- “Beckmann is not a very nice man.

- Beckmann had the bad luck not to have been endowed by nature with a moneymaking talent, but rather with a talent for painting.

- Beckmann is hardworking.

- Beckmann loves Bach, Pelikan, Piper, and two or three other Germans.

- Beckmann is wild about Mozart.

- Beckmann suffers from an unshakable weakness for that faulty invention ‘life.’ The new theory that the earth’s atmosphere is surrounded by a massive shell of frozen nitrogen gives him cause for concern.

- Beckmann still sleeps very well.”

The German painter Max Beckmann wrote these words as an autobiographical self-portrait in 1924. They have been translated and reprinted in the book Max Beckmann: Self-Portrait in Words, translated by Barbara Copeland Buenger, Reinhold Heller, and David Britt. Beckmann was an intense person who explored the deep traumas people faced during the periods of World War I and the Weimar Republic.

(Isabel Goldfarb)

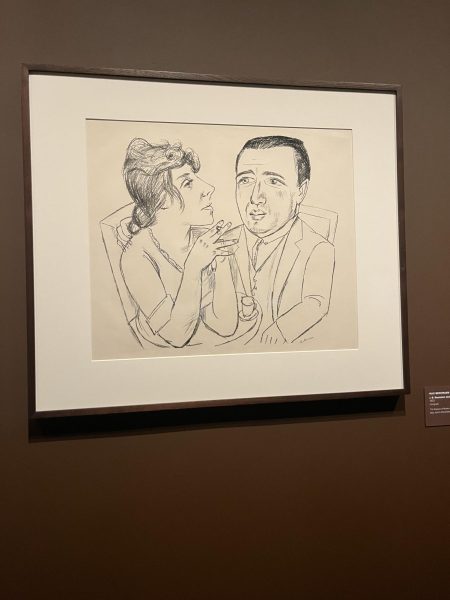

An exhibition entitled ‘Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925,’ currently on view through January 15th, 2024 at the Neue Galerie (located at 86th Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan), explores Max Beckmann’s unique and impressive artworks. The exhibit provides a deep dive into Beckmann’s dark and critical views of humanity by spotlighting the shift occurring in Beckmann’s works during this decade. The exhibit showcases around 100 of the artist’s works including paintings, drawings, and significant print portfolios.

Max Beckmann’s work, characterized by its profound emotional intensity, illuminates the darker aspects of human nature.

The curation of the exhibition was overseen by Dr. Olaf Peters, a Professor at Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg in Germany. Dr. Peters is a long time partner with the Neue Galerie, having previously organized numerous exhibitions for them.

In ‘Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925,’ Dr. Peters showcases an opportunity for visitors to experience the evolution of Beckmann’s art. By examining the work’s display, viewers can appreciate the nuances of Beckmann’s rollercoaster ride of a life, gaining insights into the mind of this artist.

As visitors navigate through the exhibition, they encounter sections dedicated to periods throughout Beckmann’s life: ‘Portraiture and the Self-Portrait,’ ‘Religious Paintings,’ ‘Allegory,’ ‘Still-Lifes,’ ‘Landscapes,’ and the burgeoning ‘Social Life in early Weimar Germany.’ Each section works together to show how Beckmann’s art mirrored the time in which he lived.

Within the gallery’s walls, the dramatic transition in Beckman’s work is portrayed — his artistic realism of the Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. This transformation is a central theme of the exhibition, highlighting Beckmann’s shift in style, subject matter, and outlook.

A pivotal moment that influenced Beckmann’s artistic transformation was his personal involvement in World War I. As the war began, Beckmann served initially as a volunteer nurse in East Prussia in 1914. Beckmann’s short-lived but impactful stint at the frontlines profoundly affected his perceptions of life and death – themes that would be displayed on canvas.

In a letter to his wife Minna Beckmann-Tube, from October 1914, which appears translated in the exhibition’s wall copy, Beckmann wrote, “…my will to live is for the moment stronger than ever, even though I have already experienced dreadful things and died myself with them several times. Yet the more one dies, the more intensely one lives. I have been drawing to protect one from death and danger.” This letter provides a window into Beckmann’s tragic outlook on life.

Despite only briefly being on the frontlines, Beckmann continued to serve during the war as a medical orderly in Belgium the following year. However, the horrors and the relentless pressure of the wartime experience eventually took its toll on him. In July 1915, he suffered a nervous breakdown and received his discharge from service in 1917, returning home to Frankfurt for recovery.

In September 1918, Beckmann authored a text entitled ‘Creative Credo,’ outlining his artistic stance during the dark times of war.

“I intend to be a part of all the misery that is coming,” he wrote, signaling his commitment to engage with and reflect upon the societal upheavals of his time. Yet, within all of his misery, Beckmann shows a deep love for other people through his ability to depict humans realistically and not as idealized figures. .

‘Creative Credo’ is a significant part of the Neue Galerie exhibition, serving as a manifesto that offers profound insight into Beckmann’s artistic philosophy. Beckmann’s experiences in the war carefully shape his early work, which is explored in the section entitled “Portraiture and the Self-Portrait.”

(Isabel Goldfarb)

Beckmann had a strong interest in painting faces, which is evident in his numerous portraits and self-portraits. His ability to convey complex emotional states through different expressions and poses is what he is known for today. Often, his subjects appear vulnerable, nude, and even covered in blood. His self-portraits are particularly notable for their unsettling nature, often reflecting his own existential struggles and responses to the unstable times he lived through.

Beckmann’s portraits, with their dark and disturbing presence, are intricately placed against a black wall in a small room, giving viewers a sense of enclosure. The Neue Galerie is known for its exhibits using vibrant wall colors and the juxtaposition of art with these colorful backgrounds. Different color palettes amongst the Neue Galerie’s exhibition design and Beckmann’s art heavily contributes to one’s experience as you feel your emotions change as you explore the exhibit.

As he healed from the war, Beckmann’s artistic pursuits began to change. The romantic and painterly compositions gave way to more angular forms. His palette underwent a transformation as well, adopting darker tones with subdued brushstrokes. Moreover, the subject matter of his pieces evolved, shifting from historical painting to more contemporary themes, often viewed through a Biblical lens.

Post-war, his canvases began to engage more with subjects that were intense and often violent. In the 1920s, the Weimar Republic had come to power and Germany was experiencing a time of intense hyperinflation, poverty, and economic insecurity. Beckmann took on depicting themes of political intolerance as well as the realities of poverty and social injustice.

Despite this political chaos of the time, Beckmann’s art retains an element of spirituality, as his art often depicted traditional Christian iconography, as his subjects were shown to be experiencing raw pain and brutality.

The paintings and drawings featured here capture the spirit of the period, providing a window into the complexities of life during this dark time. Visitors will see Beckmann’s critical eye and his ability to capture the harsh truths of humanity, from the lavish parties of the upper classes to the meager and humble lives of those on the margins.

‘Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925’ offers an in depth exploration of Beckmann’s life, providing valuable insights into his artistic development and the historical context in which he worked. Visitors leave with a deep understanding of Max Beckmann, as well as a sense of the profound impact of art on understanding history and humanity.

In ‘Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925,’ Dr. Peters, the curator of the exhibit, showcases an opportunity for visitors to experience the evolution of Beckmann’s art. By examining the works on display, viewers can appreciate the nuances of Beckmann’s rollercoaster ride of a life, gaining insights into the mind of this unique artist.