Looking ‘Camp’ Right in the Eye: An Exploration of the Eccentric Aesthetic

Over time, the Camp aesthetic of outlandish over-exaggeration has transcended typical notions of art. From its origins in underground queer communities into the world of modern-day internet culture, Camp has no bounds.

What is Camp?

No, not the one with tents and sleeping bags. Merriam-Webster defines Camp as “something so outrageously artificial, affected, inappropriate, or out-of-date as to be considered amusing.”

You may have never heard of it. If you have heard of Camp, you may associate it with the fashion world or as the theme of the 2019 Met Gala. Or, you may hear the word circle around in the vocabulary of those around you.

Still, what really is Camp?

Known as an art form that embraces flamboyance, Camp seeks an audience. It’s taken a firm place in the likes of fashion and design but is a style that could manifest in any form.

“Camp’s the full expression of one’s self — that’s where the frivolity comes from,” said costume designer Emily Barker, “It’s someone choosing to fully embrace all of the wild, beautiful, and messy parts of themselves and express that all at once.”

Early Origins

Camp has no known beginning, but many agree that playwright Oscar Wilde greatly influenced the aesthetic’s inception. Camp arose from and is intrinsically linked with the queer community and queer culture. Wilde — well-known for his satirical wit and charm — was an early presence in this culture. Aligned with this, what truly made him “Camp” was his affinity for artifice. Take this epigram from Wilde: “The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible. What the second duty is, no one has yet discovered.” His life and work, such as The Importance of Being Earnest or An Ideal Husband, helped create the art of an unserious aesthetic for centuries to come.

In essence, Camp welcomes the phrases “too much” and “overly fantastic,” stripping away the negativity of eccentrics. As Bronx Science English teacher Mr. Licardo describes it, “Camp is being able to look back on something intended to be beautiful, but we think to be too theatrical.”

Notes on ‘Camp’

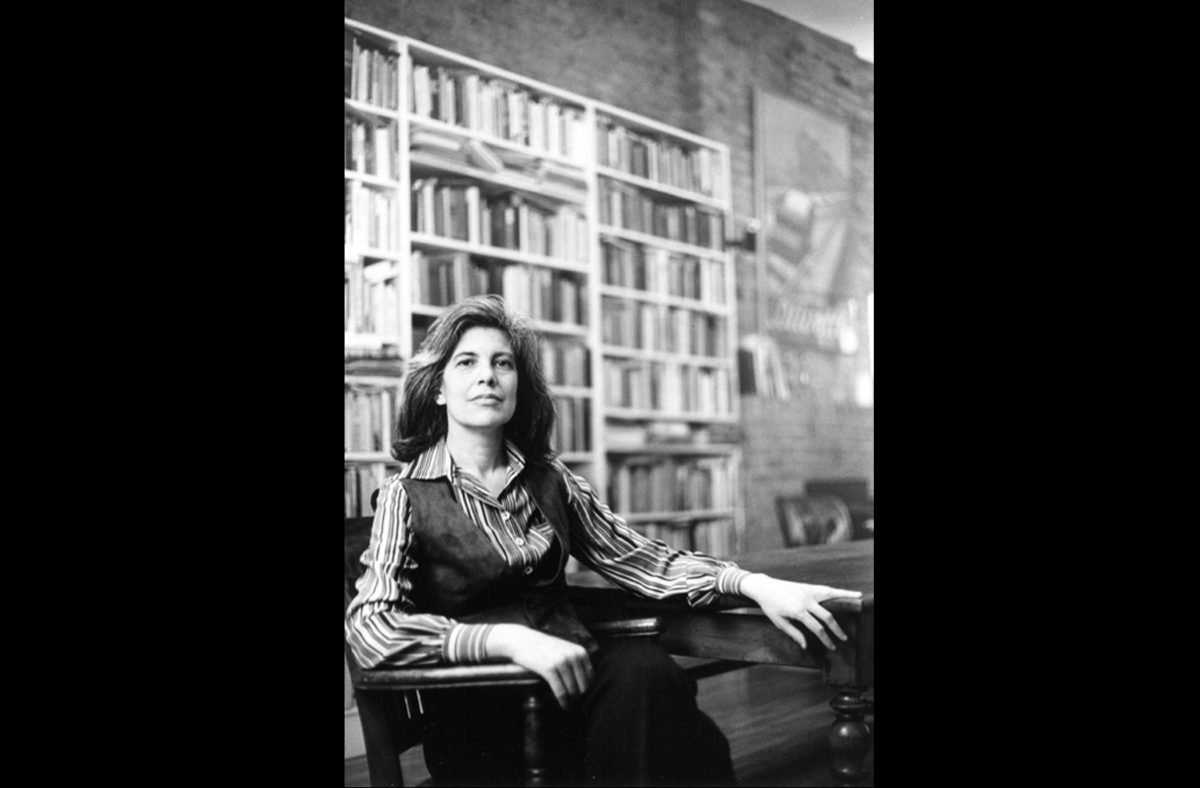

Take these three things: “A woman walking in a dress made of three million feathers.” “Tiffany lamps.” “Swan Lake.” While very different in substance, all of these are attributed to Camp in writer Susan Sontag’s essay ‘Notes on ‘Camp.’ With this single publication in 1964, Sontag helped guide Camp into the public eye. Her piece delved into exploring the spectacle of Camp — to her, true “campiness” lay in the attempt of extravagance. She ventured into the world of exaggerated aesthetics, irony, and theatricality, showcasing how Camp challenges traditional notions of taste and beauty.

Sontag emphasized the sensibility of Camp, a quality of the aesthetic still largely present today. “When I think of Camp, I think of how there’s no specific way to define it, but when executed properly, it’s actually a really fun and creative means of expression,” said Dara King ’25.

Sontag’s influence is undoubtedly profound, but the legacy of Camp still extends beyond her reach. With the exception of a few lines, Sontag largely excluded the queer influence on Camp.

The Queer Subcontext of Camp

From the drag balls of the Harlem Renaissance to fierce voguing dance battles in the 1980s, Camp has always found a place within the queer community. The subversive wit, exaggerated fashion, and theatrical performances of queer entertainers breathed life into Camp, creating a space for the culture to flourish. However, there was (and still is) a struggle behind the excitement. In Barker’s paper entitled, “From Marginal To Mainstream: The Queer History Of Camp Aesthetics & Ethical Analysis Of Camp In High Fashion,” she emphasized this notion: “Most queer folx did not walk around everyday feeling safe or protected enough to reveal their sexuality, so creating a rich hidden nightlife and flamboyant styles was literally a survival mechanism… Camp is an act of defiance from queer people claiming their space and claiming their identity.”

Take Paris is Burning. Made in 1990, the documentary film is a nuanced exploration of the 1980s drag ball culture in New York City — specifically, the documentation of queer Black, Latino, and transgender communities in the culture — and conveys the art of drag in vibrant, yet raw ways. “The documentary parallels some of the codes of Camp by depicting a coded dance and language, showcasing the ball culture’s extravagance and emphasis on style,” said Mr. Licardo, “It foregrounds marginalized communities and sensibilities, similar to the way that Sontag codified camp into a recognizable and definable system of cues and signifiers.” The lively culture represents the thrill of how queerness compels Camp, but the equal focus on the brutality of rebellion offers a powerful statement on the strength of the community as a whole.

Film, Performance, and Camp

Then came the 1970s and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The story follows a recently engaged couple who seeks shelter after their car breaks down; this shelter, however, happens to be the castle of Dr. Frank N. Furter, an alien transvestite from planet Transsexual in the galaxy of Transylvania… disguised as a mad scientist. In the film, Tim Curry puts on a show as Furter, illuminating the screen with androgynous spunk.

In the stage show, the audience participation element adds to the nature of Camp. “Rocky Horror has done a really good job of having this campy, queer space about inviting other people into that… it’s playful and really solidifies Camp as a celebration,” said Barker. With its catchy songs, gender-bending performances, and unabashed expression of sexuality, both the musical and film provide a platform for the exploration of identity and liberation. Still, it offers the element of respect that Camp values. Another text that introduced the world to Camp early on is the 1954 novel The World is the Evening. In this, the protagonist says, “You can’t camp about something you don’t take seriously. You’re not making fun of it, you’re making fun out of it.” Rocky Horror at its core is exactly this: an invitation for fun and an invitation for Camp.

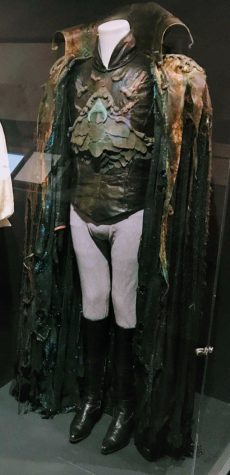

Many pieces of film in this era uplifted a similar spirit. Labyrinth, directed by Muppet creator Jim Henson, brought new energy to the legacy of Camp. As Fiona McLaughlin ’25 said, “It’s got David Bowie — it’s got to be Camp.” Bowie stars as the Goblin King Jareth, while the young Sarah (Jennifer Connelly) attempts to rescue her baby brother in his fantastical maze.

The visual use of puppetry created an awe-inspiring and mildly horrific supporting cast of fantastical creatures, a distinct mark of the absurdities that Camp culture embodies. While many may find Camp difficult to actualize in their day-to-day life, the usage of the aesthetic in film continues to convey the ambitious vision of the style. This extends to every corner of entertainment: for instance, “Barbie is Camp,” said Lara Adamjee ’25.

Camp in the World of Fashion

The subsequent embrace of Camp in fashion continues to largely influence the power of the art form. In particular, the minds of designers Rudi Gernreich and Jeremy Scott elevate this notion.

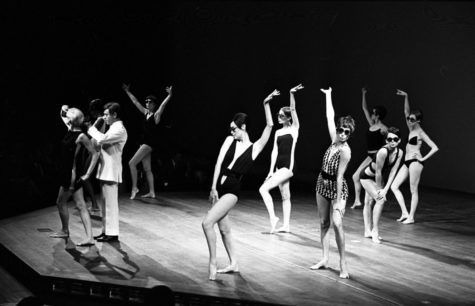

Gernreich helped implement Camp in fashion all the way back in the 1960s. “He was this women’s wear designer that played into this idea of androgyny and subverting gender roles. He created things for women that weren’t necessarily feminine,” said Barker. At the time, he sparked outrage for his embracement of the female figure as an inspiration for aesthetic fluidity rather than over-sexualization. This defiant message was paired with the campy optical effects of the designs themselves: with this, Gernreich masterfully intertwined the rebellion of Camp with its out-of-the-box visual aesthetics.

In 2014, Jeremy Scott’s arrival at Moschino, a high-end fashion brand, came with a bang. Perhaps his most campy look materialized from a satirized image of Chanel, a brand known for its clean elegance. Scott morphed its logo into the golden arches of a McDonald’s logo, typically of a low social standing, and subsequently rejected the conventions of high and low culture.

The look best reflects Scott’s aesthetic and the brand itself: a representation of the social questioning encoded in Camp. As Sontag writes, “One cheats oneself, as a human being, if one has respect only for the style of high culture.”

The Met Gala

To honor Camp, the Met Museum drew inspiration from Sontag’s ‘Notes on ‘Camp’ and created ‘Camp: Notes on Fashion.’ The exhibit explored what Camp has to offer. In tandem with the exhibit itself, the Met also held their well-known “fashion party of the year” in honor of Camp.

Enter: The 2019 Met Gala.

The Met Gala, a benefit for the museum, invites celebrities to participate in the event every year on the first Monday of May. With varying themes from year to year, Camp took centerstage in 2019. Modern fashion designers adorned celebrities with creations of Camp and took them to the carpet.

Moschino, for example, continued its influence: one such notable look was Katy Perry’s chandelier outfit, where she, quite literally, became the chandelier. Taking away the polished glamor of a typical carpet look, Perry displayed Camp at its finest (or lack thereof). Other hits included Lady Gaga and her four outfit changes and Billy Porter’s golden glamor. It can be noted that many successes of the night were worn by queer individuals. Going back to the roots of Camp from Wilde to the early ballroom scene, it’s often queer people who carry out the authenticity and opulence of Camp. Nonetheless, the inherent extravagance of the dazzling night brought Camp out to the world of eager eyes.

Still, the specific notion of Camp at this star-studded event also brought misinterpretations from those who lacked the over-the-top nature of the aesthetic. Some will remember Karlie Kloss’s tweet getting ready for the gala, leading many to eagerly anticipate the potential of her show-stopping outfit reveal.

This, however, was soon revealed on the carpet as a gold dress with puffy sleeves and a mini skirt. The glaring lackluster attempt was and continues to be comical in the eyes of Camp’s supposed overzealousness. At the time, it was a laughable attempt at something that truly contradicted the style of Camp.

But can even this be Camp?

Now, four years later, I say yes. According to Sontag, “Things are campy, not when they become old — but when we become less involved in them and can enjoy, instead of being frustrated by, the failure of the attempt.” Kloss has subsequently, even four years later, become the joke in the midst of her own pitiful attempt. This is Camp. While the dress is not directly Camp, the renewed lighthearted humor of the situation is. While Kloss’s intention was not Camp, the cultural and ironic effects of her appearance are. The true humility of Camp is not often discussed, but to me, it is what solidifies the allure of the style. Above all, Camp is about acceptance. Camp is rarely valued for technical success. Instead, Camp welcomes imperfection and messiness. Camp embraces human nature and enjoys the uniqueness of a character.

The Met Gala had people worldwide googling ‘Camp,’ asking: why? In due time, however, the Internet has too caught on to the fun of Camp.

Modern-day Implications

From a Taylor Swift remix to Wednesday, people have adopted ‘Camp’ into their vocabulary as a descriptor for various aspects of pop culture. This embracement, however, is not always positive. Unlike past interactions of the style, in many ways, the modern parallels to Camp further strip away the depth of Camp and replace it with the casual culture of today’s time. “You see something that’s minorly off-putting and you’re like, oh, it’s Camp, whatever,” said Barker, “But what does that mean, really? [Camp’s] not just something ugly. It’s not just something that’s weird.” Therefore, has this wider spread adaptation defied the core of Camp?

It’s important to note the complexities of the situation. “It’s a double-edged sword,” noted Barker, “It’s important to reach mainstream audiences and share the art and culture. But, a lot of the nuances and depth can be lost with Camp.” Is the mainstream embracement of Camp a current sign of capitalism’s corruption of the art form? “Camp is the answer to the problem: how to be a dandy in the age of mass culture,” writes Sontag. Both these notions are challenged by perpetrators of current Camp.

Take the Met exhibit: with a large exposure by such high-prestige people attempting to revitalize Camp, the Gala associates itself as a celebrity epicenter for photographs and an appeal to the masses. In some ways, this commercialization and inherent “high class” facilitation of Camp waters the aesthetic down: decades of culture are being reduced into the hands of the (typically white) elite for profit.

In even more recent events, one must also consider the social and political climate of Camp — why is the aesthetic itself seen as a celebration, while queer origins of Camp are violated? Rampant drag bans and gender-affirming healthcare violations in politics today erase the voices of Camp. “Today, we still do see a lot of this institutional homophobia,” commented Barker in her paper, “There is a certain type of cruelty in majority culture picking and choosing which facets of queerness one wants to consume.” This especially reigns true against BIPOC communities — Camp is not an exception to white appropriation and extreme discrimination.

In a changing world, the respect and honor of Camp remain paramount to keep evolving and reaching others today.

“Camp is people saying we want to be different, and we want to be remembered,” said Judah Bulow ’25.

“Being super serious all the time is just not fun. Embracing this, Camp still makes itself a standout art form,” said McLaughlin ’25.

“It’s the freedom, and it’s the liberation that makes Camp alluring to me. It’s seeing people be so vibrant and take up space that is inspiring to see: it’s a celebration of life and identity,” said Barker.

Camp is disorder. Camp is ‘too much.’ Camp is unlimited. Camp is anything but boring. Camp is anything but ordinary. Camp is everywhere we look. While a definition conveys this at face value, the heart of understanding true Camp lies in the active creation of the style. It lies in the people who choose to keep it alive and keep it authentic. So now, I say — keep Camp thriving.

“Camp’s the full expression of one’s self — that’s where the frivolity comes from,” said costume designer Emily Barker, “It’s someone choosing to fully embrace all of the wild, beautiful, and messy parts of themselves and express that all at once.”

Tammy Lam is an Arts & Entertainment Editor for ‘The Science Survey.’ She believes that journalistic writing is important for enabling truths that...