It starts off with a beautiful soft harmony of voices, gradually coming together to form a perfect polyphonic ensemble. As the notes weave through the air, Carlo Gesualdo’s sixth madrigal invites listeners into another realm where emotion goes beyond the typical style of his time.

I’m listening attentively, trying to paint a portrait of the world that Gesualdo is envisioning in my own head. As I listen to the sound of gentle, holy voices turning into a labyrinth of tonal shifts, I cannot help but wonder who was the composer, the genius who constructed this masterpiece.

Carlo Gesualdo was a notable composer during a crucial period for classical music, and his style reflects it. He was born on March 30th, 1566 in Venosa, a town inside the providence of Potenza, Italy. Italian culture and the arts were booming all throughout the region, a period of time known as the Italian Renaissance. It lasted from 1400 to 1600 and was a time where traditional vocal and choral music flourished.

Gesualdo was born into a prominent noble family. In 1452, the title of Count of Conza was granted to Sansone II, Gesualdo’s ancestor. This title confirmed the nobility status of the family, leading them to become important figures in Venosa. Gesualdo’s father, Fabrizio II, married Pope Pius IV’s niece, Geronima Borromeo, in 1561, which caused the family line to inherit control over the principality of Venosa granted by King Philip II of Spain.

Gesualdo, named after his uncle, Carlo Boremo, was the second born son of the Gesualdo family. Borremo was the son of Pope Pius IV, thus earning him a noble reputation. He was canonized in 1610, meaning that he was officially recognized and declared a saint by the Catholic Church, becoming a holy individual worthy of public worship.

There are very few records that tell historians about Gesualdo’s early life, but it’s known that he did not live a very cheerful childhood. His mother died when he was 7 years old and he was left under the care of his uncle Alfonso, the Archbishop of Naples. Gesualdo, however, grew up thinking he did not have to worry about inheriting the estate and becoming an heir. However, in 1584, his brother Luigi died, leaving Gesualdo with responsibility over the family line.

This marked a major turning point in Gesualdo’s life. He was assigned to marry Maria d’Avalos in 1586 in order to fulfill his responsibility as heir. Maria, his first cousin, was twice widowed and significantly older than Gesualdo. Despite bearing a son to the Gesualdo name, she went behind her husband and took part in an affair. Her partner, Fabrizio Carafa, was the Duke of Andria, a man of extreme power and influence.

Gesualdo’s life would never be the same. His anger caused him to set up a trap with other individuals aware of the affair. On October 16th, 1590, he planned to catch his wife and Carafa in bed and conduct a despicable act, one that would go down in history and stain his legacy forever: a double murder.

Despite the atrocious act, Gesualdo was not charged with murder. It was extremely common for Italian noblemen during the late Renaissance period to kill their wives if they prove to be unfaithful. Whether Gesualdo’s act of violence was due to jealousy or due to pure tradition, historians will never know. But what we do know today is that the murder was beyond gruesome, probably causing Gesualdo to spiral into a dark abyss of madness. Interestingly enough, if we listen to a lot of sections of his work, we can see how his mental state made its way into his music.

Rumors spread like wildfire all across Venosa. Gesualdo, his hands dripping with blood, fled the city to his family’s country fortress in order to escape the wrath of Maria and Fabrizio’s families. Claims that Gesualdo was mentally ill damaged his reputation, with some records even falsely suggesting that individuals thought Gesualdo killed Maria’s infant son, Emanuele.

Nevertheless, the double murder was a huge scandal, especially for the upper class in Venosa, quickly becoming a subject for numerous writers and artists. For example, Giambattista Marino, a well known Italian poet born in Naples, loved to reference music of his time into his poetic works. Marino, after hearing the death of Maria, contributed to an anthology of sonnets that mourned her passing.

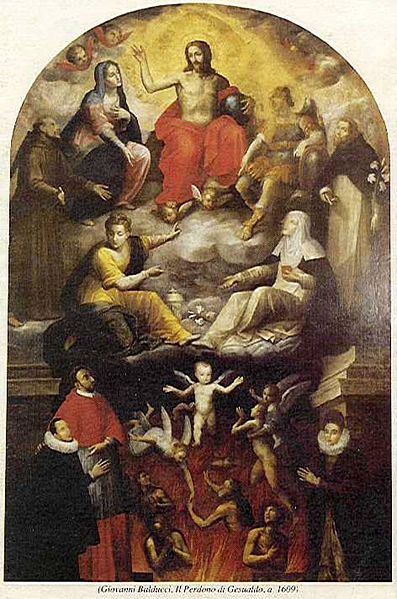

Gesualdo, in an effort to relieve himself of his sins, had commissioned a painting that depicts the murders in a holy light. The painting was meant to atone for his sins and possibly return back on the pedestal of nobility. However, the title of murderer would forever be latched onto Gesualdo like a leech, no matter how far he tried to run.

In 1591, Gesualdo officially acquired the title of the Prince of Venosa, after his father had died, leaving the estate fully under his son’s control. Three years after his ascension as Prince, Gesualdo married his second wife, Eleonora d’Este. Eleonora was the sister of the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso II d’Este, so naturally, the wedding was held in Ferrara.

The marriage caused a huge shift in Gesualdo’s life from darkness, but it was not because of his love life. He was originally very immersed and interested in the music inside the Este Court in Ferrara. Despite going to Ferrara to pick up his new wife, as per the wedding contract, he, in his mind, was traveling there as a composer and a musician.

Gesualdo loved the atmosphere inside Ferrara during his time there and he actually published his first two books of his Madrigals by the Ferrara ducal press in the years 1595 and 1596. As for the marriage itself, Gesualdo did not care for it as much as he did for the music and culture. He left Ferrara without his wife after the wedding ceremony and remained away for seven long months.

Gesualdo eventually returned home to Venosa with his new wife in 1597, and just like that, his life turned to darkness yet again. He was no longer surrounded by the perfect atmosphere experienced in Ferrara, and historians assume that coming back to such a bleak home in Venosa caused Gesualdo’s return to madness. He was horrible to Eleonora and it was reported that he not only cheated on her, but also physically abused her. However, while Gesualdo was mentally unstable at the time, the allegations regarding domestic violence are extremely vague and the documentations are uncredible.

Eleonora disliked her husband with just as much vigor, but never showed any signs of potential affairs. The same cannot be said about Gesualdo. He had two concubines, Aurelia and Polisandra. His intimacies regarding the two women became so severe, extreme, and outright disgusting, to the point where Eleonora accused them both of witchcraft. Some claims were even made that the two were using sorcery and potions to coerce the Prince of Venosa into seduction.

The trial was quick, since the women admitted to being guilty. However, in an effort to protect them from execution, Gesualdo had them imprisoned within his own castle. Afterwards, life in the estate fell back into a bleak shadow. Gesualdo’s only solace in life was composing music. In 1611, he published his last two books of the madrigals. Then, just two years later on September 8th, 1613, Gesualdo died.

His fifth and sixth books were especially unique due to their composition and style as well as how late they were published. Although Gesualdo personally claimed that the final books were composed during the 1590’s, similar to the publications of his other Madrigals, it is known that his final works and their styles become even more pronounced when analyzed against the shifts in musical aesthetics during the late 16th century. His final works crossed the bridge from the Renaissance period into the emerging Baroque period.

The Renaissance period, characterized by its predilection for vocal and choral music, reveled in polyphonic textures and modal harmonies. Meanwhile, the emergence of Baroque era music embraced tonal music, which was music that relied on major and minor scales in contrast to traditional modes. Since Gesualdo was transitioning from both periods, his final works serve as a synthesis of the two styles. He still maintains the polyphonic richness exhibited in the Renaissance era, but also subtly incorporates tonal elements that give his music an eerie, yet dramatic vision. His brilliance in composition and stylistic amalgamation positions Gesualdo as one of the most influential composers of his time.

Gesualdo’s style was classified by some scholars as “Mannerism.” This was a relatively smaller stylistic art movement just before the Baroque era replaced it. Originating primarily in Northern Italy and confined within small parameters of the aristocratic court, Mannerism represented moving from classicism found in the Renaissance behind and focusing more on exaggerated and complex depictions of art. It was the emotional and dramatic segue that soon developed into the Baroque period.

Landon K. Cina, a composer for contemporary classical music, discussed Carlo Gesualdo’s unique style for his sixth madrigal in extensive detail in her paper, ‘Gesualdo’s Late Madrigal Style: Renaissance or Baroque?’ She analyzed different composers, such as Marenzio and Luzzaschi, and their pieces while comparing them to Gesualdo’s own work at the end. “This is not altogether surprising, as Gesualdo spent several years in Ferrara, where Luzzaschi himself called home,” Cina wrote. “Therefore, it is reasonable to assert that Gesualdo’s style can be classified as Mannerism.”

The expressive intensity and emotional depth of Gesualdo’s madrigals can also be characterized by Chromaticism, a music technique that intersperses the first diatonic chords with other pitches. “Carlo Gesualdo’s fame is primarily derived from his use of extreme chromaticism,” Cina wrote. “No. 17 from his sixth book of madrigals, ‘Moro, lasso, al mio duolo,’ 26 has deservedly drawn much attention from scholars because it represents Gesualdo’s most intensely chromatic style.” The deliberate use and incorporation of chromaticism emphasizes Gesualdo’s avant-garde sensibilities.

Gesualdo’s style has undoubtedly played one of the most pivotal roles in shaping western classical music for years to come. He has fused two of the most influential musical eras in history, challenging composers of his time to express themselves in more distinctive and emotional ways. It is no surprise that Gesualdo inspired many other composers. For example, famous Russian composer Igor Stravinsky’s Monumentum pro Gesualdo was written in honor of Gesualdo and his 400th birth anniversary. Stravinsky rearranged three of the madrigals in order to complement his piece, Tres Sacrae Canitones.

Similarly, Peter Maxwell-Davies, who died in 2016, composed Tenebrae Super Gesualdo, which tries to encapsulate the eerie sounds reminiscent of Gesualdo’s own unconventional style from centuries ago. Brett Dean, a modern Australian composer and conductor, was commissioned to compose Carlo, in reference to Carlo Gesualdo, by the Australian Chamber Orchestra. Carlo resembles the intense, suspenseful, and complicated nature of Gesualdo’s sections of the madrigals, and Dean incorporated elements and echoes that would emphasize Gesualdo’s infamous murder.

It is interesting to note that most of the inspired composers categorized their works as “finishing off” what Gesualdo started. Gesualdo died transitioning into a new era, but without addressing how tonality as a style was going to end and what it was going to be replaced with.

Glenn Watkins 1927-2021), who was a professor and specialist of Renaissance forms of art as well as 20th century music, published The Gesualdo Hex: Music, Myth, and Memory in 2010. His book was significant, in the sense that it provided an intricate explanation about Gesualdo’s life and how it weaved into most of his works. His book goes into vivid detail about the murder, the trial, as well as Gesualdo’s mental health as a whole, taking the history of an infamous composer to turn into a vivid tale of mystery and legacy.

Watkins also delved into the style of Gesualdo and how he allowed modern musicians to incorporate their own elements to add onto what he started. Watkins wrote, “What better than for modern music to pick up where Gesualdo had left off? The modernists could thereby claim a lineage and even historical inevitability, while being left free to do whatever they wanted.”

Just as many scholars, such as Cina and Watkins, have observed, Gesualdo’s works tell stories about the most powerful emotions such as love, ecstasy, death, pain, and agony. It isn’t hard to notice how these emotions can be used to understand Gesualdo’s own complex life. Gesualdo made huge strides in the evolution of music, and he has managed to transverse time itself and make an impact in the modern composition of classical music today. However, as much as he was a musical genius, his legacy as a brutal and unstable killer will be forever tied down to his name, no matter how awe-striking his music was in its time and is today.

To listen to Gesualdo’s sixth book of his madrigals, click HERE.

Gesualdo’s style has undoubtedly played one of the most pivotal roles in shaping western classical music for years to come. He has fused two of the most influential musical eras in history, challenging composers of his time to express themselves in more distinctive and emotional ways.