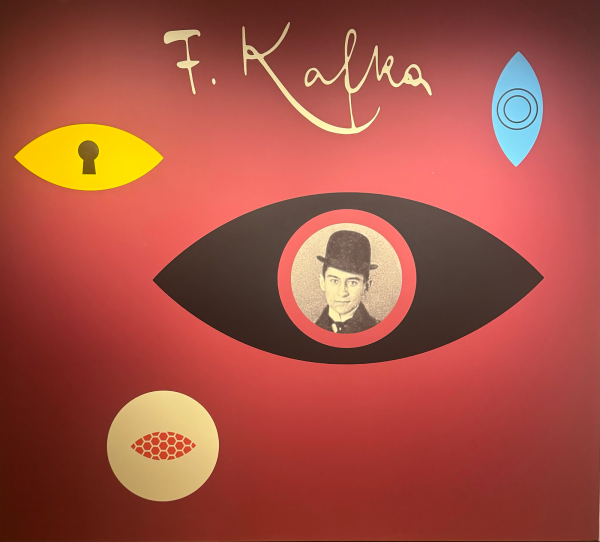

Trapped in the body of a bug and no longer recognized as human by the people he cared about, Gregor Samsa in The Metamorphosis was already stuck even before his transformation. He had a monotonous job he felt no passion for, but he continued to work hard to provide for his family— the same family that had been using him for financial support and would eventually refuse to even look at him in his fragile state. The story of Gregor Samsa is a surreal and gloomy tragedy, and while many readers draw parallels between Gregor and Franz Kafka, the author of The Metamorphosis, the reality is far more complex. The Franz Kafka exhibit at The Morgan Library & Museum, currently on view through April 13th, 2025, offers a glimpse into the mysteries of Kafka’s life, educating visitors about the kind of man he truly was, in order to challenge the common misconceptions about him.

Towards the entrance of the gallery is a large picture of Kafka’s face, which was crafted by the artist Andy Warhol. The vibrant recreation of an original picture of Kafka with his fiancée, Felice Bauer, centers only on Kafka’s face. The print was created in 1980 and featured in Warhol’s Jewish portfolio which he made in order to commemorate significant Jewish figures. In this profile, Warhol steers away from his usual subject of pop icons and focuses directly on Jewish people involved in arts, literature, and science. The print is extremely striking, with the use of vibrant blue-green colors and the accent of a muted red outlining Kafka’s stern expression. The use of shadows and sharp lines accentuate Kafka’s features to highlight his Jewish identity and shed light on the complexities of his literature and life.

Kafka’s Jewish identity is heavily explored throughout the exhibit. Although Kafka and his family participated in many Jewish traditions, they did not consider themselves to be extremely religious. Kafka had a fond appreciation for Jewish art and theater and could often be found at a Yiddish theater. Kafka knew a small amount of Hebrew as a boy, but he made an effort to teach himself more as he got older. On display at the exhibit is a book of German words that Kafka translated into Hebrew while he was learning the language. In Eastern Europe at the time, Yiddish was the traditional language of most Jews and was spoken by anti-Zionists, while Hebrew became the leading language of the Zionist movement. Kafka was motivated to learn Hebrew because he was a Zionist and wished to eventually settle in Israel.

Although a common theme in many of Kafka’s writings is solitude and alienation, a common misconception about Kafka was that he was lonely and estranged. The exhibit showcases postcards from family and friends to show the deep relationships that Kafka had during his lifetime. Kafka dealt with many physical and mental issues; however, he was still affectionate toward his loved ones and those around him. Images of Kafka are widespread but often altered in a way to make him appear more lonely than he was. When one searches for images of Kafka on the internet, many of the images show him in a dark, isolated setting. Many of these images are edited or cropped to depict Kafka as a lonely, misunderstood artist to align with his public image and writings.

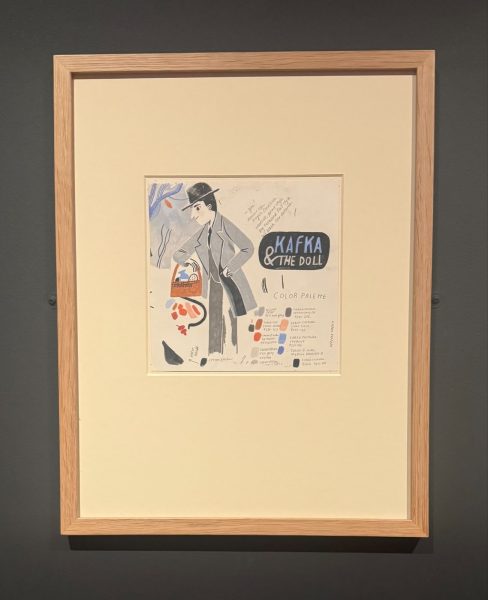

Dora Diamant, Kafka’s last love, told a story about how Kafka met a little girl in a park who lost her doll. To a little girl, the loss of a doll is a dreadful calamity that can cause great heartbreak. Kafka empathized with the girl and claimed that her doll was not lost, but that instead instead she was traveling around the world. To support this claim, Kafka wrote letters pretending to be her doll to convince the girl of this story. This presents viewers with a tender, caring side of Kafka that is often masked by his gloomy, misunderstood portrayals. Although the letters Kafka wrote were lost, they inspired a plot to a children’s book called Kafka and the Doll written by Larissa Theule and illustrated by Rebeca Green.

Traveling was an activity that Kafka participated in frequently. Lined across the exhibit are postcards that Kafka sent to his family members throughout his travels. His postcards introduce a more playful side to him, where he often includes jokes, anecdotes, and little doodles. The postcards and letters further explore Kafka’s personal life and family connections. Kafka traveled across Europe with Max Brod, a writer and journalist and one of Kafka’s closest friends, before World War I began, and he would send a postcard back home every time. Kafka’s most enthusiastic postcards were the ones sent to his little sister Ottla, with whom he was very close.

While traveling, Kafka kept travel diaries, which are displayed in the exhibit, in order to record his thoughts; they were used as inspiration for his writings. Kafka’s manuscripts also went on multiple travels as the benefactor of his work was forced to evacuate Europe during World War II. After Kafka’s death due to tuberculosis, he left his cherished writings with his friend Max Brod. He instructed Brod to burn all of his work; luckily, Brod refused and disregarded Kafka’s wishes. Kafka often doubted his talents and burned a lot of his work because he felt it was not good enough. It is speculated, however, that Kafka knew that Brod was too supportive of a friend to burn his work and accepted that he would simply disregard his wishes.

The exhibit maps the extensive journey that all of Kafka’s writing took as they traveled throughout Europe and the Middle East. During World War II, Brod was able to escape Europe and travel to Palestine with Kafka’s manuscripts on the last train that departed before the borders were closed. As he settled in Tel Aviv, Brod began to edit all of Kafka’s work and eventually handed it over to Salman Schocken. Salman Schocken was a Jewish publisher known for publishing the works of writers who were rejected by German publishers. Kafka’s writings were banned in Germany and Czechoslovakia by the Nazis. Fortunately, in 1989, Czechoslovakia lifted its ban on Kafka’s work, allowing his work to return back to his homeland.

Unfortunately, Kafka’s sisters were not able to escape the harsh conditions of the Holocaust and tragically died in concentration camps. However, their daughters survived and later took ownership of Kafka’s manuscripts. During the Suez Crisis, Schocken moved the manuscripts to Zurich Bank, and later Kafka’s nieces loaned them to the Bodleian Library in Oxford, where most of his writings remain today.

One of Kafka’s most famous and final novels is The Castle, which is considered a canonical classic work of literature to this day. The Castle remains an unfinished work and was originally untitled, as Kafka died before he was able to complete his story. Brod added the title to the story and was able to edit and publish the story along with Kafka’s other works, like The Trial and Amerika: the Missing Person. Although The Castle has an abrupt ending, it allows readers to speculate and guess the intended end of the novel, aligning with the constant mystery of Kafka himself. This exhibit and all of his writings offer insight into his life, but there will always be unexplainable aspects to Kafka’s life and work.

Some of Kafka’s favorite works of literature and art have Asian origins. One of Kafka’s favorite books was Hans Heilmann’s 1905 German translation of a selection of Chinese poems. Kafka owned many German-translated books related to Taoism and found great interest in Chinese philosophy. Fast forward a century, and the tables have turned; Kafka’s work is now the subject of translation for Asian audiences. South Korean writer Bae Suah has dedicated herself to translating some of Kafka’s works into Korean, making them accessible to a more diverse audience. She also uses some of Kafka’s quotes in her novella, Milena, Milena, Ecstatic. Kafka was also deeply influenced by Japanese art styles, and Asian artists and writers now use Kafka as inspiration. The book Kafka on the Shore, written by Haruki Murakami, is greatly influenced by Kafka and his style of writing.

Kafka was exceedingly open-minded about a multitude of cultures and demonstrated a deep intellectual curiosity toward them. Although Kafka never received the chance to venture outside of Europe to places like Asia and Africa, he often used his imagination to create stories from the perspective of a European voyager arriving and exploring different continents.

Few writers have had as immense an impact as Kafka, whose name has become an adjective describing real-world experiences. The word Kafkaesque is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “Of, relating to, or characteristic of the writings of Franz Kafka; resembling or reminiscent of the state of affairs or a state of mind described by Kafka; esp. characterized by nightmarish or perplexing circumstances, or subjection to a complex, oppressive, and seemingly illogical bureaucracy.” The word is a way to characterize disorienting situations similar to the ones Kafka created in many of his works of fiction. Throughout Kafka’s life, he experienced many Kafkaesque moments. The most notable and ironic moment is how Brod chose to publish Kafka’s work without his permission after his death. This made Kafka powerless over the decisions made about his own work, which relates to how the word Kafkaesque represents people who are trapped in forces beyond their control.

The ‘Franz Kafka’ exhibit at The Morgan Library & Museum offers a nuanced representation of Kafka. Through the use of vibrant artwork, portraits, personal mail and journals, the exhibit highlights Kafka’s identity and empathetic nature. His legacy continues to inspire readers worldwide. Despite the mysteries surrounding his life, Kafka’s literary influence remains undeniable. Kafka’s writings parallel the journey of his manuscripts across continents, as both reflect themes of displacement, survival and uncertainty. His manuscripts withstood censorship, war and legal battles before finding their home in libraries and museums around the world. Despite the risk of being lost — both in fiction and reality — Kafka’s voice has endured, shaping literature across generations.

The ‘Franz Kafka’ exhibit at The Morgan Library & Museum offers a nuanced representation of Kafka. Through the use of vibrant artwork, portraits, personal mail and journals, the exhibit highlights Kafka’s identity and empathetic nature. His legacy continues to inspire readers worldwide.