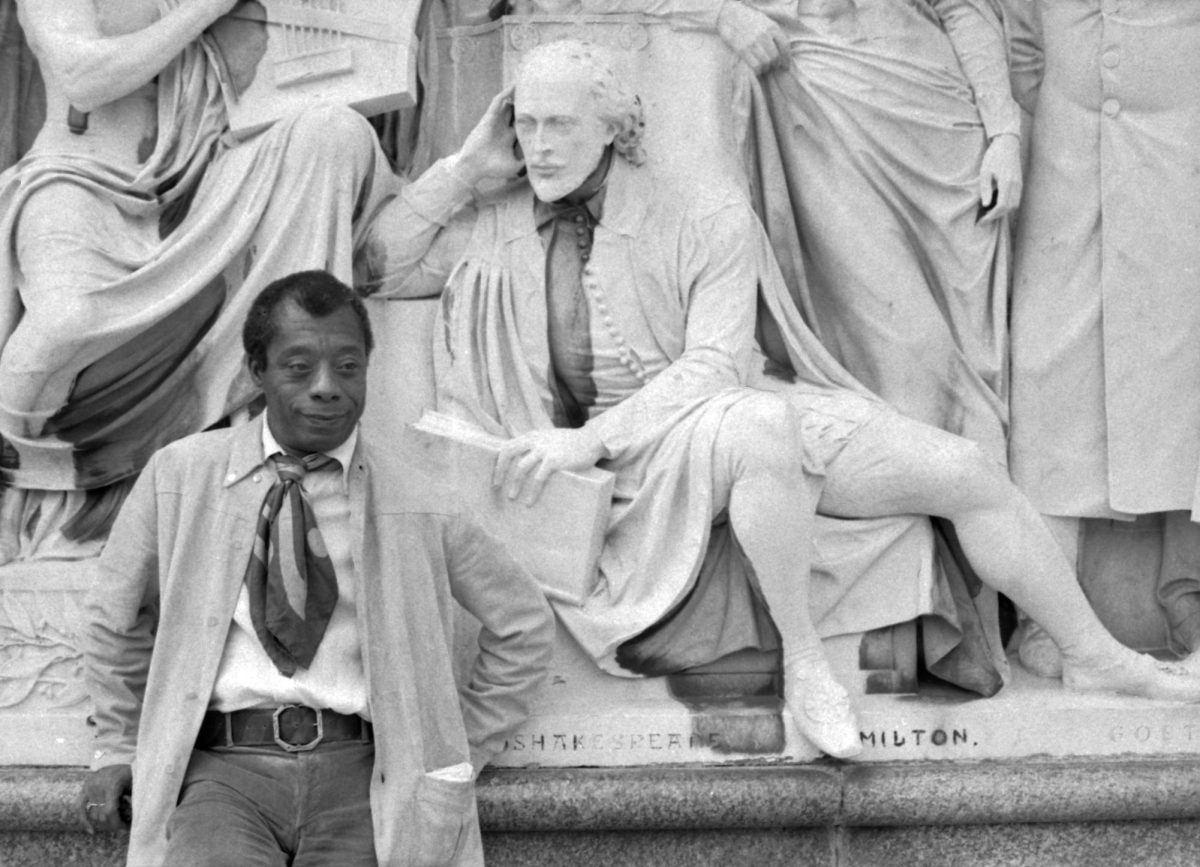

Two years later, Baldwin passed away in his home in Saint Paul de Vence after a long battle with stomach cancer. Throughout his life, France — along with Istanbul and his other homes abroad — served as a refuge far from the subject matters of his books. Even in death, he surpasses boundaries: as both an activist and stylist of the Black identity, James Baldwin dared to write, think, and live openly.

“[Giovanni’s Room] is a personal triumph for Baldwin, as it shows he had the capacity to think outside of his station, to dream of a world where race was only a word, and he could instead focus on demonstrating the tragedy of a love not pursued,” wrote Santiago Eastman Herrera in a 2023 review.