Joan Didion’s Luminescent Literary Legacy

At 87, Joan Didion passed away due to complications associated with Parkinson’s disease. A chronicler of subtle cultural shifts, the vicissitudes of American politics, and her own emotional journeys, Didion leaves behind a rich trove of treasured writing.

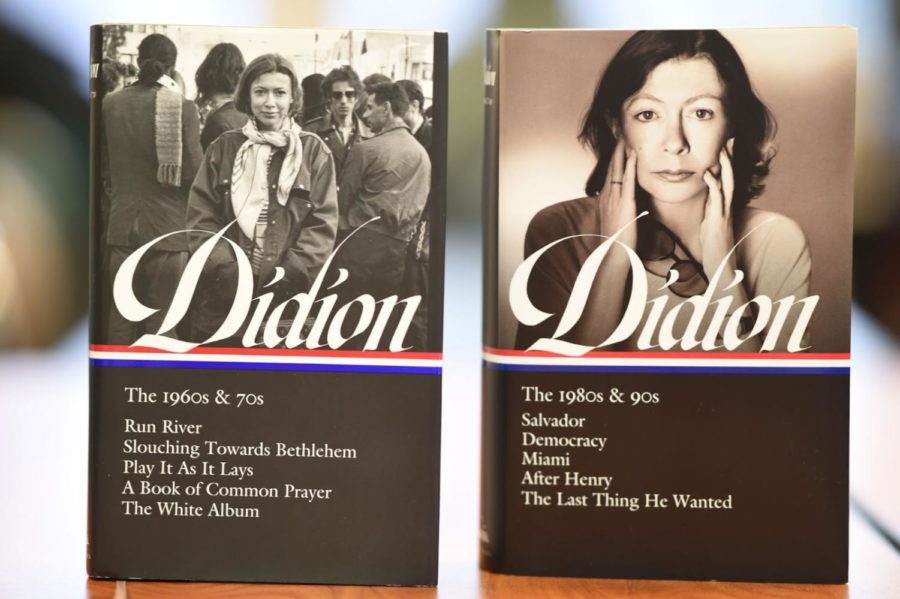

The Library of America has published Joan Didion’s seminal works from the 1960s through 1990s in two separate volumes.

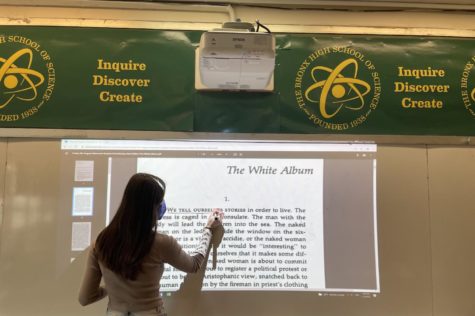

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan Didion wrote in The White Album. Her own stories – sharp accounts of the dark undercurrents of the 60s and 70s, the golden rhythm of the city that never sleeps, the heartless voids of grief and tragedy, and the political and social tumult of the United States – breathed life into a generation by affording readers the gift of her elegant narrative line.

On December 23rd, 2021, Didion passed away alone in her home in Manhattan due to complications associated with Parkinson’s disease. She outlived both her husband, John Gregory Dunne, and her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne. She was 87. Now, Didion’s luminescent literary legacy remains.

Didion wrote in ‘On Keeping a Notebook’ that she began writing when her mother gave her a notebook “with the sensible suggestion that I stop whining and learn to amuse myself by writing down my thoughts.” As a teenager, she typed up chapters from Ernest Hemingway’s novels in order to examine how they worked. “There was just something magnetic to me in the arrangement of those sentences. Because they were so simple — or rather they appeared to be so simple, but they weren’t,” Didion said.

While completing a bachelor’s degree in English during her junior year at the University of California, Berkeley, Didion submitted a short story to Mademoiselle and won a spot as guest fiction editor for the magazine. Still, in a 2006 interview, she explained that writing “began to feel almost impossible at Berkeley because we were constantly being impressed with the fact that everybody else had done it already and better. It was very daunting to me.”

The next year she won an essay contest spearheaded by Vogue. Instead of claiming an extravagant trip to Paris, Didion began working at the elite magazine. Far from a The Devil Wears Prada experience, Didion developed a distinctive prose at Vogue as an associate features editor. “In an eight-line caption everything had to work, every word, every comma,” she remarked.

Didion carried the same laser beam precision to her later works. After writing feature articles in Life Magazine and The Saturday Evening Post that examined the political and social hemorrhaging of postwar American life and publishing her first novel Run, River about the unraveling of a Sacramento family, she published two trailblazing essay collections: Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) and The White Album (1979).

These two collections captured, in precipitously eloquent prose, the mood of the cultures of the 1960s and 70s in California. For Didion, these two decades were rife with chaos and uncertainty. Didion, who observed that she herself fell into a category of “lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss,” found her muse in the dark trouble spots of these tumultuous times, from the Manson murders to the hippie community of Haight-Ashbury. Didion noted in an interview, “I can recall disapproving of the golden mean, always thinking there was more to be learned from the dark journey.” Thus, Didion felt an almost magnetic pull to social and political fragmentation.

Didion attributed her attraction to danger to her early years in Sacramento, a city of extremes. “The weather in Sacramento was as extreme as the landscape. There were two rivers, and these rivers would flood in the winter and run dry in the summer. Winter was cold rain and tulle fog. Summer was 100 degrees, 105 degrees, 110 degrees. Those extremes affect the way you deal with the world. It so happens that if you’re a writer the extremes show up. They don’t if you sell insurance.”

In her essay, ‘Notes from a Native Daughter’ Didion chronicled the sun bathed, dilapidated towns of California, examined the fading diamond iridescence of the aristocratic scene, and delved into her memories of the silt rich rivers that were also a danger to playful children. Burdened by the deadweight of Californian tragedies and microscopic societal shifts, Didion broke through icy frozen ground to become a literary rose, noting that in California “the mind is troubled by some buried but ineradicable suspicion that things had better work here, because here, beneath that immense bleached sky, is where we run out of continent.”

In these groundbreaking essay collections, Didion examined, under a crystalline lens, the golden opportunity and fading glory, the dreamy visions and anarchic beauty, and the cultural magnetism and violent fervor of her home state. In The White Album, Didion eerily wrote: “I imagined that my own life was simple and sweet, and sometimes it was, but there were odd things going around town. There were rumors. There were stories. Everything was unmentionable but nothing was unimaginable. This mystical flirtation with the idea of ‘sin’ – this sense that it was possible to go “too far.” and that many people were doing it – was very much with us in Los Angeles in 1968 and 1969.”

Didion was magically attuned to the mysteries of California. Her writing style – candid and incantatory, hauntingly precise and dazzlingly detailed, full of resplendent rhythms and laconic literary lore – enabled her to capture, through a sequence of anecdotes and meditative reflections, chilling subject matter, ranging from her own grief to the random violence which plagued her home state during the 70s. Never omitting the “implacable ‘I’” from her narratives, she became a member of the school of New Journalism, which fused elements of fiction and nonfiction.

The candor of her writing style is glaringly evident in her essays. Didion acknowledges her own subjectivity, pinpoints her confusion, identifies her blind spots, and questions — with a cold twinkle of critical perception — the reliability and truth value of her own stories. Didion wrote, “I wanted still to believe in the narrative and the narrative’s intelligibility, but to know that one could change the sense with every cut was to begin to perceive the experience as rather more electrical than ethical.” Importantly, Didion developed a strong appeal to ethos with readers by cataloging her own doubts. She transformed herself from a distant chronicler to a living, breathing writer capable of faults and fantasy.

“I tell you this not as an aimless revelation but because I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind,” Didion confessed in The White Album, discarding the classic principle of journalistic self-effacement for a more avant-garde, personal style.

Importantly, by harnessing the power of the ‘I,’ Didion ventured through the labyrinthine paths of thought, diving beneath the rational surface to psychic, mystical depths. At face value, she found ideas to be “dense with superstitions and little sophistries, wish fulfillment, self-loathing and bitter fancies.” Thus, not seeking approval or praise, Didion went straight to the heart of societal ills and personal delusions and commanded authority through her captivating prose. As Zadie Smith writes in The New Yorker, Didion “could speak without hedging her bets, without hemming and hawing, without making nice, without poeticisms, without sounding pleasant or sweet, without deference, and even without doubt.”

While Didion charmed the masses, she also acquired certain critics. In her New York Times article ‘The Cult of Saint Joan,‘ Daphne Merkin questions Didion’s candor as she writes, “Didion’s voice exudes a uniquely distanced sort of intimacy, messaging “come close” in one sentence and then “stay away” in the next.”

Although absolute honesty can neither be discerned nor proven, Didion repeatedly placed her raw emotions and naked thoughts in the limelight. In her essay, ‘In the Islands,’ Didion confessed to being on the verge of divorce, and in The White Album, she portrayed herself as an incredibly neurotic, frail woman prone to the pangs of fear and disenchantment. The minority of Didion’s sentences which Merkin’s alleges exude secrecy only reinforce aspects of Didion’s own character in terms of her biting cynicism and pervasive peculiarities. Moreover, these sentences subtly remind readers that it is virtually impossible to comprehend another person entirely. In Blue Nights Didion writes that often “our investments in each other remain too freighted ever to see the other clear.”

Still, Didion observed in an interview, “I wrote stories from the time I was a little girl, but I didn’t want to be a writer. I wanted to be an actress. I didn’t realize then that it’s the same impulse. It’s make-believe. It’s performance.” Didion was incredibly conscious of the imposition of her own worldview on the page, a raging reality to her and a figment of fiction to others. She said that writing is a hostile act “in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it, trying to impose your idea, your picture. It’s hostile to try to wrench around someone else’s mind that way.”

Acknowledging that Didion was the “archpriestess of the cool,” Merkin levies another criticism against Didion: elitism. Even while chronicling the paroxysms of grief, Merkin notes that Didion includes details that hint at wealth and extravagance: the name of a store in Beverly Hills where she bought a robe, the chic restaurants she and her husband used to dine at, and her position as chairman of her co-op board.

Importantly, Merkin ignores Didion’s desire to generate an atmospheric narrative line by artistically embroidering details into her works. Didion put forth the world as she knew it; she was just as eager to outline the particulars of luxury or loss, mirth or melancholy. While there is an image of Didion, haloed by literary reverence and surrounded by the golden fruits of her labors, that is somehow inscribed in her dark sunglasses and implied by her flashy Park Avenue address, she was neither defined nor detoured by any of the external circumstances of her life; instead, she chronicled what she knew and sought truth through her masterful prose.

Lastly, Merkin accuses Didion of being too removed from her narratives. Fueling an aura of disenchantment and distance, Didion’s world was permeated by a sense of playacting, the flawed idea that society’s discordant discontents and explosive ironies and violent fissures emerged only to be printed on the page, the suspicion that someone might just call ‘cut’ and the colors would fade and the credits would roll.

While in California, Didion and her husband also tackled screenwriting as a formidable, openly cynical team. The ambitious pair left Manhattan on the heels of a get-rich scheme motivated by the golden promise of Hollywood. Without having ever written or read a single script, Didion and Dunne offered their Midas’ literary touch to the often arbitrary movie business. “This place makes everyone a gambler,” Didion observed of Hollywood.

Unfortunately, the duo’s roll of the dice did not fill their pockets with a steady stream of cash. In 25 years, Didion and Dunne were credited on the big screen solely six times for movies such as ‘Play It as It Lays’ and ‘True Confessions.’ While screenwriting was meant to grant Didion the ability to pursue serious art, a great deal of her time was wasted on unpaid draft revisions.

Thus, Didion and Dunne adopted a cynical outlook on Hollywood’s flashy allure; Didion mocked the film industry in essays and Dunne published The Studio, a nonfiction book which outlined how a 20th Century Fox publicist sold Doctor Dolittle so convincingly that it received nine Oscar nominations despite mixed reviews. Ironically, as the couple wrote about the inconsistencies and oddities of the movie business, their script fees rose dramatically. Cynicism cast a flattering light upon the pair who were viewed as savvy and smart. As Dunne joked, “I have never been quite clear what Going Hollywood meant exactly, except that as a unique selling proposition, it’s a lot sexier than Going University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop.”

Beyond the big screen, Didion pursued political reporting. She published extensive essays for The New York Review of Books on the civil war in El Salvador and the Cuban émigré culture of Miami. In an interview, she said “I thought it was really interesting that so much of the news in America… was coming out of our political relations with the Caribbean and Central and South America. So when we got the little apartment in New York, I thought, well that’s something useful I can do out of New York: I can fly to Miami.”

She also turned her eye to the pandemonium of American politics, undressing ugly truths and analyzing the vicissitudes of current events. Didion accurately identified the corporate restraints, ideological inconsistencies, and self-serving nature of politicians who render our democratic system paralyzed and powerless. “Something about a situation will bother me, so I will write a piece to find out what it is that bothers me,” she said.

Importantly, Didion’s journalistic writing possesses a prophetic flair. She was incredibly prescient in writing about political polarization and the erosion of truth within the framework of American democracy. Decades ago, she wrote of the deleterious influence of political and media elites who “invent, year in and year out, the narrative of public life,” fueling partisan divides and fanning the flames of prejudice. Moreover, in 2003, she wrote that our political process relies on the ability of individuals to turn “the angers and fears and energy of the few” against “the rest of the country.” Now, it is becoming increasingly clear that we are all living in an America that is eerily similar to Didion’s.

Later in her life, Didion experienced two profound tragedies: the death of her beloved husband, John Gregory Dunne, and the death of her adopted daughter, Quitana Roo Dunne. Mr. Dunne died of a heart attack at 71 in 2003; Quitana Roo died of pancreatitis and septic shock two years later at 39.

While death, destruction, and apocalyptic anarchy had long been subjects of Didion’s writing, they soon turned from themes to realities. In an interview in 1978, she said, “The death of children worries me all the time. It’s on my mind. Even I know that, and I usually don’t know what’s on my mind.”

Using tragedy as her muse, Didion wrote about her husband’s death and daughter’s medical conditions in The Year of Magical Thinking which won the 2005 National Book Award for nonfiction, and wrote about her daughter’s death in Blue Nights. Didion reflected that what happened to her family “cut loose any fixed idea I had ever had about death, about illness, about probability and luck, about good fortune and bad, about marriage and children and memory, about grief.”

Didion elegantly weaved memories and scenes from the present into both of these works. In Blue Nights, she recalled adopting a beautiful baby with dilated eyes and soft skin, her family trips to Hawaii and the sparkling beaches of Malibu, the details of Quitana’s wedding day – her creamy white dress, beautiful blond braid, and the bright-red soles of her shoes. These images, laced with brightness, the assumption that happiness and health were breezy blessings, and a naivete that can only be discerned through the harsh lens of the future, are juxtaposed by the shock of her daughter’s death and the impermanence of life itself. Similarly, The Year of Magical Thinking juxtaposes the horror of death with the beauty of marriage through shadowy, poignant prose.

Unstrung by a deep abyss of melancholy, Didion wrote in The Year of Magical Thinking, “Nor can we know ahead of the fact (and here lies the heart of the difference between grief as we imagine it and grief as it is) the unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaninglessness itself.” Clear and precise, Didion transformed a story that began with a heart attack on the Upper East Side into a powerful, universal tale of grief.

Her candor and charm fashioned her into an impactful narrator. Didion frequently posed questions to herself throughout these two books surrounding the intimacy of her marriage, her role as a mother, the swift passage of time, and the importance of memory which seals moments in cool wax. While Didion observed that “I developed a sense that meaning itself was resident in the rhythms of words and sentences and paragraphs, a technique for withholding whatever it was I thought or believed behind an increasingly impenetrable polish”, in The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, Didion scraped away the polish and put forth her unadulterated thoughts.

Didion’s most memorable works trace the arc of life and outline the inevitability of death. Her best pieces uncover “the ways in which people do and do not deal with the fact that life ends.” Importantly, the deaths of her husband and daughter reinforced what Didion already knew – that she was mortal as well, that death is an inescapable constant we all ignore until it comes knocking on our door. “We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all,” Didion wrote in The Year of Magical Thinking.

Plagued by a presentiment of loss, Didion observed even in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, that “We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.” The cruel hand of time was forever on Didion’s mind.

In an attempt to preserve the moment, to develop snapshots of the time, to chronicle the quicksilver changes and shifting sands of thought, Didion lived her life entirely “by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images.” She found meaning resident in words and solace in sentences which teased through her complicated web of thoughts concerning love, motherhood, life, and death.

Now, she will enjoy the immortality which her writing has afforded her. Trailblazing and unique, resilient and strong, inspiring and alluring, Didion will claim her place in history as one of the greatest American writers of all time.

“We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all,” Joan Didion wrote in The Year of Magical Thinking.

Katia Anastas is an Editor in Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She loves that journalistic writing equally emphasizes creativity and truth, while allowing...