William Blake: In Search Of Wonder

William Blake was a Romantic visionary who promoted philosophical and mystical undercurrents of individuality, imagination, and freedom throughout his life and in his oeuvre of prophetic artworks.

Thomas Phillips, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

William Blake (1757 – 1827) was a Romantic visionary who promoted the human imagination in his lifetime and inhis oeuvre of otherworldly artworks, considering them to be “the Body of God.” Blake’s philosophy of life can be summarized in one crucial insight: we don’t live in reality, we live in what we think reality is. If there is an essence to human existence, for Blake, it is the divine spark of the human imagination.

Born in 1757, William Blake was an English poet and painter whose work gives us a glimpse into a world of wonder. In his lifetime, his art was ignored or dismissed, and few people took his ideas seriously. He was largely seen as a madman or lunatic. Today, Blake is recognized as the most spiritual of artists, and the central figure in the pursuit of imaginative thought. While most artists sought to realize art from the external world of reality, Blake pursued the inner world of dreams, visions, and imaginations.

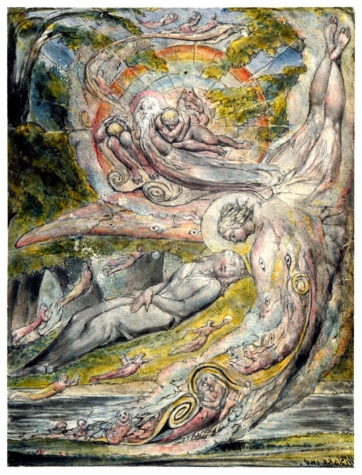

Blake’s mystical experiences would lead him on a spiritual journey that was the exploration of his inner self. He was a zealous advocate for the use of imagination over reason in the creation of poetry and images. He believed that the ideal forms of art, a concept going back to Plato’s theory of forms, were not to be constructed from observations of nature, but from visions originating in oneself. Blake’s philosophy of life can be summed up in one crucial insight: we don’t live in reality, we live in what we think reality is. Therefore, Blake was driven to enable others to apprehend the phantasmagoria of sights he treasured. In one of his epic poems, Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion (1804-20), he declared:

“…I rest not from my great task!

To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes

Of man…”

Blake was, in many respects, a pioneer of his time. He opposed slavery, racism, tyranny, and all forms of authority, including the established church, politicians and monarchies. He criticized the Industrial Revolution for turning people into machines, alienating them from nature, human relationships, imagination, and God. Blake saw how Christianity, with the message of love and brotherhood, had become corrupted into the source of social control, spreading fear and resentment into society’s way of life. Instead, Blake believed in the emancipation and freedom of the human spirit. To do so, he sought a spiritual truth, one acquired only through introspection.

It is here that we recognize the conviction upon which Blake bet his life: the only way to be freed from our oppression is to go beyond it through imagination. When coupled with creative skill and compelling thought, the imaginative mind reveals the true wonders of life. It converts everyday incidents into rich perceptions that amount to revolutionary experiences. It highlighted Blake’s significance as a thinker and visionary. And it promised the gift of the fourfold vision, a feel for which can be gained by considering what spectacles it allowed Blake to perceive in the world around him. If there is an essence to human existence, for Blake, it is the divine spark of the human imagination.

Beginnings Of Blake

Blake’s childhood set the cracks of dawn to the revolution he espoused later in his life. Unlike many well-known writers of his day, Blake was born into a family of moderate wealth. As a young boy, he wandered the streets of London and could easily escape to the countryside. Blake skipped formal schooling at the age of 10 in favor of being homeschooled by his parents. In later years, he would praise this decision:

“Thank God, I never was sent to school

To be flogged into following the style of a fool!”

Blake was surrounded by literature from a young age. He frequently read the works of Shakespeare, Milton, and Dante. The Bible in particular had a profound influence on Blake, and the book remained a source of inspiration throughout his life. Its prophetic and apocalyptic imagery stirred his mind. The child Blake experienced his first vision while sauntering along Peckham Rye. He looked up and saw, “A tree filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars.” Another time, Blake was aghast to see God put his head to the window, which sent the boy screaming. From the beginning, Blake was struck with a beaming spirit.

Blake’s artistic ability became evident to his parents, so they sent him to a drawing school at the age of 10. There, he became enchanted by the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. Two years later, Blake began writing poetry. When the expenses of art school proved too costly, Blake became an apprentice to engraver James Basire. For seven years, Blake created illustrations of the works of other artists, receiving a small sum of money in return.

Blake was deeply affected by an incident at around this time. In June of 1780, riots broke out throughout London incited by the anti-Catholic preachings of Lord George Gordon and by resistance to continued war against the newly declared American nation. Houses, churches, and prisons were burned by uncontrollable mobs bent on destruction. One day, as Blake was walking towards Basire’s shop, whether by design or by accident, he found himself at the front of the mob that stormed Newgate prison. The images of violent destruction, unbridled revolution, and sudden transformation lodged into Blake’s mind, which would become recurring themes in his later works.

Following his apprenticeship, Blake attended the Royal Academy of Arts in London, but swiftly dropped out as he felt that his imagination was weakened by academia, and his teachers showed little interest in his work. Blake chose to follow his imaginative mind, a path emboldened by his vision, while making a modest living from illustrating books, giving drawing lessons, and engraving designs from other artists.

In 1781, while Blake recounted the story of heartbreak after a rejected marriage proposal, a woman by the name of Catherine Boucher listened and pitied him from her heart. Blake asked her, “Do you pity me?” When she responded affirmatively, he declared, “Then I love you.” The couple married and began their lifelong relationship. Blake taught Catherine how to read and write, skills which few women of that time engaged with. She proved to be an invaluable partner for Blake and supported him in his visions as well as helping with his art.

Perhaps one of Blake’s most traumatizing memories took place in 1787, with the death of his younger brother Robert, Blake’s dearest family member. He tended Robert in his illness, remaining close by his side for a grueling fortnight. As Robert drew his last breath, Blake remembers seeing his brother’s spirit ascend heavenward, “clapping his hands for joy.” Following the episode, Blake’s exhaustion put him to an unbroken slumber for three nights. But Robert never truly left Blake. Robert’s spirit continued to visit his brother in his imaginations. A sense of reality expanding, it must have deeply moved Blake’s psyche. In a letter to William Hayley, Blake wrote:

“I know that our deceased friends are more really with us than when they were apparent to our mortal part. Thirteen years ago I lost a brother, and with his spirit I converse daily and hourly in the spirit, and see him in my remembrance, in the region of my imagination. I hear his advice, and even now write from his dictate.”

Four Petals of a Blooming Vision

In his poetry, Blake describes four states of being that correspond to different attitudes towards imagination, and therefore experience the world in contrasting ways. By recognizing which state a person or society finds themselves in, it’s possible to become more capable of understanding, embracing, and entering the others. He gave these states names: Ulro, Generation, Beulah, and Eternity. They offer important beacons of solace on the quest of following Blake: if you seek the grail of the fourfold vision, it’s essential to have a feel for how each petal of his vision unravels. In a letter to Thomas Butts, his leading patron, Blake wrote:

“Now I a fourfold vision see,

And a fourfold vision is given to me;

‘Tis fourfold in my supreme delight

And threefold in soft Beulah’s night

And twofold Always. May God us keep

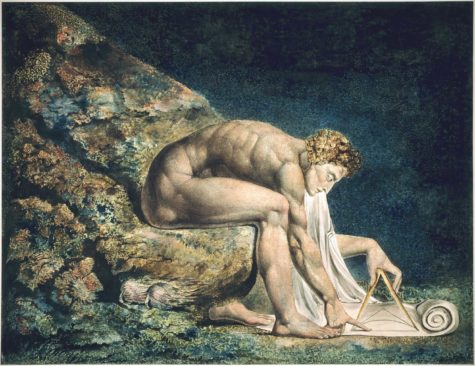

From Single vision & Newton’s sleep!”

To Blake, Newton represents the epitome of what he saw change in the world through the Age of Enlightenment. The industrial age was booming, manifesting the insights of the scientific revolution. Society became increasingly fixated on the physical aspects of reality, and the inner world by rational thinking. Rational empiricism was the philosophy that looked to the material world for evidence of God’s existence. Today, we know this philosophy mostly through its modern successor, the scientific method, which seeks to gain a systematic understanding of the world through experimentation and analysis.

Blake calls this Ulro, single vision, the world as observed in a cold, unimaginative way. Here, there’s no room for subjectivity. While claiming to study reality, its imagination is gripped by the material world alone, it isolates itself from reality. This is the poorest of Blake’s visions, where we rely purely on our concrete physical senses. However, there are many more experiences beyond that. In his book The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790), Blake wrote:

“If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.”

Blake’s idea of the Fall is different from that found in Christianity, which understands the fall of man as Adam and Eve’s primordial sin of eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge. Blake understands the Fall as caused by us human beings, by Ulro’s lack of imaginative freedom. It is a mentality that has become highly prevalent in our age. Life is organized around faceless metrics such as the work schedule, social media analytics, and personal wealth. Yet, it’s never quite clear what these seeming benefits are for, with the outcome that people and societies fall stricken with Ulro’s ‘dull round,’ as Blake phrases it.

Many people live haunted by the fear that something has gone inextricably wrong and their life lacks meaning. From Blake’s point of view, this is because the human imagination has swung into reverse. Unconsciously, single vision works to discount what he called the ‘minute particulars’ that bear the real fruits of life, preferring instead an existence described in generalizations and statistics. Ulro doesn’t have much to say about crucial experiences of life such as suffering and death, beyond saying that they must be the meaningless byproducts of natural processes. That itself compounds the suffering, producing “a weary Life, in brooding cares and anxious labours, that prove but chaff.” So, as the crisis deepens, the shortcomings of Ulro’s mind can be emphasized, which prompts a shift of consciousness, to the next state of mind Blake called Generation.

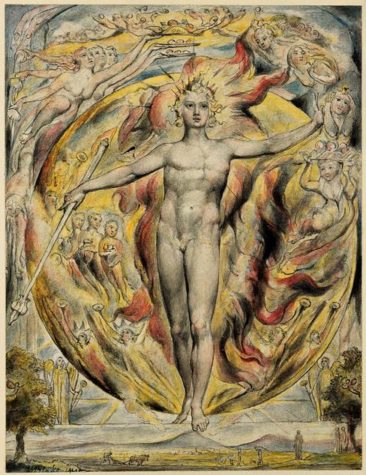

Generation, or twofold vision, is that of subjectivity and imagination — this is how Blake perceives the world always. It is to play with fantasy, like looking at the morning sky and seeing angelic forms rise with the Sun. With regards to the Sun, people in Generation will eagerly remark that they are made up of the ashes of stars, acknowledging that, in celestial nuclear furnaces, stars like the Sun forge the building blocks of life, such as carbon. They will discuss the many ways in which an average star like our Sun is about right for the emergence of biological life and even wonder at that fact. Generation is a mental upgrade to the appreciation of the universe.

To the untrained eye, however, it will seem like the ploy of a fanciful mind to expect the Sun to look like anything but a golden disk in the sky. But Blake could see more because he realized that he saw the world not with the eyes, but through them. In his unfinished poem The Everlasting Gospel (1818), Generation is contrasted with single vision:

“This life’s dim windows of the soul

Distorts the heavens from pole to pole

And leads you to believe a lie

When you see with, not through, the eye”

Blake’s promise, therefore, is that imagination frees you not to literally see more in the Sun, as if he were projecting joyous angels onto the fireball, but to see more with and through the Sun. He understands that it is not the physical eye that enables what we see, but the mind’s eye: the retina, optic nerve and brain are the servants, not masters, of perception. Blake tells us that the individual who perceives only the physical glow of the rising Sun in Ulro has opted to see that aspect of the Sun alone; the individual has sidestepped the part that imagination plays in what they perceive to arrive at an average star, in an average galaxy, lost in the vastness of the universe.

So, Generation is more expansive than Ulro. It gives Ulro’s reason a framework and purpose, though it continues to struggle with life’s higher dimensions. Moreover, the nagging sense that life should offer more therefore entails the risk of Generation pursuing its imaginative sprees unto seismic proportions: an escape into tedious reproduction. When this happens, society fills the landscape with the “dark Satanic mills” of the Industrial Revolution from Blake’s Jerusalem. Markets stock up on an endless variety of manufactured goods: vehicles, fashion, and processed foods. Infatuations come as they go. Consumerism reigns supreme.

Aware that scarcity follows abundance, people start to talk about survival of the fittest. The Ulro mentality manifests again, and people worry as replication blossoms like dew over a green leaf. As things run out of control, life is felt to be complexifying at exponential rates. But it’s not really. Life was always complex. Rather, people were disillusioned for lack of imagination. Just as before, the crisis becomes a stepping stone for entering the next petal of vision, Beulah.

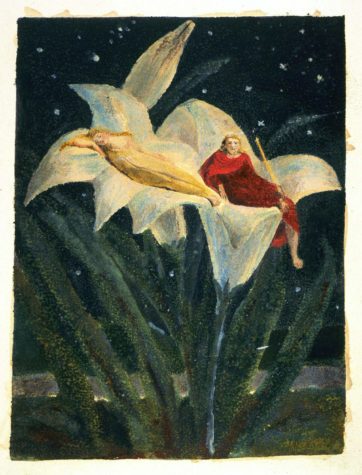

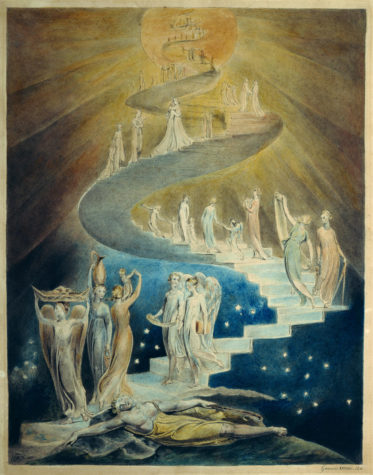

Beulah, the threefold vision, is the landscape of dreams. Here, all worries, responsibilities, and troubles vanish. It is a place of restoration and reflection, where rich seams of meaning and value, aspiration and recreation are uncovered. The contraries of life hold equally true, offering the narrower states of mind windows into new dimensions: Beulah can warm Ulro’s frosty reason and reorientate Generation’s haphazard reproduction. There is no life or death, they are both one and the same. Delighted with wonder, people in Beulah are prone to conversing with animals, holding séances with the dead, singing to the stars.

Beulah is acutely mindful of ethics and morality because it enjoys the minute particulars of life. Justice and fairness become significant principles for defending what it holds dear. However, Beulah has its dark side, too. It can be stifled by what Blake called ‘Selfhood,’ when love becomes possessive and wants to control relationships. In this mood, people cite rules over offering forgiveness, resort to the courts rather than mediate harmony, and when conflicts erupt on cultural grounds, ethics is weaponized in shaming, scapegoating, and propaganda. Selfhood ravages Beulah’s aspect of affection, leaving behind what Blake called ‘the Wastes of Moral Law.’ It divides, ostracizing people and fostering Ulro’s wariness by demanding that everyone embrace Beulah’s puritanical worldview. Flickers of hope are eclipsed by strings of hate.

It’s a perilous time. But if Beulah were to learn from its compulsions and stow away with Selfhood, it can discover greater horizons and an engagement with life freer than previously experienced. It is then that the final lifeworld can achieve takeoff in the fourfold vision, Eternity: the multifaceted perception that opens up a life of infinitude. Space becomes fractal, time fluid. It is a glimpse of forever, a sight so glorious and every moment so wonderful that every second of it makes life worth living. It happens as imagination is embraced as a living power of creativity with which we can cooperate. Eternity participates in nothing less than divine life, when imagination’s brilliance isn’t only spectacular and fun, but generative and lasting. Blake wrote in his celebrated poem Auguries of Innocence (1803):

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour”

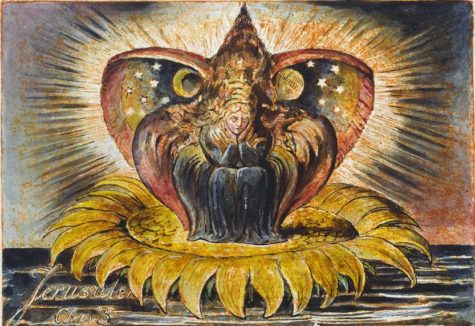

Eternity synthesizes the best aspects of each of its predecessors: the sophistication of Ulro, the splendor of Generation, the morality of Beulah. This makes it trustworthy for artists and visionaries alike. When Vincent van Gogh painted starry nights, the rippling cosmos became visible once again. When Carl Jung visualized the rebirth of God in The Red Book, he restored his inner being, and illuminated deep reaches of the unconscious mind. When Albert Einstein envisaged chasing a beam of light, which was the imaginative thought experiment that fostered the special theory of relativity, physics encountered new worlds. The ingenuities of science and the arts work hand-in-hand in Eternity, enriching each other. Blake celebrates such epiphanies in lines from Jerusalem:

“At the clangor of the Arrows of Intellect

The innumerable Chariots of the Almighty appeard in Heaven

And Bacon & Newton & Locke, & Milton & Shakespear & Chaucer”

Ethics ascend to higher aims, as well. It is no longer about Beulah’s defense of moral principles, but develops into what Blake called ‘Wars of Love,’ the effort to transcend old patterns of behavior and actualize the qualities of selfhood called virtues. To quote Blake’s Jerusalem, it happens by “laying / Open the hidden Heart in Wars of mutual Benevolence.” With such a cathartic act, Eternity judges to understand, not condemn; to liberate, not subdue. It welcomes mistakes as opportunities for spurring the kind of growth that transforms the soul and the mind.

The Wars of Love also transform the perception of death. In Ulro, death is impenetrable; in Generation, needless; in Beulah, a tragedy; but in Eternity, death is the gateway to fuller life. “Every kindness to another is a little Death,” wrote Blake, not just because each kindness might chip away at us, but because such sacrificial acts can be experienced by the giver as moments in which to realize that they never possessed life to start with. Rather, they live because life pours itself into us, like a waterfall gushing down on a pond. In Eternity, the everyday deaths through which we pass on life, as well as the seemingly ultimate death of passing over, reveal that there’s a source of life. It is a timeless love, a reuniting with the ocean, which includes and transcends death.

A changed meaning of freedom reveals itself now, although its claims might baffle or offend the states of mind that preceded Eternity. In Ulro, freedom is perceived to grow with an increased capability to grasp the world; in Generation, it’s equated with multiplicity of choice; in Beulah, with expression and dignity. But in Eternity, freedom is found in surrendering oneself to the impermanence of the world. This is because when yielding our present condition is perceived as the wellspring of life’s everlasting waters, it opens the door to embarking on new potential ventures. Blake sang of this bliss in his aptly-named quatrain Eternity:

“He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy

He who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity’s sunrise.”

Life is all about the flow. Enjoying things in the fleeting moments where they last is the best way to go about it. Only, once the sun sets on our endeavors, we will need to search for the fruits of joy once again, wherever they fly. That we have glimpses of beauty in nature makes us aware that the material world alone is too small for us. Eternity implies our capacity for transcendence means we are creatures of infinity. Blake tells us we can notice a “Heaven in a Wild Flower” and “Eternity in an hour” with a sense of reassurance that we will someday be able to awaken under Eternity’s sunrise, the imaginative beginning of wonder, like joy and beauty, that has no beginning and no end.

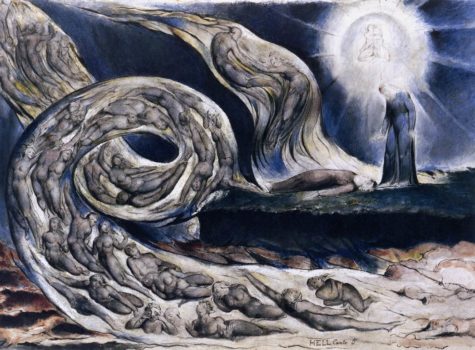

Ode to Wonder

In 1827, Blake would meet his fate while working on illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy. Though he was cheered by a small group of younger artists known as ‘The Ancients,’ he died largely unknown and penniless. While this portrays a tragic end to Blake’s story, it isn’t so. Blake died doing what he loved most, he died happy. Blake remained beside his wife of 45 years, singing hymns and verses to his very last breath. A fellow artist, George Richmond, wrote in a letter:

“He died… in a most glorious manner. He said he was going to that country he had all his life wished to see, and expressed himself happy, hoping for salvation through Jesus Christ. Just before he died his countenance became fair. His eyes brightened and he burst out singing of the things he saw in Heaven.”

Blake saw angels and dragons, ghosts and the heavens throughout his life on Earth. He held a true spirit of joy, an undying amazement at the wonders of the world. Wonder — that’s the crux of it. It is wonder that enabled Blake to see the world through, not with, the eye. It is wonder that urged him to consider imagination “the Body of God.” And it is wonder that cleansed Blake’s perceptions to connect him with his ultimate destination at the eternal realm. For us, learning from Blake’s example is not only important because it might counter the dangerous demands of the material world, but also because humans are made to enjoy the spiritual dimension. Renouncing Blake means renouncing a part of ourselves.

For most of us, at best, Eternity is glimpsed only on occasion. Such moments are signs, and they tempt us. In the long term, we cannot live in a well-functioning Beulah, nor can we mitigate the excesses of Generation’s escapism or Ulro’s rigidity, trapped in their own devices. But Blake’s life-story, the energy of his verse, his imagination, can help expand our vision in the light of the signs we receive, just as Blake experienced much awe having seen angels on Peckham Rye. The cosmos is alive and multiform. Pursuing its myriad pocket universes can become part of a lifetime. “Eternity is in love with the productions of time,” wrote Blake. That’s because Eternity is our destiny.

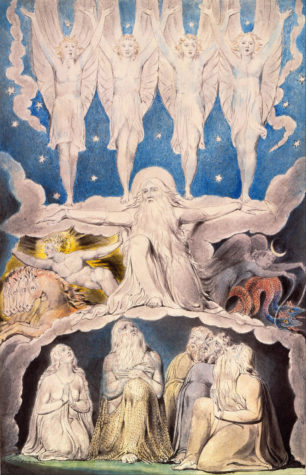

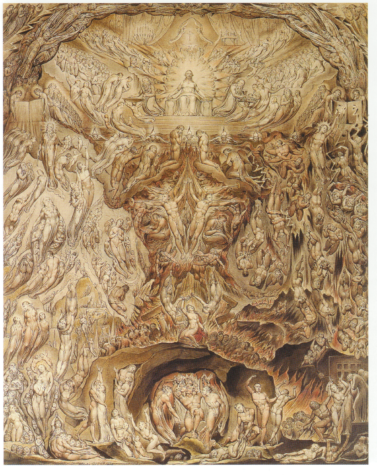

Fostering that aspiration feels crucial in our age. It’s become imperative to pay attention to the social atmosphere of minds in which we live, and move more fluidly between them. Blake’s fourfold vision offers a roadmap and guide. It’s a formidable task, as is any authentic shift of consciousness. But humans can cooperate with their potential for imagination and hope to someday awaken at the peak of their summit. And who knows — perhaps the journey will be well worth its hardships. To accompany his painting The Vision of the Last Judgement, Blake wrote:

“If the spectator could enter into these images in his imagination, approaching them on the fiery chariot of his contemplative thought… [If he] could make a friend and a companion of one of these images of wonder… then would he arise from his grave, then would he meet the Lord in the air, and then he would be happy.”

Blake’s philosophy of life can be summed up in one crucial insight: we don’t live in reality, we live in what we think reality is.

Rajin Tahsan is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ Rajin enjoys journalistic writing because it enables him to explore fascinating intersections...