The Austrian artist and the “premier painter of woman” Gustav Klimt had a unique fondness for the Austrian countryside. Beginning in the 1890s, he spent his summers vacationing off the coast of the picturesque Attersee lake, partaking in afternoon swims, boating trips, and leisurely walks in the village, all in an attempt to capture each bit of the landscape.

Klimt began visiting Attersee at a turning point in his career. He had achieved admirable success with large scale public commissions, yet persistent attacks from high-profile critics fueled his resolve to paint for personal satisfaction alone.

To Klimt’s delight, his tiny refuge proved to be the perfect muse. He obsessively documented Attersee on paper, drawing everything from the village’s crumbling chapels, to the eerie woodland forests, and even the vibrant flowers surrounding his countryside home.

Back in Vienna, Klimt began to experiment with gold leaf, resulting in a series of masterpieces that feature ethereal figures blended into their shiny gold backgrounds. Their crown jewel was the 1907 Portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer I, a depiction of one of Klimt’s most fervent collectors that is as delicate as it is statuesque. The painting now serves as the centerpiece of the Neue Galerie’s permanent Klimt collection, which also includes the unfinished Portrait of Ria Munk III and Pale Face.

Standing at the corner of 5th Avenue and 86th Street, in Manhattan the Neue Galerie has long been a haven for Austrian and German artwork since it was established in 2001. It is a more intimate alternative to the Metropolitan Museum of Art mere blocks away, though just as popular amongst visitors and New York natives alike, evidenced by the frequent 30-40 minute line to simply make it inside.

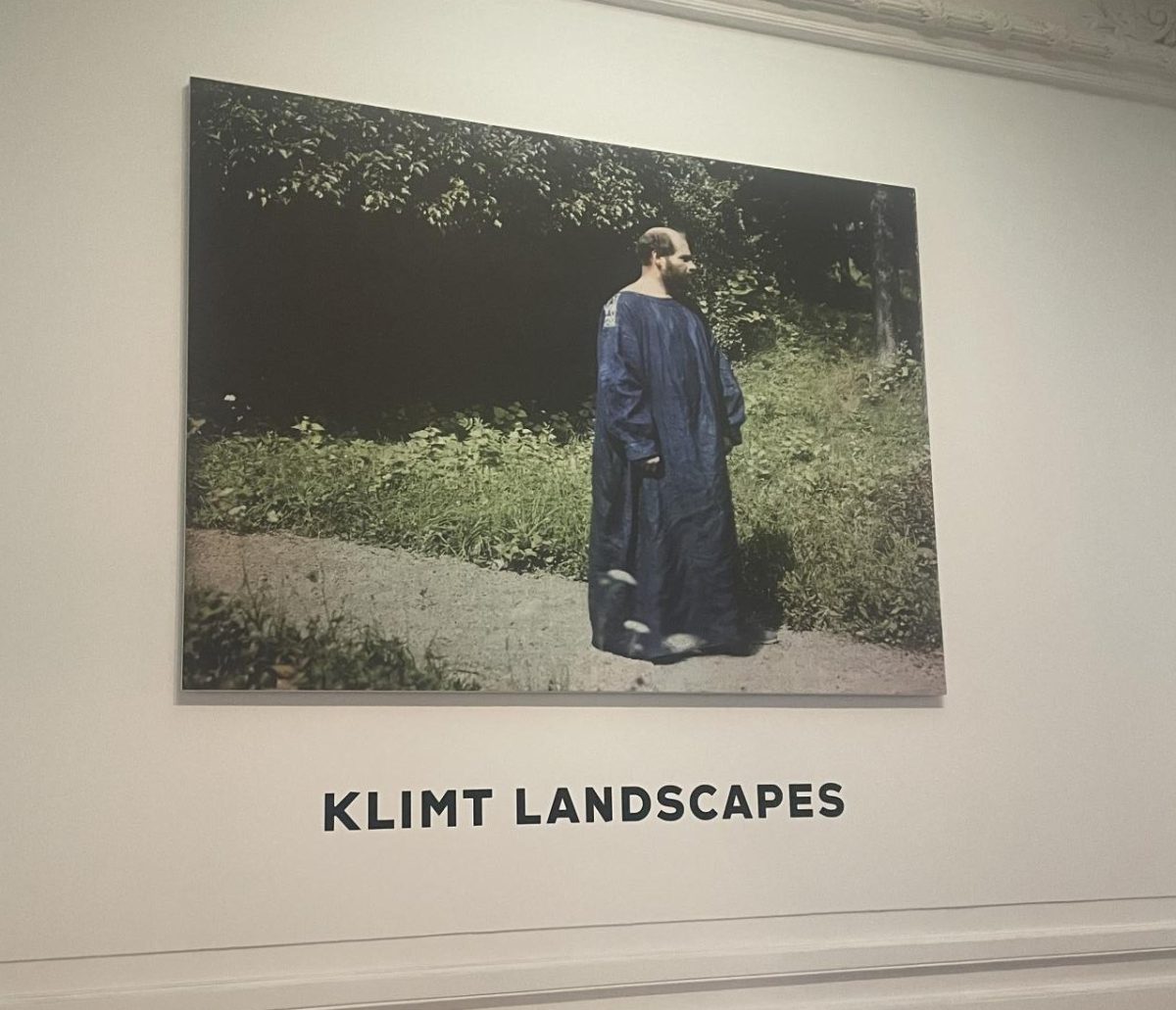

On a cold March afternoon, after waiting in one such endless line, I finally made it up the winding staircase and to the third floor, where the ‘Klimt Landscapes’ exhibit was being housed. (Tickets can be purchased through May 6th, 2024 HERE).

Whilst the title implies a plethora of paintings, in actuality, the Neue’s exhibition only contains five landscapes made during his time in Attersee, as well as an additional five non-landscapes, significantly less than Klimt’s first dedicated landscape show at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown in 2002.

Initially, the Neue Galerie had planned on having many more paintings as a part of the exhibit, as evidenced by the paintings in the catalog for the exhibit. One can speculate that worldwide instability, brought about by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the war in Ukraine among other things, led many European museums to rescind permission to allow their Klimt paintings to travel to the U.S. In the end, only the National Gallery Prague lent paintings to the Neue Galerie for this exhibit.

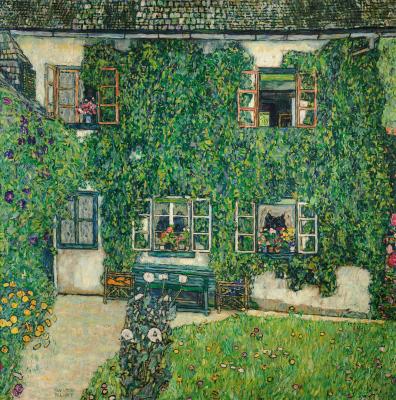

These remaining pieces are spread throughout three rooms, Seurat-like in their intensity, bursting with shades of green that seem to press out of the canvas. Each tree and brush is composed of thousands of tiny dots and dashes, careless strokes that give a wild aspect to the seemingly pristine landscape.

They are a far cry from Klimt’s traditional style of portraiture, and yet elements of his aesthetic can still be found in the elaborate mosaic pattern of the trunks, and the geometric lining of the buildings. Further analysis of the works also reveal the hints of vibrant pigment expected of a Klimt: pink flowers in a windowsill in Forester’s House in Weissenbach II (Garden), and light yellow pears amongst a mass of green leaves in Pear Trees.

The paintings exude a type of magnified Pointillism, a hybrid take on the era’s most dominant style, yet the registers of color Klimt creates also find analogies with various Modern artists, including Hans Hoffmann, Piet Mondrian and even Mark Rothko.

With such an intense spotlight on such few works of art, one would expect the paintings shown to be exemplary, and yet to many, the endless canvases of green veer into mediocrity in comparison with his other works, sickly sweet in their sentimentality.

But while this may be true at a quick glance, a significant time spent analyzing the exhibition tells a different story. For the real beauty of ‘Klimt Landscapes’ doesn’t lie in the canvases, but in the countless objects that flank them, painting a picture of Klimt’s life in the countryside that extends far beyond Attersee’s vines or villas.

Drawn primarily from the Neue Gallerie’s own holdings, the eclectic collection of mementoes range from original family photographs to Klimt reproductions, Wiener Werkstätte jewelry, and 19th century evening attire. Unremarkable on their own, together they paint a unique picture of Gustav Klimt the man, not just Gustav Klimt the artist.

In particular, the objects help shed light on Klimt’s relationship with Emile Flöge, the sister of his brother’s wife Helene, and a longtime muse, collaborator, and friend. Together, Flöge and her sisters formed Schwestern Flöge, a fashion-forward design store that catered to the Viennese upper echelon. Many furnishings from the Flöge sister’s shop are present in the exhibition, the highlight being an original Reform dress, the novel garment designed by Flöge that ushered in a more radical era of women’s dress.

Not just limited to dress or jewelry, Flöge’s presence can also be felt on the walls, specifically in a collotype of Klimt’s 1903 Portrait of Emile Flöge. The painting was one of Klimt’s earliest decorative portraits, which he later reworked, adding a brush of silver and sharpening the vivid blue pigment. Interestingly enough, the collotype in the Neue is from before the amelioration, giving us an uninterrupted view of Klimt’s early artistic instinct and unfettered mind.

Flöge’s piece is actually only one out of 26 collotype photographs from the collection “Das Werk von Gustav Klimt” that can be seen at the exhibition, divided amongst the three galleries. They fill up the wall space between each late landscape, a silent narrative of Klimt’s artistry and evolution. Though the exhibition centers around landscapes, the collotypes vary in topic and medium, exemplified by the placement of famed figurative work The Kiss collotype next to Sunflower in gallery two.

In ‘Klimt Landscapes,’ photography is everywhere, on the walls, but also in the art pieces themselves. Klimt ran in the same circles as many members of the famed Vienna Camera Club, including Heinrich Kühn and Hugo Henneberg, and an intimate exposure to their creative process influenced his paintings deeply. Their pictures made the Viennese landscape look like it had been rendered in oil paint, and Klimt worked to integrate the aesthetic onto canvas.

This is best shown in his 1900 painting The Large Poplar Tree II, included in the exhibition, where the landscape almost blurs like that of a photograph, fuzzy and impressionist like. A mass of black and green stands imposingly in the background – the poplar tree – a stark contrast against the otherwise serene countryside.

The finished ‘Klimt Landscapes’ exhibit is not what it set out to be. Yet despite the lack of formal paintings, the exhibition is not a disappointment. Gustav Klimt, known to the art world as many things, is not often considered a landscape artist, making the numerous objects from his life in Attersee engaging as opposed to redundant.

I doubt there will ever be another Klimt exhibition as eye opening as this one, concerned with not just the paintings on the wall, but the man behind the canvas. Everyone, from Klimt superfans to first time viewers, will be utterly awed by the dizzying array of new information at their fingertips. I know I was.

For the real beauty of ‘Klimt Landscapes’ doesn’t lie in the canvases, but in the countless objects that flank them, painting a picture of Klimt’s life in the countryside that extends far beyond Attersee’s vines or villas.