‘Young Picasso in Paris’ at The Guggenheim: How ‘The City of Light’ Transformed the Artist

In 1901, a young Spanish artist arrived in Paris, unaware of the scale of transformation that he and his art would soon undergo. Currently, an exhibition at the Guggenheim museum asks us to evaluate this impactful and often overlooked period in Pablo Picasso’s life.

One of Picasso’s earliest French paintings, ‘Le Moulin de la Galette,’ is the collection’s crown jewel. It was recently restored in preparation for this exhibit.

When the name ‘Pablo Picasso’ comes up in conversation, you probably think of the fragmented figures, angular lines, or blue brushstrokes that compose the majority of his prized works of art. Yet, just as masterful, and often overlooked, are the paintings from his adolescence. These are snapshots that represent both the youthful promise and tangible loss that made up his early life.

Currently, a compilation of Picasso’s oldest artworks from his time in Paris are the subject of an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, entitled ‘Young Picasso in Paris,’ (open from May 12th – August 6th 2023) one of 30 Picasso exhibitions around the world commemorating the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death and his artistic evolution from starving painter to worldwide phenomenon.

Although he lived in France for the majority of his later years, Picasso was Spanish by birth. Born in the town of Malága, Spain, his artistic prowess emerged at a young age with the help of his father, Don Jose Ruiz, who was an artist in his own right and taught art oriented lectures at a local university.

Picasso’s family moved to Á Coruna in 1891, where Picasso’s creative talent continued to flourish. Here,Picasso truly came into himself, taking art classes at the college his father taught at and bumping up his creative output. But it is also where he experienced his first loss, as his beloved sister Conchita died in 1895 from diptheria, and the distress he felt following the tragic death is evident in his earlier works.

Soon after Conchita’s death, Picasso’s parents sent him away to Madrid Royal Academy, Spain’s premier art school, in order to cope and learn. However, due to a lack of interest in formal instruction Picasso soon dropped out, though he continued to absorb the rich artistic and cultural history present in the city.

This mindset of exploration and discovery led him straight to ‘the City of Lights,’ Paris, the go to destination for all artists and creative minds at the time. He arrived by train with his friend and fellow painter Carles Casagemas to visit the conclusion of the Universal Exhibition, where Picasso’s 1898 painting Last Moments was being featured.

What was Picasso’s mission? To enmesh himself in the artists, the models, and the paintings that made Paris such a cultural haven. He voraciously skipped from nightclub to dance hall to gallery, eagerly sampling everything that the city had to offer. He partook in the glamorous nightlife of the city, where he established himself within artistic and literary circles.

This period of discovery in his life is often overshadowed by the era of fame that was to come, where his bold, abstract figures pioneered a new and revolutionary style of art. Yet, it was during this time that Picasso became Picasso. He looked to the unconventional aspects of society, finding inspiration in the social gatherings of each class and the people who attended them. In Paris, and in these paintings, Picasso shed the skin of his academic training and forged his individualistic style against the backdrop of real life.

The Guggenheim museum channels his bold individualism throughout its exhibition, matching it with an air of refreshing simplicity. The ten painting collection is featured in just one room and follows his early Parisian journey.

The bare room echoes the clear cut lines and apparent simplicity of the museum exterior. The only color, aside from the paintings, is a rectangle of blue paint that stretches across all of the four walls and contrasts with the varying frames.

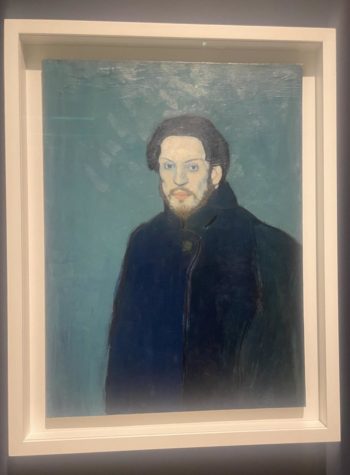

The first painting to meet the eye is a Picasso self portrait completed on cardboard, one of the four he would paint in 1901. This particular piece, simply called Yo, appears almost harsh to the eye. It is not meticulous, or carefully planned; on the contrary, quick lines of green and blue frame Picasso’s head, suggesting a rapid execution.

Yo, along with another 1901 portrait, also featured in the exhibition, Self Portrait, Paris, preface his career-defining “Blue Period,” that was to come. One can observe the stoic stares and halo of blue that reflects Picasso’s melancholia and mourning. Both are a reminder to the viewer that despite the colorful snapshots of high society that make up many of his earlier pieces, Picasso was increasingly using art as an outlet to his inward and darker thoughts.

Despite this, the use of bright pigment is a defining part of the exhibition. Picasso takes special attention to the female dress in particular, filling in broad hats and feathered gowns of yellow, blue and white. This is most apparent in The Diners (Les Soupeurs), where contrasting figures appear intently staring at a light spread and a bottle of champagne. The festive attire and friendly air of the woman is stark in comparison to the ponderous pose and formal clothing of the male figure. This piece is painted on cardboard, suggesting that Picasso drew this in a hurry due to financial constraints, and yet there is clear intent behind the oil. The figures reflect more than just a snapshot of urban nightlife; perhaps they are a reflection of societal standings or the isolation of urban life.

This idea of isolation is not quite as obvious in the crown jewel of the collection, Le Moulin de la Galette, a crowded picture featuring elegant couples in a late night dance hall. In an exhibit of only four walls, Le Moulin de la Galette alone occupies one of them, peering down at the viewer from a perch high above.

Although the composition is packed with people, it has a sort of solitude. This was one of the first paintings that Picasso painted in Paris, and yet he already grasped the quiet complexity of the crowd — its fashion, its gossip, and its gracefulness. After barely two months in the city, Picasso was irrevocably transformed in terms of his artistic style.

Le Moulin de la Galette was the source of a painstaking year and a half restoration undertaken by the Guggenheim museum in preparation for this exhibition. The painting was meticulously cleaned and relieved of 50 years worth of accumulated grime as well as a pesky yellow varnish that hadn’t coated the original picture. During the conservation, an insight into Picasso’s artistic process was also gained, including changes he had made to the piece as he worked.

One in particular comes in the form of a black lump in the lower left of the composition. Is it a lapdog? Picasso hastily obscured the animal with brown paint as he finished the painting, fearful it would eliminate attention from the figures, leaving only the outline and underlying color still slightly peeking through.

The alteration, although appearing seemingly unimportant, is the perfect representation of Picasso’s transformative forays in Paris. The artist constantly tweaked, altered and added to his own personal style as he delved deeper into the city’s crowded dance halls and packed restaurants. In Paris, in these ten pictures, Picasso came into himself.

In Paris, in these paintings, Picasso shed the skin of his academic training and forged his individualistic style against the backdrop of real life.

Allegra Lief is an Editor-in-Chief and an art critic for 'The Science Survey,' and is responsible for the review and revision of her peers’ articles...