New York City is filled with its fair share of cultural touchstones. There is the pizza, the taxi cabs, and a myriad of tourist destinations, for starters. What else?

“The rats are absolutely going to hate this announcement,” claimed New York City’s sanitation commissioner Jessica Tisch during a news conference, “but the rats don’t run this city, we do.”

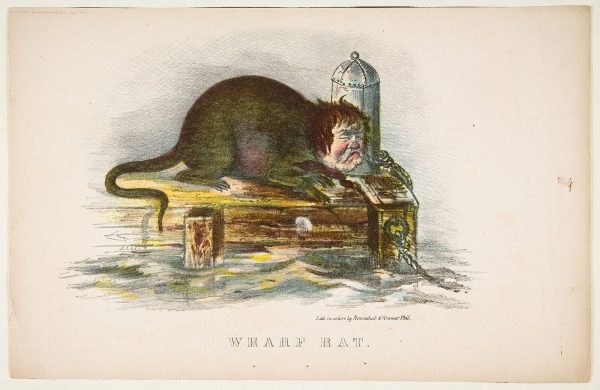

Indeed, one infamous hallmark of New York is the rat.

You find yourself underground in a subway station, ready to go home after a long day. Standing on the platform, your headphones are on when something small and brown scurries just past your feet. If you’re in luck, it may have been New York City’s infamous nocturnal creature, the rat.

The reach of the rat stretches through generations of New Yorkers, hundreds and millions of people. Some people view them with stark disdain.

“It sometimes seems that only deep hatred of the human race could cause the rat to be so destructive,” wrote the legendary New Yorker journalist Joseph Mitchell in ‘Thirty-Two Rats From Casablanca,’ published in 1944, and a classic essay on the subject.

However, not everybody sees rats as pests.

“To me, they’re not much of a hindrance. They’re definitely around and present [in New York], and they have been for a long time, but they also just exist,” said Amanda Gao ’25.

What we know of these creatures is their primary goal of survival. “What do rats need? What does everything on this planet need? It needs food, it needs water, it needs shelter,” said Bethany Brookshire, science journalist and author of Pests– How Humans Create Animal Villains. However common, the sewer rats that proliferate in the streets are a still mystery to society. “We actually know more about polar bears than we do about rats,” added Brookshire.

Amid the divide and its enigmatic identity, how did the phenomenon around rats come to be?

The Arrival

New York primarily sees the likes of the Norway rat — commonly known as the brown rat — today, but they were not always the most populous species of rat. “They only really started spreading, we think, around 4,000 years ago, whereas the original black rat started spreading around 8,000 years ago, so the brown rat is kind of like a new arrival, relatively speaking,” said Brookshire.

In America, the brown rat’s journey started when its modern history did, beginning in the 18th century with the British, the French, and the Spanish. As colonists set sail to the Americas, rats, allured by the food on departing ships, hitched rides to the other side of the globe. Seemingly, the age of conquest in the 17th and 18th centuries may not only apply to humankind. “We can look at their history as kind of a proxy for human history, because humans moved them around the world,” said Dr. Munshi-South in an interview with NPR. Rats, then, also became globetrotters of the New World.

The Outbreak

As America built up its edifices and landmarks, the rats continued to find their way in. From forming networks underground to scavenging remnants of food above them, the rats wove their way into the daily lives of Americans, especially in New York City. Why? The city was and continues to be an epicenter for food waste, the perfect fuel for rats to feed on; thus, the rats spread.

“RATS AT BELLEVUE HOSPITAL. THE CASE OF THE NEW-BORN CHILD GNAWED BY VERMIN — INVESTIGATION BY THE COMMISSIONERS OF PUBLIC CHARITIES — HOW THE HOSPITAL IS OVERRUN,” reads a headline from The New York Times on April 27th, 1860. This rat attack of the Spring of 1860 hit the papers and spread like wildfire.

“This sounds like fiction, but we are assured that it is true,” wrote the anonymous writer, “Myriads swarm at the water side after nightfall, crawl through the sewers and enter the houses.”

Even in the 19th century, rats consistently made their presence known. “All rats are vandals, but the brown is the most ruthless,” wrote Joseph Mitchell. “It destroys far more than it actually consumes. Instead of completely eating a few potatoes, it takes a bite or two out of dozens.” As rats marked their paths, so did their impact on people. In recent history, these invasive populations have continued to rise. In 2018, there were 30,874 cases of ‘rat signs’ — which includes sightings and droppings — at various New York City properties. This total was nearly double that of 2014.

Not only this, but what’s missing from these accounts is the primary concern to many: disease. Rats are social creatures and explorers of the world, but also pathogen-carriers.

Historically, brown and black rats have been linked to the spread of the Bubonic Plague. The ‘Wyoming Affair’ in 1943 scared the country. In 2017, a bacterial infection spread by rat urine killed a Bronx resident. As long as rats traverse the streets, diseases from Escherichia coli (E. coli) to Salmonella continue to spread.

Still, it’s worth noting the general inactivity of these creatures. Have you ever had a friend who has lived in the same city their whole life? What about the same neighborhood? A finding from 2017 by Matthew Combs signals that rats, like some humans, do not travel so far from what’s familiar.

It’s ‘uptown rats’ vs. downtown rats.’ Over time, through generations of rat populations, rats like to stick to their neighborhoods.

“Rats are homebodies. People think that rats can go really far and they can… But just because you can run a marathon doesn’t mean you want to,” said Brookshire. “The average rat really doesn’t tend to venture more than about a block or half a block from where it has been, from where it was born.”

The public health scares that rats generate through their existence in New York City continue to appear in the daily scenes of the city. However, the reputation of the brown rat goes beyond its real-life presence, seeping into recognizable social symbols in literature and culture.

In the graphic novel Maus — a story centering around an interview with a Holocaust survivor — the Jews are depicted as mice and the other ethnic groups as cats and pigs. “That is in part because in the Holocaust, the Nazis depicted Jews as rats, and it was part of the dehumanization campaign against Jews,” said Brookshire.

Rats as a symbol, in many ways, perpetuate racism and xenophobia for those met with a rat-centered insult. While on a surface level, people may squirm at the physical existence of rats, the history of rats as a fuel for hate extends beyond a casual sighting on the subway. “[Jews] are far from the only group… if you’ve immigrated and you’re not British, they’ve called you this,” said Brookshire.

Rats’ mere abundance branches to other variables in society and perpetuates a social stigma — not just on the rats but the people of the city. There is a notion that sanitation and rats often go hand in hand. When there are dirty streets, rats are sure to be there. While this is true on a scientific level, socially, this perception has created a myriad of problems: specifically, classist and racist ones.

Rats are often perceived as an individual problem — “[People think] if you have rats, it’s because your house is dirty,” noted Brookshire — but this a mere misconception. The reason for the rat problem is not up to individual communities, it’s up to a systemic lack of proper sanitation. Why is this distinction important?

For one, a problem ensues when society starts to associate rats with the behaviors of unhoused people. Perception can often outweigh reality. When it comes to rats and people, there is a common perception of dirty rats associated with ‘dirty’ people.

Nowadays, however, “middle class, upper-middle-class rich people, they are seeing more rats and now they’re bothered,” said Brookshire. This uptick in sightings by the wealthier continues to underscore the previous disregard for proper intervention when the rat issue only impacted vulnerable communities. So, what’s changed about the rat war? New York is getting wealthier, New York is getting more rats, and New York thinks rats should be in fewer places than they are.

“But rats have always been there, and the rats have always been a problem for people who were too underserved to do anything about it,” said Brookshire. “That means also that rich people associate rats with filth and with disease and with unhoused people — who often suffer already from huge amounts of stigma.”

Secondly, rats impact the economically underprivileged. With these communities, “Rats are next door. Or down the street. And they can’t do anything about that. And the trash truck isn’t coming… There’s plenty of trash, so there’s lots of rats, and they get blamed for those rats when in fact, what this really is: a societal failure to take care of people who need it,” said Brookshire. While these communities often get blamed for the rat problem, they are the ones most often negatively affected by it.

Why is sanitation specifically necessary then? It can be traced back to the rat’s survival necessities, its fuel for growth: food, water, and shelter. What better source than the high human-to-space ratio in New York City?

Despite these stigmas, street artist Banksy takes an unconventional outlook on the symbol of the rat, making it a subject of fascination and a vector for activism. Bansky sees the rat image — considered to be one of a dirty pest for most of the world — and transforms it under a new, appreciative light. Banksy gives the ‘rats of society’ — oppressed by capitalism and stuck in endless competition — a voice against the system through his art. “They exist without permission,” said Banksy in Wall and Piece, “They are hated, hunted, and persecuted…They live in quiet desperation amongst the filth. And yet they are capable of bringing entire civilizations to their knees.”

The War Continued

Mayor Giuliani. Mayor De Blasio. Mayor Adams. Despite their differing mayoral approaches over the years of their administrations, our three most recent New York City mayors’ common trait is a collective ‘war on rats,’ an attempt to vanquish the rat population from the city’s streets.

Rats, for centuries, have gone where humans go. Today’s age is the same. Where humans drop their trash without regulation is where rats congregate. “The collective solution to rat problems is the management of infrastructure,” said Brookshire, “It’s management of sanitation.”

The effectiveness of management methods has varied. Rat poison, for instance, does not aim to fix the sanitation issue at all. “Have you ever walked across a sewer grate and seen a little piece of wire wrapped around the sewer grate? Yes, that was used to hang a block of rat poison,” said Brookshire.

Current mayor Eric Adams especially seems to have cracked down on rat prevention: “Everyone that knows me, they know one thing: I hate rats,” Mayor Adams said in a past press conference. Yes, it appears that the ‘war on rats’ is still in full throttle.

However, despite the ongoing battle, the new approach has changed. Former elementary school teacher Kathleen Corradi — New York City’s official rat czar — has set a mission to battle the rat population. How? “Rats are a symptom of systemic issues, including sanitation, health, housing, and economic justice,” said Corradi. “New York may be famous for the Pizza Rat, but rats and the conditions that help them thrive will no longer be tolerated.”

A common New York City scene is one with dozens of trash bags on the streets. While these bags may be a nuisance for New Yorkers, it’s a buffet for rats of the night to tear into. What are the possible solutions, then? One way is to improve trash collection. How? Simply, get rid of the big, black trash bags.

“All you really need is a big metal trash can with a lid… think dumpsters, but really secure,” said Brookshire. Currently, the city is beginning to implement this process, formally known as trash containerization — not necessarily eliminating trash itself, but just shielding it from the reach of rats.

Other cities have already had successful containerization efforts. For instance, the Netherlands has underground storage with weekly trash pickups.

Easy, right? Well, it may not be that simple. The big problem is money.

“It’s expensive… Nobody likes that. It takes up a parallel parking space, one parallel parking space or two per block,” said Brookshire. This system would both be costly to implement and would remove up to ten percent of available parking space, a major source of pushback in certain areas.

Despite the potential upset, efforts like containerization seem to be a necessity to actually reverse the problem. “People get mad. It’s that, or when you use that parallel parking space, the rat is going to come into the engine block of your car, and it’s going to chew your wires inside your car engine,” said Brookshire. “Decide what you really want… you manage the trash, you manage the rat.”

The Future

So what’s the consensus? Curious creatures often elicit equally curious reactions from the general public.

“We’ve had rats the size of Crocs… like a Croc shoe? An average size 8,” said Ruth McDaniels, a New York City resident in a viral video clip to CBS News.

“Personally, I like a ferret about as much as I like a rat,” wrote Joseph Mitchell.

“I’m disgusted for a second if I see one… then I move on,” said Amy Li ’25.

“I was at a golf course… waiting to go out. All of a sudden a giant rat came scurrying through,” said Victoria Lu ’25. “It was the scariest thing I’ve ever seen.”

The sensation of the brown rat continues to evolve in the New York City landscape. As recently as October 20th, 2023, the popular subway tracking app, Transit, released its ‘Rat Detector’ website.

Some of the city loathes these critters’ mere presence, finding danger and dirtiness at every corner rats inhabit. Nonetheless, their continued existence remains an integral part of New York City culture for that very reason. While the infrastructure modernizes and the generations pass by, rats have been here for centuries — roaming around at night, and traveling in packs.

Are they public enemy number one? Are they pests that need human intervention? Or, are the humans the ones to blame? Are rats just trying to survive? The answer to all these questions — it’s complicated. Although people’s sentiment towards rats varies, in many ways brown rats serve as New York’s very own mystery.

Regardless, they have certainly been a present figure in the daily lives of New Yorkers, an enigma for the New York population to ponder and experience. What can be concluded about them? Rats will, for better or worse, most likely keep their ‘permanent resident’ status for the foreseeable future, without effective intervention by the city and its residents.

So, the next time that you are walking on the street, maybe question those heaps of big black trash bags. Stop the spread. Clean up your trash. Still, be kind to these so-called pests, because, in this city, everyone is trying to survive. Including the rats.

“What do rats need? What does everything on this planet need? It needs food, it needs water, it needs shelter,” said Bethany Brookshire, science journalist and author of Pests– How Humans Create Animal Villains.