The Tale of Genji (源氏物語), also known as the Genji Monogatari, is widely regarded as the first full-length novel in the world, spanning 54 chapters (roughly 1 million characters in the original manuscript, over 300,000 words and 1,200 pages in the English translation). Throughout its story, The Tale of Genji explores court intrigue and complex tapestries of human relationships from the Heian era. It was written in Early Middle Japanese, composed of Chinese (called kanji in Japanese) and two other scripts derived from Chinese characters, the basis to the modern Japanese language today. This author is one of the most celebrated literary luminaries in Japan, as seen in countless modern interpretations of The Tale of Genji, a yearly festival dedicated to their name, and the first 2000 yen bill showcasing the author and a scene from The Tale of Genji. This sprawling triumph of human ingenuity, however, was not written by a high-ranking nobleman like many in the present day may first assume, but by a woman whom we only know by her sobriquet, Murasaki Shikibu.

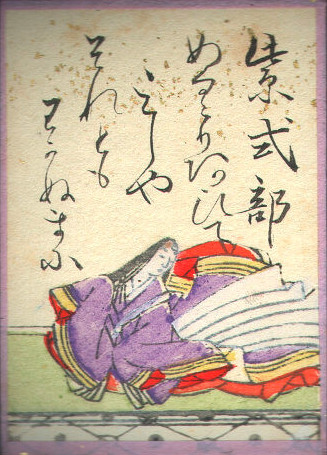

Murasaki Shikibu was born c. 978 CE during the Heian Era (794-1185) to a lesser branch of the powerful Fujiwara (藤原) clan who comprised most of the upper positions within the imperial bureaucracy. Her father, Fujiwara no Tametoki, held a position within the Shikibu-sho, or the Bureau of Rites. As it was customary during this era to refer to court ladies by the position of one of her relatives, the second half of her sobriquet, Shikibu, was derived from her father’s position. She may have become known as Murasaki from one of the heroines of The Tale of Genji, or from the purple (murasaki) wisteria flower, fuji (藤), the first character of the Fujiwara name. His position within the Bureau of Rites required Murasaki Shikibu’s father to be knowledgeable on Chinese Confucian classics. It was because of her erudite father and grandfather that she gained a passion for poetry and Confucian classics.

Women within the imperial court during the Heian era were expected to practice skills considered “feminine arts,” such as embroidery, painting, and calligraphy. By contrast, men were expected to study history and Chinese literature, such as Confucian classics, to prepare them for future positions within the court. Because of this, women were heavily discouraged from learning Chinese and were expected to simply learn the Japanese katakana and hiragana scripts.

Murasaki Shikibu, however, educated herself in poetry as well as Confucian texts, mentioning in her diaries how she studied Chinese by listening to her brother’s lessons from outside the door. In fact, her command of literature exceeded that of her brother’s, delighting her father by composing masterful poems and quoting from historical literature. It was this skill in her craft that allowed her to later become a lady-in-waiting and tutor for the future empress, Fujiwara no Shōshi, also known as Jōtō mon’in.

The Tale of Genji was reportedly completed around 1010 CE during her time as the lady-in-waiting of the empress, but writings in her diaries suggest the work had been in progress for quite a long time, estimating around a decade.

The Tale of Genji incorporates around 800 waka, 5 lines of poetry that follow a 5/7/7/5/7/7 syllable structure, similar to the much more widely-known haiku, which uses a 5/7/5 structure. Murasaki Shikibu wrote each waka from the perspectives of characters, seamlessly weaving in poetry that are not just works of masterful craft but also contribute heavily to the reader’s understanding of their emotions. In an article for The Association of Asian Studies, Sonja Arntzen writes, “Mood and setting are far more central to this work than one expects in the traditional western novel (unless one thinks of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past.)…The poems are focal points in most dialogue and create pauses in the momentum of the story line that allow the reader to identify deeply with the characters’ feelings.”

Waka often focus on capturing emotions in the moment rather than explaining them. The protagonist of the novel, Genji, writes the following waka after the death of one of his wives, Murasaki. In his grief, he tells his lover, Akashi, of his contemplation towards taking religious vows, meaning he would have to devote the rest of his days to Buddhism and practice celibacy. For the amorous Genji, notorious for his romantic affairs, this would be a stark change. During their conversation, Genji considers spending the night with Akashi but eventually decides against it. He sends a waka to her the following morning:

“Naku naku mo / kaerinishi kana / kari no yo wa / izuko mo tsui no / toko yo naranu ni.”

Or, in English, “Crying, oh crying / Like the wild geese / I make my way home; / but this passing world / holds no resting place eternal.” (Translation by Edward G. Seidensticker, from The Tale of Genji, New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1992.)

Waka often feature symbolic themes of nature, and the geese showcased in this poem are popular in Chinese and Japanese poems. Here, the migratory geese symbolize the changes in the world, the shifting seasons, and, therefore, partings within Genji’s life. In the poem, “toko yo” is a play on words: “toko,” or place, means bed in this instance, and “toko yo” has the same pronunciation as tokoyo, the afterlife. Genji laments how his lovers leave towards the “eternal” afterlife like migrating geese, unable to keep them with him in his bed. The geese can also represent Genji himself, who is “crying like the wild geese” while heading home with no “resting place.” Murasaki Shikibu portrays Genji’s longing through complex symbolism and layers, all in a few short lines.

As a Japanese-American, it’s hard to not admire — and envy — Murasaki Shikibu for her masterful command of language. I find myself mirrored in her life, or, rather, perhaps her life is reflected in mine.

Similar to Murasaki Shikibu, I never received a formal education in Japanese, so I am less fluent than my peers who were born and raised in Japan. For a long time, I’ve struggled with my identity, feeling as though I am “not Japanese enough” because of my upbringing. The knowledge I have of my own culture is mostly passed onto me through second-hand experience, either from my parents speaking of their childhoods or through media depicting a Japanese childhood.

Despite her ubiquity in Japan, I never knew about Murasaki Shikibu until I learned about her in my Freshman Global I class at Bronx Science. Learning that I had simply not known of such a prominent figure had shocked me.

Yet, as I learned more and more about her and the core concepts in The Tale of Genji, my understanding of identity shifted.

The Genji Monogatari can be uncomfortable to read in 2024, especially for women. Genji is a son of the emperor born of a low-ranking consort known for his charm. Despite being married, he pursues other women while disregarding the ramifications of his actions (going so far as to have an affair with his stepmother, which they have to keep secret lest their biological son, the later crown prince, be affected). In many of his attempts at seduction, he uses coercive measures, chillingly similar to the experiences of sexual assault victims in the present day.

Murasaki Shikibu does not shy away from the bad and the ugly, and portrays relationships realistically — all while centering the feelings of both men and women. Her work contributes largely to historians’ understanding of court culture, even if the political aspects featured in the book are not completely accurate. The Tale of Genji reflects Murasaki Shikibu’s understanding of her own culture, of the importance of recognizing your emotions in the moment, and learning to grow from them. As Arntzen states, “The heart of the novel is the wonder and poignancy of human emotion, particularly as it is experienced in the infinitely varied forms of relationship between men and women.”

A persistent theme in the Genji Monogatari is something called the mono no aware, literally translating to “the pathos of things.” It is a concept that describes the transience of things in life, the feelings of sadness and tenderness that are evoked from it, “the poignancy of human existence.” Transience is not accepted but is still appreciated, especially in nature. This is a concept often seen in Japanese culture. Take, for example, cherry blossoms.

Cherry blossoms bloom in late March to early April, right in time for the Japanese school year to end in March and for the next one to begin in April. As such, they are associated with youth and beginnings but also with farewells. No one wants to see cherry blossoms fall, but they seem all the more beautiful because of their transience. This bittersweet duality of cherry blossoms is similar to how Murasaki Shikibu depicts love in the Tale of Genji. Many of Genji’s romances are short, but with each romance that Genji experiences, he grows and learns from them.

Mono no aware can be applied to almost anything, including cultures. No culture will last forever; that is a sad, but true fact. This does not mean, however, that we should not strive to celebrate our cultures. My understanding of Japanese culture may never be “complete” in the traditional sense, but my experiences with it, through food, tales, and music, are all invaluable. Sharing our stories and commemorating our existence should be one of life’s greatest pleasures, much in the same way Murasaki Shikibu must have felt when writing The Tale of Genji.

The Tale of Genji, a sprawling triumph of human ingenuity, was not written by a high-ranking nobleman like many in the present day may first assume, but by a woman whom we only know by her sobriquet, Murasaki Shikibu.