“Look out, kid, don’t matter what you did

Walk on your tip toes, don’t tie no bows

Better stay away from those that carry around a fire hose

Keep a clean nose, watch the plainclothes

You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows”

From Bob Dylan’s lyrics, “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows,” in the song Subterranean Homesick Blues, a revolutionary organization in the United States acquired its name.

In May 1970, Weather Underground leader Bernardine Dorhn made public a declaration of war against the United States. Throughout the next ten years, the organization dedicated themselves to fighting American imperialism and white supremacy.

To the Weathermen, soon renamed the Weather Underground, the momentum of action was “blowing with the wind.” The fugitive organization strove to persuade people to abandon their deference to authority, a deference that was complicit in the evils of imperialism and wars of mass destruction. Instead of adhering to the privileged in power, people needed to give power to the disenfranchised and “become their own weatherman.”

By the 1980s – after the Vietnam War was won by the North Vietnamese – the Weather Underground had essentially disbanded. Members began to resurface back into normal life, starting families and resuming their public activism.

Origins of The Weather Underground

During the 1960s, youth liberation movements were in full momentum, protesting sexism, racism, homophobia, and imperialism. However, by 1968, many grew disillusioned with the lack of progress that appealing to the United States government through mass non-violent protests engendered. In Vietnam, daily news of bombings, massacres, and casualties in the thousands – all under a liberal President – facilitated a shift from peaceful protest to militancy. The continuation of systemic racism despite the Civil Rights Act of 1968 also led to a surge of Black Power movements. Groups such as the Black Panther Party championed community uplift and protection from police brutality rather than participation in rigid and traditional politics.

In this tumultuous atmosphere, a militant faction of the Students for a Democratic Society formed an underground organization dedicated to “bringing the war home.” Instead of a broad antiwar movement, the Weather Underground saw themselves as revolutionaries. In support of the National Liberation Front (NFL), they declared war on the United States in an official communique.

“Extreme Vandalism”

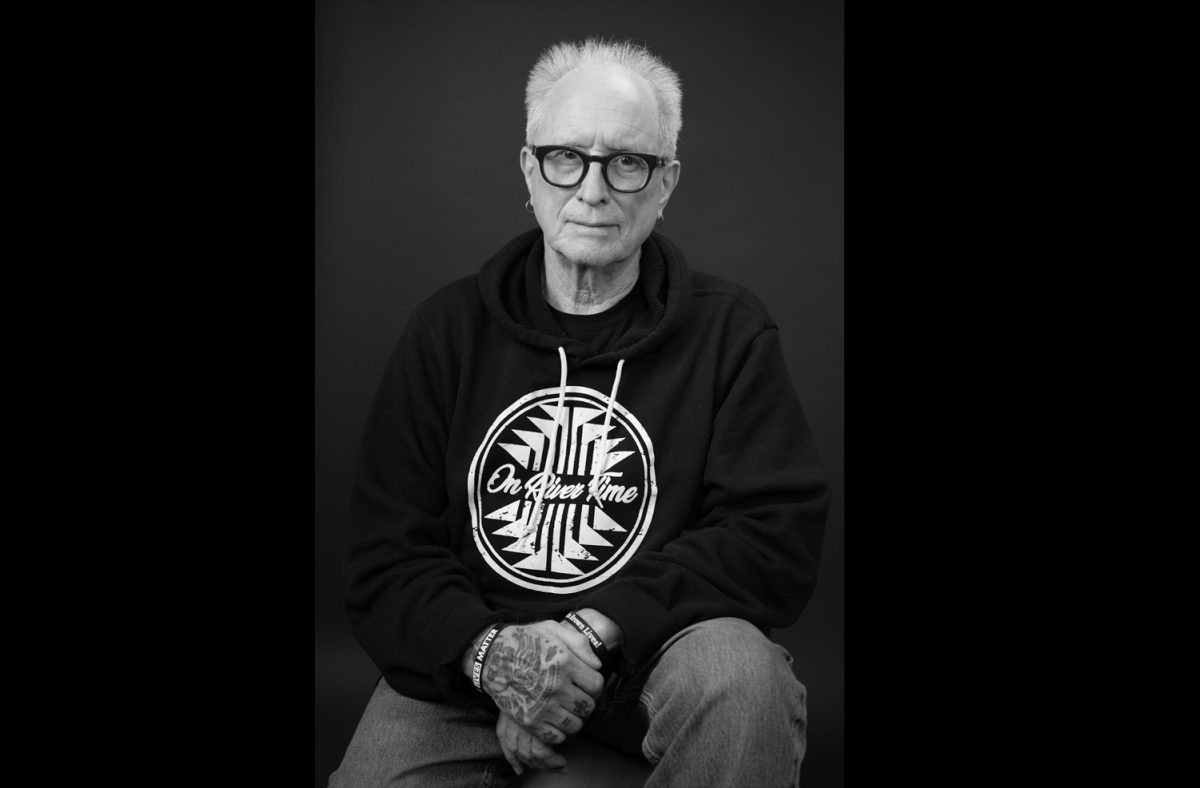

Today, former members of the Weather Underground engage in non-violent activism as educators, lawyers, authors, and organizers. Bill Ayers, a member of Weather’s leadership, the Weather Bureau, is a retired professor at the University of Illinois Chicago and has written extensively about education reform in the United States.

William Charles Ayers was born on December 26th, 1944 to a middle-class, white family in the suburbs of Chicago. He attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and took part in campus protests against the Vietnam War draft. As a college student, Ayers experienced firsthand the contractions of freedom. “One of the paradoxes of freedom is that you never feel more free than when you’re fighting against an obstacle to humanity. When I was first arrested, I was beaten up and put in a police wagon. I was bloody, and on my way to jail. We were all singing freedom songs, and I felt absolutely free,” said Ayers.

The Weather Underground participated in a number of bombing during the 1970s, actions Ayers refers to as “extreme vandalism.” The locations of the bombings include the headquarters of the New York City Police Department in response to the murder of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, the United States Capitol protesting the invasion of Laos, and the Pentagon commemorating Ho Chi Minh’s birthday.

Ayers defines terrorism as “a willful attack, a random attack on citizens – human beings – in order to terrify people into either surrendering or following your political direction.” The FBI outlines a similar definition: “violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups to further ideological goals.”

The Weather Underground abandoned a nonviolent approach to resistance and engaged in extreme destruction of property. They are defined by many, including the FBI, as a terrorist organization. However, the truth is much more complicated.

The United States’ actions in Vietnam abroad and against African Americans domestically falls into both Ayer’s and the FBI’s definition of terrorism. To advance their dominion and anti-communist ideals, the United States committed heinous war crimes in Vietnam, including the infamous My Lai Massacre. Additionally, the FBI’s actions of illegally surveilling and killing prominent African American activists, such as Fred Hampton, could also be classified as “violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups to further ideological goals.”

“It’s certainly true that individuals and political groups and religious groups can be terrorists, but it’s more important to understand that governments can be terrorists,” said Ayers. “In 10 years, every week 6,000 people were randomly murdered [in Vietnam]. That’s terrorism. And so, the U.S. Government was the terrorists and the people who were resisting the U.S. Government were the anti-terrorists.” At the heart of Weather’s resistance was outrage over the daily bombardment and murder of Vietnamese citizens. The National Liberation Front became their heroes, Ho Chi Minh an idol. “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh the NLF is going to win” was a popular refrain.

In addition to the United State’s international “terrorism” in Vietnam, the Weather Underground protested the domestic “terrorism” of police misconduct and brutality towards Black U.S. citizens. By 1969, the FBI’s policies toward Black revolutionaries were increasingly violent and illegal.

Fred Hamton’s murder radicalized many in the Weather Underground. Leader Bernardine Dohrn issued a “Declaration of War” against the United States a few months after Hampton’s death. Weatherwoman Cathy Wilkerson identifies this injustice as what caused her to stay with the organization.

Although benefiting from their white middle-class privilege by not being sought out and murdered, the FBI raided apartments of members of the Weather Underground without warrants and surveilled family members. Dohrn’s parents were mendaciously told to identify their daughter’s body, in hope of scaring them into revealing information about the organization.

Due to FBI misconduct, most charges – which included life in prison – were dropped. After minimal jail time, most members emerged from the Underground, ready to start families and resume a life of non-violent activism.

Ayers is ambivalent about the success of the Weather Underground. They did not end the war; the North Vietnamese did. “I’m not pessimistic or negative because of that, but I think it’s worth noting that the kind of romanticization of the 1960s, that we did everything right and that we won, is not true,” said Ayers. “We didn’t stop the war, and we didn’t end white supremacy.” The importance of 1960s protests was not the full victory of ending the war, but small, individual successes. While their overall success was limited, large anti-war movements and smaller clandestine organizations did make escalation of the war impossible.

Many in the organization also considered just staying alive and active a victory. They fought against the faults of the United States and showed that resistance against a supposedly “all powerful” government was possible. “I’m very, very pleased that I was part of a group of colleagues, comrades, friends who opened our eyes and saw the horror of the war, and the horror of white supremacy and the inhumanity of all that,” said Ayers.

Advocacy Today

Bill Ayers largely identifies himself as an activist today. He teaches at the University of Chicago and leads a class on memoir writing at Stateville Prison in Crest Hill, Illinois. “People say, ‘well you’re from the generation of the sixties,’ and I object because I’m a person right now,” said Ayers. “I mean, I’m not dead yet.”

For example, Ayers has actively followed and participated in protests against the war in Palestine and sees similarities with Vietnam. “This is the issue that’s haunting you, it’s the issue that’s haunting me. While it’s not 6,000 people dead a week, Vietnam was a big country with a lot of people. Palestine has a tiny, little population living in an open-air prison. The scale of murder is horrifying, and it’s equal to what we endured then,” said Ayers.

While university and street protests over the past year have not ended the war, Ayers adopts a similar perspective to that of 1960s activism: optimism of successes and a drive to push forward. Ayers praises student activists for changing the narrative about Israel’s expansion and the United States’ role in the Middle East.

More people are reading about the history of Palestine and more people are becoming politically active. Some are joining groups like Jewish Voice For Peace and Students for Justice in Palestine. Others are donating money to Doctors Without Borders and other humanitarian organizations. One of the greatest effects is the increased discussion and self-education on the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict. “My friend Rashid Khalidi wrote a book called The Hundred Years’ War Against Palestine,” said Ayers. “After October 7th, even though the book was published 3 years ago, it became a bestseller in the New York Times list.”

Due to the attention generated by protestors, people are actively trying to read more and learn more, a process that naturally replaces apathy with humanity.

As someone still active in protest movements, Bill Ayers prefers to take advice from young organizers of today. However, as a teacher and reformer Ayers has some advice on the cycle of activism. “Open your eyes, be astonished, act, doubt, repeat. That to me is the rhythm of activism, and it’s what we all ought to do,” said Ayers.

Freedom and Abolition

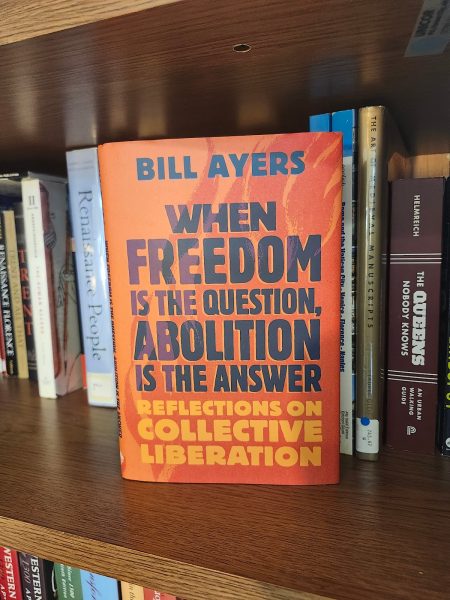

Ayers is currently on a nation-wide book tour for his newest publication: When Freedom is the Question, Abolition is the Answer. In his book, Ayers tackles the complicated paradoxes of freedom.

For example, how one’s individual freedom can harm the collective freedom of a group of people. Ayers writes that individual freedom can be to exploit a community, extract wealth from people, or harm the environment. On the other hand, collective freedom constitutes a group of people rising up against an issue that restricts their freedom. This can be women fighting for reproductive rights or activism from the disabled community leading to the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The way to enshrine collective freedom is abolition. “It’s easy to think of abolition as an erasure, or a doing away with. But the way I talk about abolition is: it’s about world building. It’s about changing things that make oppressive institutions unnecessary or unthinkable,” said Ayers. “Can we build a world where death by execution is unthinkable? Yes. Can we build a world where death by incarceration is unthinkable or where war is unthinkable? I think we can, but it’s a bit of an idealistic stretch. Yet, I think we have to.”

In addition to publications, Ayers continues to engage in education and activism. He fosters free thought and self-discovery through a class on memoir writing at Stateville Prison. Ayers teaches ethics and education at DePaul University and oral history at The University of Chicago. He continues to work with young activists, as an educator, collaborator, and student. “When I was young, I took advice from older people, and now that I’m old, I take advice from younger people,” said Ayers.

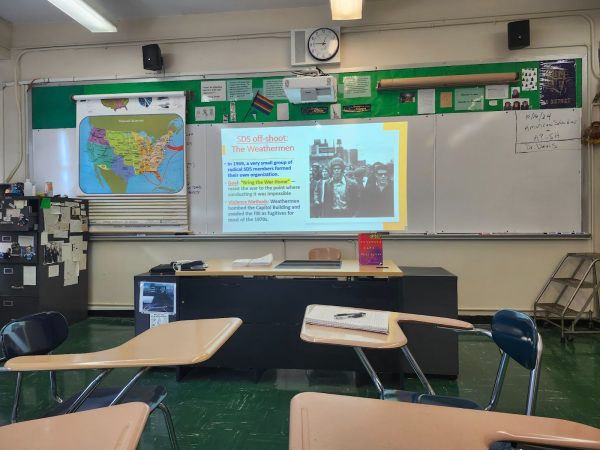

The Weather Underground is an important but untaught subject in American history. It breaks apart the false stereotype of the United States as a country with a peaceful history and little decent following the Civil War. The Weather Underground, and other revolutionary organizations, were actively making war on the United States. People were armed and they were able to successfully evade government suppression.

Even more importantly is the story of the civil rights movement. The “master narrative” of peaceful protests, non-violent sit-ins, and government legislation that fixed everything, is false. Deep into the 1970s groups like the Black Liberation Army and the Deacons for Self Defense were arming themselves against continued police aggression.

A narrative that eliminates dissent is one that fails to recognize the struggles that groups have experienced to attain rights from a hostile government. Ignoring the history of opposition also fails to recognize the ongoing battles for freedom and rights that groups face. The United States is not perfect, yet often perpetuates a revisionist history that serves to cover the country’s darkness. “You should always interrogate history and think: whose voices are dominated, whose voices are missing, what perspectives are serving the powerful, what perspectives are serving liberation,” said Ayers.

Learn history, read books, talk to others, understand new perspectives; that’s the first step in uplifting society. Since 2020, Ayers has hosted a seminar podcast called Under the Tree that focuses on freedom and education. Under the Tree references the Freedom Schools that formed in Mississippi as part of the Black Freedom Movement of the mid-1900s. The podcast encourages the audience to engage with the idea of freedom through poem readings, free writes, guest speakers, and current events.

Once again, Ayers is encouraging people to become their own “Weathermen,” to learn for themselves and take action in their own education and social improvement.

********

I reached out to Bill Ayers a few weeks ago and was able to ask him a bunch of questions. Below is the interview transcript:

Mina Petrova: Could you first please introduce yourself in a way you see fit?

Bill Ayers: Sure, my name is Bill Ayers. I am a retired professor at the University of Illinois Chicago. I currently teach at Stateville Prison, where I teach memoir writing. I also teach at DePaul University, where I teach ethics and education. I teach at the University of Chicago, where I teach oral history. I’ve been retired for 15 years from the University of Illinois, where I was a distinguished professor and senior university scholar, but that was 15 years ago. I’m a teacher mostly, and I write a lot.

Mina Petrova: What do you think are some misconceptions that people may harbor about the Weather Underground?

Bill Ayers: You know. I’m not sure. I don’t know if I can answer that, because I have my own perceptions, and certainly I hear things. But tell me what you think the misperceptions are, or what the perceptions are, and I’ll tell you if they’re misperceptions in my view.

I don’t know if you’ve listened to Mother Country Radicals. Zayd, our oldest son, Zayd Dorn, made a podcast called Mother Country Radicals. He’s now 47, but it’s the story of growing up and being a child of Weather Underground leaders. He ends up interviewing everybody of his generation: kids who are the children of Black Panthers, of the Puerto Rican Independence movement. In those days when there were these militant groups that turned toward armed struggle, here were these kids growing up. Zaid does a really good job of telling the story of the Black Panthers and SDS and the Weather Underground through the eyes of the next generation.

Mina Petrova: Well, one perception is that the Weather Underground was a terrorist organization.

Bill Ayers: Oh yeah, that’s wrong. Glad you raised that. No, that’s not true. And the reason it’s not true is because if you take terrorism to have any kind of stable definition, terrorism is a willful attack, a random attack on citizens – human beings – in order to terrify people into either surrendering or following your political direction. And if you take that as the definition, it’s certainly true that individuals and political groups and religious groups can be terrorists, but it’s more important to understand that governments can be terrorists.

When the U.S. took over the failed French mission in Vietnam, which was around 1965, and ran that enterprise for 10 years. From 1965 to 1975 the American assault, invasion, and occupation of Vietnam was at full power and full heat. In those 10 years, every week 6,000 people were randomly murdered. That’s terrorism. And so, the U.S. Government was the terrorists and the people who were resisting the U.S. Government were the anti-terrorists. While it’s true that the Weather Underground crossed borders of legality, maybe common sense – I mean, you could argue a lot of things, but there’s no way that I see you can define us as terrorists, because we never randomly attacked civilians in order to convince them of a perspective. The U.S. did that routinely in Vietnam, and the scale of it is almost unimaginable.

We memorialized a couple of days ago the anniversary of the World Trade Center attack. 3,000 people were killed. It was a gruesome, terrible, terrorist attack. Awful. 3,000 people were killed, and we’re still honoring it 23 years later. But think about it. 3,000 people were killed. It was terrible. 6,000 people a week were killed for 10 years [in Vietnam], and when you were living through it there was no way to see when or how it would end. So, 6,000 people are going to be murdered next week, and the week after. And why do I call it terrorism? Because the United States just took out a map and just drew lines around large numbers of territory and said “this is a Communist stronghold, anyone in this area is fair game.” And they just carpet bombed the country. And not only did they do it from the air – I think you probably know the story of the My Lai massacre – but the My Lai massacre happened every week. While we make a big deal about it, as we should, because journalists and other military personnel saw the My Lai massacre and reported on it – so that’s why we know about it – it happened every week. Squadrons of young Americans walked into a village and killed everything that moved. What a horror! And what a clear example of terrorism!

What we did, as I say, was illegal. I don’t believe you can say it was particularly violent, although we did turn away from a kind of stance of nonviolence, and we did commit acts of extreme vandalism, is how I think of it. We did more than write slogans on walls. We blew out windows and stuff like that, but we weren’t targeting anybody. We weren’t trying to hurt anybody. We were trying our intention, and I think what we actually did, was to make a screaming cry against genocide and against terrorism. And that’s what we tried to do. I can’t claim that it was successful, but I think that that’s what we set out to do, and I don’t think of that as terrorism at all.

Follow up and challenge me if you want to.

Mina Petrova: Another misconception or conception people have is on the topic of how successful the Weather Underground was. What do you think your most successful action was? Do you think breaking away from the SDS and larger protests in general was a justified method?

Bill Ayers: I don’t think that I can make any claims of success. When I was first arrested opposing the war in Vietnam, which was in 1965, and then was arrested a dozen times over the next several years in militant, nonviolent demonstrations – we set out to end a war. As we became more aware of what the system was, that it was a war-making system, we set out to end the cause of war. So, from 1965 on, our goal was to end the war in Vietnam. We didn’t do it, so I don’t think you can look back on it and say, “that was a success.” We didn’t end the war in Vietnam, did we? We didn’t stop the killing. In many ways, even though we convinced, by 1968, a majority of people that the war was wrong, and there was a super majority of people in the world who knew that the war was wrong, we still couldn’t stop it. That’s what drove us to try other things.

I’ll give you an example. In my own family, I’m the middle of five children – in my birth family – and by 1967, all five of us were deeply opposed to the war in Vietnam. But we couldn’t stop it. That created a crisis for democracy and a crisis with the antiwar movement. One of my brothers joined the Democratic party and tried to build a peace wing. One went to Canada as part of the great migration away from war. One went and worked in the factories in an attempt to organize the industrial working class in the Midwest to oppose the war. One went to the communes. And I did what I did. None of us were brilliant. None of us ended the war, but none of us were crazy either. We were doing our best to figure out: how do you respond to a government when we thought (in 1965) what we have to do is convince the majority to oppose the war. We did that and we thought we had won by 1968, but the war didn’t end. It ground on and on, and every week 6,000 people would be murdered with no end in sight. So, what do you do? That was what we were up against.

Back to the question of success, I think it’s too early to tell. We didn’t end the war. I’m not pessimistic or negative because of that, but I think it’s worth noting that the kind of romanticization of the 1960s, that we did everything right and that we won, is not true. We only won in retrospect. We didn’t stop the war, and we didn’t end white supremacy. That was the other thing we set out to do, and of course we’re still in a mess. We both still have a white supremacist society. We still have war and Empire as a major part of our politics. I don’t say that as a kind of depressed or negative thing, I say it because we’ve got to get busy and be stronger, smarter, harder, you know all those things. More generous, more forgiving of each other.

But there’s one other thing I would say, which is at one point a colleague or friend of mine wrote a piece in which she said “the Weather Underground didn’t shorten the war by 5 minutes.” And, I laughed about that, and I called her up, and we talked about it. But I laughed about it because she worked for The Nation magazine and I said, how many minutes did The Nation magazine shorten the war by? None of us ended the war, the war was ended by the Vietnamese. You’ve probably seen pictures of the Americans fleeing in helicopters off the roof of their own embassy. So, none of us ended the war.

We did do some things, and I think we were successful in some ways. We limited the options of the war makers. There were written plans to drop tactical nuclear weapons on Vietnam. There were written plans to destroy the elaborate dike system in the North and flood the country. They didn’t do those things. Partly, it would have created a firestorm in the world because the world opposed the war in Vietnam, the American war in Vietnam.

But success is hard to measure, and what it brings to mind is Zhou Enlai, who was the Premier of China after the Revolution. He was asked by a French journalist in 1947, was the impact of the French Revolution of the 18th century on the Chinese Revolution of the 20th century? Zhou Enlai thought about it for a minute, and he said, “it’s too soon to tell.” I love that answer. The reason I loved it was because as Americans, we think that we ought to, for example, pay attention to polls. How many people think the Ukraine war is worth supporting? We’ll take a poll. But it’s way too soon to tell. It’s way too early. And I also am skeptical of causal claims, “I did this, and it caused that.” I think humanity is too complicated and social movements are too complicated. But the one thing I would say is that social movements are made up of human beings: flawed, contingent, messed up in many ways. Human beings do their best to make the kind of social movements that we can make. But we have to always remember that while human beings make history, we don’t make history in the conditions of our own invention. We make history in the conditions that are given to us.

I’m very, very pleased that I was part of a group of colleagues, comrades, friends who opened our eyes and saw the horror of the war, and the horror of white supremacy and the inhumanity of all that. I’m glad that we put our shoulders on history’s wheel, but whatever that was, it was a prelude to what we have to do now. And when I say we, I mean you and me. People say, “well you’re from the generation of the sixties,” and I object because I’m a person right now. I mean, I’m not dead yet. I plan to be on the barricades, which I was a couple of weeks ago, and I plan to be there. I’m a member of your generation, and you’re a member of my generation. We’re both living now, we’re both looking uneasily at the world, trying to figure out how to act in a way that can make a difference for the benefit of humanity. You’re thinking about that. I’m thinking about that. And we can think about it together.

Mina Petrova: On the topic of right now. I think a lot of people see connections with the situation in Palestine and what occurred in Vietnam. A lot of people are looking uneasy at the amount of death, while maybe not as much as in Vietnam, occurring right now. How do you think the university protests parallel SDS? Do you have any advice for protesters today?

Bill Ayers: You know, I’m glad you raised this. This is the issue that’s haunting you, it’s the issue that’s haunting me. While it’s not 6,000 people dead a week, Vietnam was a big country with a lot of people. Palestine has a tiny, little population living in an open-air prison. The scale of murder is horrifying, and it’s equal to what we endured then.

I have to say first, that the Palestinian community and groups like Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace – the dissenters – have done the most remarkable thing I’ve ever seen. In 3 months, and now we’re 11 months into this war, but in 3 months these dedicated, courageous, compassionate, thoughtful people changed the narrative in this country about what Israel was and what the U.S. role was in the Middle East. That’s a remarkable accomplishment.

But what kept staggering me as it unfolded was that throughout this they were lied about and people made stuff up, and they’re still making stuff up, “they’re antisemitic; the encampments are antisemitic.” The encampments here at the University of Chicago are largely Jewish. I mean the idea that it’s antisemitic, that there’s only one way according to these guys to be a Jew and that is to be a Zionist, that’s not true. The whole tradition of the Jewish people includes a lot of secular, progressive left wing Jewish people. So, anyway, with all the lies told and all the brutality that was brought against them, they succeeded.

They also succeeded at the Democratic National Convention. The people who were involved in the demonstrations, myself included, many people were disappointed that the uncommitted person didn’t get to speak. There were uncommitted delegates to the National Convention, and they pushed and pushed and pushed to have one speaker from the stage, and the Democratic party wouldn’t allow it. You could say, that’s a defeat. But in reality, Gaza was on everybody’s mind. The fact that they wouldn’t let an uncommitted delegate speak, spoke to their fear and their cowardice in this moment. Fear about taking on the truth about what’s going on there. I think, young people, the encampments, high school kids, people who blocked the bridges in New York, people who blocked the airport in L.A., they made a significant difference. Has it translated yet into policy? No. Has it stopped the war? No, it hasn’t. But this change in narrative happened in 11 months, or 3 months is really what accomplished it. We should be very, very proud of that, and now we should push on. We should push on into the fall. We should push on and make our demands stronger, more convincing, more compelling. But I think it’s important to start by saying the movement of the last 11 months has been a roaring success in terms of changing the narrative about Israel and about Palestine and about the American role in the Middle East. That’s huge. Changing the narrative is a huge part of movement building, and we’ve done that. I think we should be very, very proud of ourselves for that.

Now, as far as advice. I don’t really have advice. When I was young, I took advice from older people, and now that I’m old, I take advice from younger people. I work very closely with several terrific youth groups here in Chicago. But I do think that pressing on is always important. Or another way of saying it is: in order to be a moral person in this society, in order to be an activist or an organizer, you have to follow a certain rhythm. Part of that rhythm is opening your eyes and seeing the world large, seeing things as they are. And you can’t do that once, because the world is dynamic and ever changing. So, we have to open our eyes again and again. Always be learning, always be studying, always be trying to see a larger perspective. Talk to more people, talk to more strangers. If you don’t open your eyes and pay attention, you can’t make a moral or a smart activist decision. But after you open your eyes, you have to be astonished. You have to be astonished at the beauty and the ecstasy in every direction and you have to be astonished at the unnecessary suffering that people visit upon one another. Then you have to act. You have to do something. You can’t just sit on your couch…I think what’s required is that you act at whatever the known demands of you. And then the fourth step is to rethink. Did I do it right? Is there more I could have learned? Is there more I could have done? And then start over. Open your eyes, be astonished, act, doubt, repeat. That to me is the rhythm of activism, and it’s what we all ought to do.

Mina Petrova: I think something that may discourage many is the cost of protest or of activism. Some people may be afraid of being labeled antisemitic or a terrorist. Why do you think people should engage in these protests, even though they might risk censorship, or they might risk expulsion from universities?

Bill Ayers: You know, as Frederick Douglass said, “There is no progress without struggle.” There never has been, there never will be. There’s always a cost.

We should be generous and graceful with each other because we’re flawed, we’re imperfect. We make mistakes, but you need to have your eye on the humane idea that everyone is a human, everyone has a right to live, everyone deserves everything they need for a life of dignity. If you hold on to your ideals in that regard, yes, you’ll take risks, yes, you’ll make mistakes, yes, you’ll pay some price. But in the end, what you gain is a sense of a purpose in your life.

I mean, this is one of the interesting things everybody believes. They believe that they would have been a hero looking backwards. We all would have been on the Selma bridge. We all would have been sitting in with SNCC. We would have all protected Anne Frank. We would have all tried to assassinate Hitler. We would have all been with John Brown or Frederick Douglass. It’s easy to look back at slavery and say that was wrong. But imagine yourself living in 1845 or 1850, and whether you were an enslaved person or a free white person, imagine you’re looking at the world and you’re saying: “I think I’ll stand up and speak out against slavery. I’m gonna act against that horrible institution.” If you did that, you would have been against the founders, the constitution, the law, the Bible, your preacher, your parents, your neighbors, your friends. But okay, we’re all good people now, so of course, we’d all have had that courage. But that’s not good enough.

What is unacceptable today will not always be so in the future. And you’re right to raise Gaza as one of the clearest examples of a staggering inhumanity, a preannounced genocide. They said they were going to commit genocide. They said it on October 8th, they said it on October 9th. They said we will starve them, will make Gaza unlivable, we will not allow them water or medicine or fuel. And they did it. That was a preannounced war crime, a preannounced genocide. So, you’re right to raise it. And then the question is, what should we do? The kids at the University of Chicago and the kids at Columbia University, they decided it was worth the risk to stand up for humanity, whatever the cost. I salute them. I think they’re brave and wonderful. The only hope we have is each other, arm in arm, heart to heart. That’s our only hope. It’s not appealing to power to treat us more gently. That won’t work. But I am convinced that those who built the encampments, those who built the resistance, are not only on the right side of history, but they’ll be absolved, and very soon. Then the people who didn’t build the encampments will be the ones who were weak and unengaged. They missed their moral moment.

I think the universities have shown that they have no moral core. I mean, what’s staggering to me, Mina, is that the prestigious presidents of these prestigious universities could not go to Congress and speak to the know-nothings and tell them what academic freedom means. Academic freedom is way more than freedom of speech, way more. And here they were bowing down to these idiots in Congress. How dare they? Every graduate student here at the University of Chicago could have defended academic freedom better than any President of the University did in that crucial moment, and I think that the University should be ashamed. What the University could have done incidentally – at Columbia or here or anywhere – is to say that these encampments have brought an urgent issue to our front door. And since we’re all about education, we’re all about the freedom to think and the freedom to teach and the freedom to learn, let’s have the whole university discuss this. Let’s not isolate these kids and call the cops. Let’s instead have a conversation. That’s all the kids were asking for, anyway. The universities didn’t have the courage to do that. So, when we look back on this, you and me, we’re going to say that those students at the University of Chicago, those students at Columbia, those students at Northwestern and Harvard and Yale, they had the moral core, and their universities failed them miserably. And I think that’s what history, and history very soon, will conclude.

Mina Petrova: Yes, and even in high schools there is a fair amount of censorship on the topic of the war in Palestine.

Bill Ayers: Yes, you’re right. I know a lot of high schools, and actually, I know a couple of kids about your age in Los Angeles who are really suffering because they’ve been accused of antisemitism. In this case, this is not true of them, but they’ve been accused. And, the reason they’ve been accused is because they raised the question of what right does Israel have to be a settler-colonial country, killing people freely in the West Bank and keeping Gaza as an open-air prison for 20 years.

See, this is one piece of advice, now that I think of it. One of the things we should all be doing is studying more, learning more, and taking this as a teachable moment. So, my friend Rashid Khalidi wrote a book called The Hundred Years’ War Against Palestine. After October 7, even though the book was published 3 years ago, it became a bestseller in the New York Times list, because it really gives you an historical context of what’s going on.

The other thing is, get with Jewish Voice for Peace. Jewish Voice for Peace is Jewish people and it’s not antisemites. They refuse – very vigorously –they refuse to say, every Jew who’s a worthwhile Jew is somehow a Zionist. They are not Zionists, but that doesn’t make them not Jewish right? And there’s all kinds of traditions in Judaism and in Jewish culture which are traditions of resistance.

Mina Petrova: Yes, and you also had a lot of people in The Weather Underground, like Mark Rudd, who were from Jewish families.

Bill Ayers: Yeah, well, not all of us. But Bernadine [Bill Ayers’ wife and former leader of the Weather Underground] is Jewish. Mark Rudd is Jewish. Eleanor Stein is Jewish. Yeah, I mean, half of us were Jewish.

There are all these different things that are going on that make us feel weak in opposing this war. One is the accusation of antisemitism. The other is the constant refrain: Israel has a right to defend itself. I mean, it’s so crazy because of course, that’s true. Of course, October 7th was a terrible, terrible crime, and abducting people is criminal. It’s criminal in international law. You can’t do it. You can’t kill randomly. If I go out here on 57th Street, and I get mugged, I have a right to defend myself. But, I do not have the right to take an automatic rifle and kill everybody on 57th Street because I was mugged. I mean, it’s insane, and yet it’s said again and again.

The other kind of tropes that we hear that we have to find out how to defeat are when people say: “well Israel you just bombed 6 hospitals.” And they say: “yeah but they were hiding Hamas fighters.” That is the oldest lie in the book. That’s what was said in Vietnam all the time. The U.S. army would kill an entire village, and then say: “yeah but there were Vietnamese Communists hiding there.” That doesn’t give you a right to murder 139 women and children. Are you crazy? That’s what’s going on in Gaza. The same tropes are being thrown out again and again. “We have a right to defend ourselves. They’re hiding terrorists.” Think about it! I mean, they’ve bulldozed the whole damn country, and they’ve killed 50,000 people. How can that be? How is that a defense? How is saying, we’re defending ourselves, a defense of that. The U.S. did the same thing. Razing Vietnam to the ground was somehow defending America. In what way do you go 10,000 miles away to Vietnam and drop more bombs on it than were bombs dropped in World War 2? In what way is that defending America? In what way is a trillion-dollar military budget a self-defense budget? It’s just a lie, and we have to expose those lies. One of the ways is to study, think, get into debates, call for a teach in, call for a film series. You know, those are the things you can do. You can organize.

Mina Petrova: You’re also currently an educational reformer. What do you think needs to be changed in the educational system?

Bill Ayers: Well, that’s a big, long, complicated thing, and I’ve written a lot of books about it. But I can say briefly that every educational system in the world reflects the social system. So, if you go to apartheid South Africa, of course you had wonderful schools for the minority white kids. You’d have a class with 13 students in it. And the African kids had a class with 75 kids in it. The white kids had a beautiful lab and a beautiful theater, and the black kids had a building with the roof falling in. So, apartheid was reflected in the schools, right? And if you go to a feudal country like Saudi Arabia, you’ll see in the schools a kind of feudal arrangement. If you went to Nazi Germany or fascist Italy, while they had great scientists and artists and athletes, the hidden curriculum in all their schools was obedience and conformity. That’s how they created a society where people can look the other way while people are marched into ovens. It all has to do with the schools. What I’m saying is, schools reflect society.

In a free society obedience and conformity would not be the rule of the day. The rule of the day would be initiative, courage, imagination, the arts, and so on. I think you could look at something like Bronx Science and say: “are we free, as free as we think we are?” In a free society the kinds of things you would foreground are people’s initiative and agency. You’d be underlining that at all times. Whatever subject you taught, you would be teaching a kind of tolerance for messiness, a kind of acceptance of nonconformity, an appreciation of diversity and different opinions. But that’s not what Bronx Science looks like, mostly. I mean, you’re better off than most because you’re in a very privileged school. I mean, the biggest problem with privilege, this is in parenthesis, but the biggest problem with privilege isn’t that it’s something to be ashamed of or feel guilty about. The biggest problem is that privilege blinds you to other people. You begin to think, my perspective is the real perspective. So, men don’t see clearly what women are suffering. White people don’t see clearly what Black and Brown people go through. It takes some waking up to.

The problem with privilege is anesthetization, and the answer to that is to become more aware. To become allies and partners with people who are not like you and to learn from them. But my basic idea is that in a really good school, in a free school, every kid would get these messages: “You have every right to be here. You belong here. We are diminished if you’re not here.” And most important: “you need no one’s permission to interrogate the world. You don’t need my permission. You don’t need your parents’ permission.”

This is worth underlining today, because of all the restrictions in schools right now. For example, posting the 10 Commandments in a public school in Alabama…This comedian said we should post the 10 Commandments in every American uterus, so the kids get the right start. What kind of insanity are we living through when books are being banned and you’re told, these are things that are too dangerous for you to read. Free people read freely. You need no one’s permission – not the government, not your teacher, not your parents – to interrogate the world. So, interrogate away. That’s freedom.

Mina Petrova: So, I believe this is rare for most history classes, but I had a pretty exceptional American history teacher, and we actually learned a little bit about the Weather Underground. How do you think your history should be taught?

Bill Ayers: I don’t know. You know, I’ve never really thought about it. Just like I’ve never thought about our legacy, I think it’s too soon to tell. I think there was a movie called The Weather Underground that Sam Green and Bill Siegel did. What motivated them was that they were in high school, and they’d never heard of it. And then they found out about it, and they said: “Wait, why didn’t we learn that in school? Why didn’t we learn about the rebels and the radicals?” I think that that’s worth asking. What that led them to was creating a series of films that they called The Hidden History Project. It’s about what’s being hidden from you, since you don’t usually know the whole story about what perspectives are missing. If you have a school – and it sounds like your history class was like this – that’s worth its salt in a free society, it emphasizes: what are we missing? What perspectives are we missing? Whose story is being told? Whose story is not being told?

The killer example of that is the history of slavery. I’m 80 years old now, so when I was in school, slavery was taught as an unfortunate something that happened, but not the reality of what it was. But, when I was a young adult, great historians and great scholars and great activists uncovered the slave narratives. They uncovered the voices of the enslaved people. Now you can’t possibly teach about slavery without hearing those perspectives. That’s great.

When we talk about American wars, we should always talk about the dissidents, the ones who wouldn’t fight, the ones who refused, the ones who didn’t go along with the project of colonialism, and so on. I think that we are also telling a truer story today about native peoples, for example, than we’ve ever told in the past. I think that’s a great thing. And so, I imagine because the people who opposed the war in Vietnam in this country were right – we weren’t wrong – I think it’s worth noting that there were people at a time of mass murder, who stood up against that. I think that’s worth knowing about not just us, not just this little organization, but the movement as a whole.

And similarly, I think the story of the black freedom movement of the fifties and sixties and seventies is a critical story to tell. But don’t believe the nonsense about: there was once upon a time, a bad moment in America, when in the South, black people were discriminated against. And then a saint came along. He had a dream. He gave a speech. And now we’re all better. That’s just nonsense. That’s a narrative that is easily dislodged. The true story includes the Deacons for Self-Defense. It includes the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. It includes the Black Panthers. It includes people you’ve never heard of, and the Deacons for Self-Defense is one example.

I’ll give you an example of the Deacons. If you ever dig up this picture of Martin Luther King during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, he’s in his house, and he’s standing at a window, and behind him are two elderly black men with shotguns sitting in rocking chairs. And you see the picture and say, “what? wait? Martin Luther King? No way.” He had an armed guard. The Deacons, people in the South, they were armed. I mean black people were armed to, partly to hunt and partly to protect themselves. There’s a wonderful book by a friend of mine named Charlie Cobb, who was a SNCC activist. The book is called This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed. It’s the story of how these kids came to the South to organize people to vote. They stayed in the homes of sharecroppers, and every sharecropper was armed. And so here we are. And, SNCC is called the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, but Charlie called it the non-student non-nonviolent non-organized non-committee, or something like that, because he said that none of that was true. Charlie says, “we were called SNCC, the Student, Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, but we weren’t a committee. We weren’t coordinated. We weren’t nonviolent. And we weren’t students.” So, that’s kind of funny.

Anyway, all I’m saying is that, I don’t have a strong feeling about the organization, but I do think that people should be aware that history is complicated and multi-layered. You should always interrogate history and think: whose voices are dominated, whose voices are missing, what perspectives are serving the powerful, what perspectives are serving liberation.

Mina Petrova: You have a new book coming out, When Freedom is the Question, Abolition is the Answer. Can you tell me a little bit about what the book is about?

Bill Ayers: It’s a set of essays. The subtitle is Reflections on Collective Liberation. The idea is that freedom is applicated on our American minds. We’re all for freedom. The Democrats are for freedom. The Republicans are for freedom. The killer example that’s important to remember is that the Civil War was fought for freedom, right? But in your perspective and in my perspective, it was fought for the freedom of the enslaved workers. But if you read the documents, the Confederacy was fighting for freedom. They seceded from the United States because they wanted freedom. Freedom to what? Freedom to own other human beings! So, if freedom is that contested as a concept, let’s get into it. Let’s think about it in a new way. What I try to do is I try to unpack this very, very complicated concept: freedom.

I try to talk about the paradoxes of freedom. The ways in which individual freedom is different from social freedom. Individual freedom could be the freedom to build an oil rig in the middle of a wheat field or the freedom to exploit people and extract wealth from them. That’s freedom. Or it could be collective freedom. An example is women saying, “we have the right, as women, to control the integrity of our own bodies.” That’s collective freedom. That’s a group of people self-identified, saying, “we want to be free.” It’s always the case that social freedom comes about when people see themselves as part of a community or part of a public. I’ll give you another example. There’s a wonderful film that you should see, I think it’s on Netflix, called Crip Camp. It’s a documentary about the growth of the disability rights movement. There was no such thing as the disabled community when I was growing up. There were just people living in the back room with their families. There was no concept of a public called “the disabled.” But this film documents how in the 1970s, a group of people got to know each other and got to see that they were facing the same levels of discrimination, even though they were facing their social problems as individual problems.

You could probably easily grasp this concept. I don’t know if you have any old people in your family or any young kids. Childcare in this country is a social problem, but every family experiences it as an individual problem. Taking care of the elderly is a social problem, but it’s experienced as my problem. How am I going to take care of my parents? So, these disabled people they all found themselves – a critical mass of them – at Berkeley University of California. At Berkeley, in the 1970s, they decided to take action. They said: “you’re facing that issue, well, I’m also facing that issue. Let’s do something about it.” And this is long before there were ramps. One of the cool things they did as activists is that they went out one night and they poured concrete on all the crosswalks, and they made ramps for their wheelchairs. And they did it, they’re all wheelchair bound, and they mixed cement, and they poured concrete, and it was illegal, and some of them were arrested. But what a great action! And then they said: “we brought a public into being.” And that led to lobbying Congress and getting laws passed and getting The People With Disabilities Act passed. I mean, what a great step forward for humanity. We suddenly saw that in our human family, some of us need wheelchair lifts on the buses. And now we accept that. Although some people still grumble: “why should I pay for a wheelchair lift, I’m not in a wheelchair.” Get over yourself! We’re part of the human community, you know.

So, when I talk about freedom. That’s what I’m talking about. I’m talking about people who are facing an obstacle or a wall or an unfreedom, then collectively moving against that wall. That’s part of what I’m talking about. So, freedom is a complicated concept, and I get into it in a lot of different ways. One of the paradoxes of freedom is that you never feel more free than when you’re fighting against an obstacle to humanity. I describe this in one chapter [of Bill Ayer’s memoir Fugitive Days] when I was first arrested. I was beaten up and put in a police wagon, and I was bloody, and on my way to jail. We were all singing freedom songs, and I felt absolutely free. I felt ecstatic. But I was in a police wagon, you know. So that’s a paradox, right. But there are a lot of those in history.

The second concept is abolition, which is equally complicated. It’s easy to think of abolition as an erasure, or a doing away with. But the way I talk about abolition is, it’s about world building. It’s about changing things that make oppressive institutions unnecessary or unthinkable. In 1845, slavery was entangled in every aspect of our country, and it was the basis of the wealth of the country. So, think about the abolitionists of 1845. They could not imagine a world without slavery, but they knew they had to get there. In their activism, in their organizing, in their advocacy, they began to create a world where slavery was unthinkable. What a great thing! We have the same responsibility. We have the responsibility in some States in this country to create a situation where the death penalty is unthinkable. When I think of abolition, I think: can we build a world where prisons are not necessary? I think we can, and I think we have to. Can we build a world where death by execution is unthinkable? Yes. Can we build a world where death by incarceration is unthinkable or where war is unthinkable? I think we can, but it’s a bit of an idealistic stretch. Yet, I think we have to. So that’s my work, freedom as social and collective abolition, as world building.

“Open your eyes, be astonished, act, doubt, repeat. That to me is the rhythm of activism, and it’s what we all ought to do,” said Bill Ayers.