Frank O’Hara’s Path to Poetic Stardom

Frank O’Hara championed an artistic movement centered around the city that never sleeps, transforming the mundane into objects of beauty.

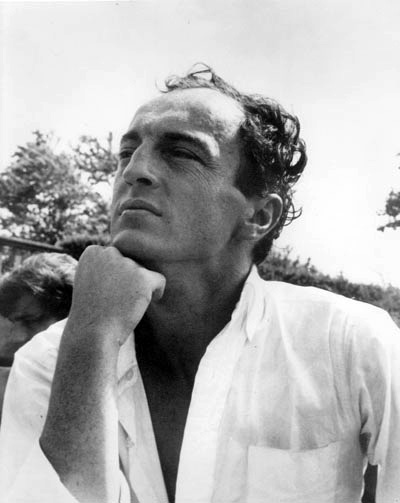

Kenward Elmslie, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Known as a social butterfly, avid intellectual, and superb artist, Frank O’Hara is pictured here in a moment of silent contemplation.

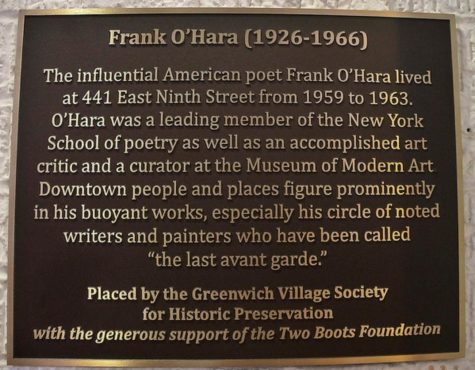

On July 25th, 1966, at the age of 40, Frank O’Hara, an innovative leader of the “New York School” of poets, died after being hit by a dune buggy on New York’s Fire Island.

Peter Schjledahl, an American art critic and poet who declared that O’Hara was one of his “heroes,” wrote a brief obituary in The Village Voice, noting that Larry Rivers “said he had always expected Frank to be the first of his friends to die, but “romantically,” somehow, voided by his generosities and done in by his methodical excesses, not shattered by a jeep on a white sand beach.” Schjledahl concluded, “At about 8:50 p.m., very suddenly, he was gone.” Thus, a life of poetic beauty came to a close in a moment.

Still, Frank O’Hara has lived on in New York City’s collective artistic conscience. Throughout his 15 years in the city (1951-1966), he wrote hundreds of poems in an almost messianic fervor, pouring his mind’s ferment into every rhyme and rhythm on the page, eager to capture everything from dance to art to ordinary discussions, all in a few eloquent stanzas. As Alex Katz, a renowned painter, said, “Frank’s business was being an active intellectual.”

Born in Maryland in 1926, O’Hara grew up in Massachusetts. Devoting his early years to studying piano, he fostered his artistic talents through classes at the prestigious New England Conservatory of Music. He wrote: “It was a very funny life. I lived in Grafton, took a ride on a bus into Worcester every day to high school, and on Saturdays took a bus and a train to Boston to study piano. On Sundays, I stayed in my room and listened to the Sunday symphony programs.”

During World War II, O’Hara served in the U.S. Navy for two years on the destroyer USS Nicholas, and he was stationed in both Japan and the South Pacific. Following his brief military stint, he enrolled at Harvard, where he forsook his love of music in order to pursue English. It was in majestic libraries and his shared dorm room – a prime spot to “lie down on a chaise longue, get mellow with a few drinks, and listen to Marlene Dietrich records” – that O’Hara was inspired by the ingenious works of Boris Pasternak, Arthur Rimbaud, and Vladimir Mayakovsky.

At Harvard, O’Hara also met John Ashbery, one of the greatest of 20th-century American poets, who also earned a distinguished place in O’Hara’s inner circle of artistic visionaries. Soon, O’Hara began publishing poems in The Harvard Advocate and ventured between Boston and New York City, connecting with poets such as Kenneth Koch and painters including William de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, Jane Freilicher, and the famed Abstract Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock.

While his budding collection of poems bore the potential to earn him a place with history’s literary giants, O’Hara’s fame rested with his passionate personality. He was a witty wordsmith, captivatingly clever and creative, a humorous individualist, and a pugnacious proponent of his patchwork opinions on pop culture (Frank Sinatra: brilliant talent, Looney Tunes: a work of genius, Rita Hayworth: absolute Venus!). He liberally shared his occasionally controversial opinions, frequently picked fights over music, and sought to learn from the greatest artistic minds in the game.

After graduating from Harvard, O’Hara attended graduate school at the University of Michigan, where he earned his M.A. in 1951 in English Literature. After moving to New York City, he published his first volume of poetry, A City Winter, and Other Poems (accompanied by drawings by Larry Rivers) and wrote brilliant essays about sculptures and paintings for Art News.

Simultaneously, he dabbled with artists; John Ashbery noted that Kenneth Koch once said to him, “I wonder what it would be like to know O’Hara.” Thus, O’Hara made his grand entrance into the art world, spending joyful times dining with trailblazing poets and painters at the Club and the Cedar Tavern. As he listened to artists argue and gossip, he wrote a plethora of poems, stuffing them in his pockets and later haphazardly in random drawers.

He also earned a job as a clerk in the front lobby of the Museum of Modern Art during the Christmas rush of the Matisse show. In five years, he became an assistant curator and eventually an associate curator of painting and sculpture. He assisted in curating 19 diverse exhibitions including “The New American Painting,” which moved between eight European cities from 1958 to 1959.

Ashbery wrote that American painting “absorbed Frank to such a degree, both as a critic for Art News and a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, and as a friend to the protagonists, that it could be said to have taken over his life.”

In 2019, the MoMA dedicated an entire room – ‘Frank O’Hara, Lunchtime Poet’ – to their famous curator. A double portrait of O’Hara by Larry Rivers along with a passage from the poem ‘Steps,’ welcomec visitors: “oh god it’s wonderful / to get out of bed / and drink too much coffee / and smoke too many cigarettes / and love you so much.’ For Rivers, O’Hara was an elusive subject; “I always felt I was close to getting him but I never did, so I kept on trying,” Rivers said. Countless other artists from Elaine de Kooning to Alex Katz similarly tried to capture O’Hara in their sweeping paints.

In 1965, O’Hara ascended to partial fame with the publication of his eloquent collection Lunch Poems. His meteoric debut of a light, highly humorous panoply of poems reflects the casual nature in which he composed his pieces. He wrote his poem “Poem (Lara Turner has collapsed!)” on the Staten Island ferry and completed his manifesto “Personism” within less than an hour.

“When asked by a publisher-friend for a book, Frank might have trouble even finding the poems stuffed into kitchen drawers or packed in boxes that had not been unpacked since his last move. Frank’s fame came to him un-looked for,” said John Button, a painter known for his marvelous cityscapes.

Still, it was O’Hara’s scatterbrained creativity and impulsive urges to type away which lay at the very heart of his genius. “Something Frank had that none of the other artists and writers I know had to the same degree was a way of feeling and acting as though being an artist were the most natural thing in the world. Compared to him everyone else seemed a little self-conscious, abashed, or megalomaniacal,” Koch said.

Throughout the remainder of his tragically short life, O’Hara published over a hundred poems in various publications but only produced two volumes Lunch Poems and Second Avenue. Posthumously, Collected Poems (1971) and The Selected Poems of Frank O’Hara (1974) were published, earning O’Hara the recognition he had not sufficiently reaped throughout his career.

O’Hara’s literary style is distinctive in its detail, colloquial quality, and its blend of surrealist and postmodern techniques and devices. Endlessly witty as he divulges his feelings with the subtlety of a poorly kept secret and crafts elegies for friends, celebrities (for example, Billie Holiday and Jackson Pollock), his shifting surroundings, and even himself, O’Hara attempts to immortalize the moment. In “A Terrestrial Cuckoo,” he writes, “What a hot day it is! for / Jane and me above the scorch / of sun on jungle waters to be / paddling up and down the Essequibo / in our canoe of war-surplus gondola parts.”

Forever centered around New York, Frank O’Hara paints vivid images of city life. In one poem he writes “It’s my lunch hour, so I go / for a walk among the hum-colored / cabs. First, down the sidewalk / where laborers feed their dirty / glistening torsos sandwiches / and Coca-Cola, with yellow helmets / on.” It is these laconic elegies which are designed to freeze time and embody the vibrant buzz of city life. In another poem ‘At the Old Place,’ he writes about Penn Station, “Down the dark stairs drifts the steaming cha- / cha-cha. Through the urine and smoke / we charge / to the floor. Wrapped in Ashes’ arms I glide.”

Then, at 40, a dune buggy on a beach on Fire Island ended O’Hara’s career and his life, through a tragic accident. He died of a ruptured liver, leaving behind the poems he had stuffed in his pockets, in empty drawers, and in between pages of beloved books.

As Alex Katz, a renowned painter, said, “Frank’s business was being an active intellectual.”

Katia Anastas is an Editor in Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She loves that journalistic writing equally emphasizes creativity and truth, while allowing...