The Transcendent Beauty of Chinese Ink Paintings

Chinese ink paintings are an exquisite fusion of art, language, and philosophy, capturing the essence of subjects and evoking a sense of tranquility and profound contemplation.

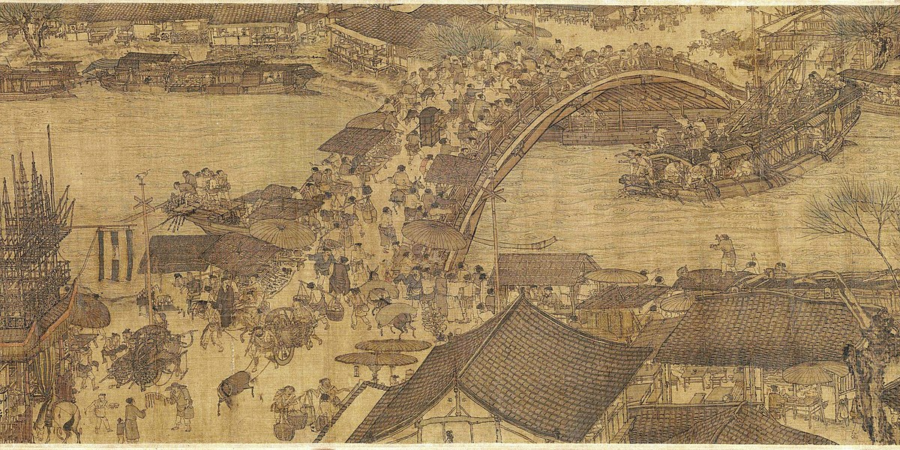

This is a portion of ‘Along the River During the Qingming Festival’ by Northern Song Dynasty painter Zhang Zeduan. It is dubbed “China’s Mona Lisa” due to its level of recognizability. The piece captures the lively atmosphere of the Qingming Festival rather than the ceremonial activities like tomb sweepings. The original work is 207 inches in width and captures a wide variety of people across the town. (Photo Credit: Zhang Zeduan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

My first encounter with Chinese-style ink paintings ironically does not stem from having visited China, nor is it from my exposure to an authentic work of traditional art. Instead, it is the opening title sequence of Disney’s 1998 Mulan. The unassuming prelude possesses an enchanting allure: the screen is at first a wheat-beige color, mimicking the hue and crinkled texture of ancient parchment. Then, a droplet of black cascades across the page; the bleeding ink takes on a life of its own, dancing across the surface as if guided by invisible hands. It weaves and swirls. Two strokes merge into one stream. Mountains rise, their majestic peaks reaching towards the heavens while the wispy clouds embrace each other with their washed-out appearance. A vibrant monochrome tapestry is woven before our eyes. The free-flowing strokes embody the same spirit as the masters of ancient China even though the Disney imitation pales in comparison to the originals.

The Master’s Tools

To get a taste of Chinese ink paintings, look no further than the tools themselves. The artisan needs only a few instruments — a brush, an ink stick, an inkstone, and special paper or silk — to turn their imaginative visions into a tangible form. Before even touching the brush to the canvas, the artist engages in the meditative process of grinding the ink stick, transforming it into a luscious paste that will breathe life into every stroke and become the very essence of the work.

While the word “grind” may conjure up images of applying immense pressure, the process of preparing the ink stick for these paintings is a delicate and nuanced affair. Rather than exerting excessive force, painters allow the stick’s natural weight to guide their movements effortlessly. After a few droplets of water are added to the inkstone, the hardy block of dried pine soot leaves behind a trail of rich dark puddles, creating wells of possibilities.

The mortar-and-pestle exercise is meant to be a contemplative one. The painter is fully absorbed in the task at hand. The rhythmic circling motion settles their mind and prepares them to create. The black pools shimmer at the surface of the glossy inkstone in anticipation of the brush and the hearty strokes to follow.

A Bit of History: Understanding the Soul of Literati Paintings

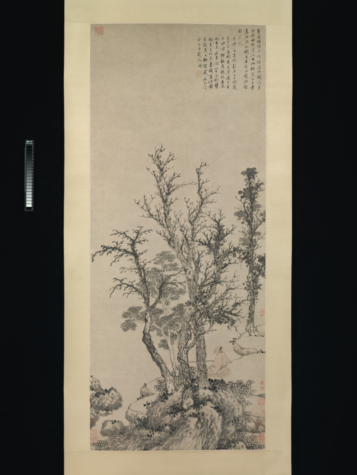

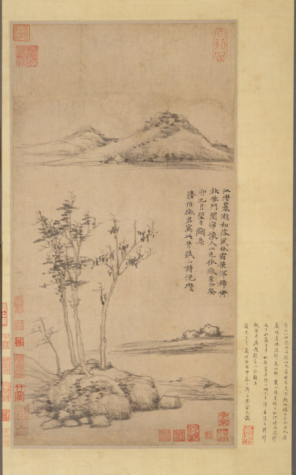

During the Tang Dynasty, a new style of painting known as “literati paintings” emerged, surpassing the earlier gong-bi court style in popularity. While gong-bi paintings employed precise brushstrokes to depict colorful historical narratives or figures, literati paintings, also known as shui-mo or freehand style, embraced a monochromatic palette. They prioritized the expression of spirit and essence over strict accuracy, as evidenced by the bold and untamed brushstrokes.

One of the prominent figures during the Song era, Su Shi, a highly esteemed scholar and statesman, is often regarded as a representative of the literati painting theory. He expounded on the two fundamental concepts within shui-mo: changxing (constant form) and changli (constant principle). The former includes humans, animals, buildings, and man-made objects, wherein anything that can be reproduced adheres to a consistent form.

While humans and animals are not clones of one another, they do follow a fundamental blueprint. Kong Lingwei, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Art, explains that there are limits to how many eyes, limbs, and heads we can have before distorting into fantastical creatures. When drawing people, the leeway for experimentation is small.

On the flip side, constant principles manifest within natural elements such as bodies of water, mountains, clouds, trees, and grass. Nature lacks rigid and fixed forms. Smoke continuously rises, waves intermingle, trees sway and grow new limbs every day, and the mountain’s ridges are infinite. These systems follow constant principles instead, as they are governed by the dynamics of water, wind, and air which obey the physics of our universe.

East Meets West

It goes without saying that the paintings of China and Europe during this time period exhibited distinct differences. Western art pieces often utilized an oil base, which provided artists with the flexibility to make corrections and revisions, essentially allowing them to draw on top of their mistakes. In contrast, when a Chinese painter makes an error, it becomes an integral part of the artwork, as it is etched into the very fabric of the art itself.

The two cultures also had contrasting philosophies towards self-expression, especially among the literati and European artists who primarily drew religious works. An encyclopedia entry for East Asian Art claims that Western art has “an exhibitionistic spirit […] There is […] the effort to rival nature, to be scientifically right. [For] the Eastern artist […] the copying of natural aspects […] is the least of his undertakings. He studies nature in the large, concentrating his faculties upon understanding the greatest and the smallest of her phenomena, brooding with her. But his pictures are less a report of something seen than a distillation of a mood or a spirit felt. His most potent language is not the detail or outlines of the composition observed, but the intimation that came to him in contemplation.”

In other terms, there is an emphasis on individual expression and scientific accuracy in the West, while the East focuses on capturing the essence of nature and conveying a contemplative, abstract representation of the artist’s inner experience.

Moreover, Western art critics often turn to symbolism to explain the popularity of Chinese ink paintings, but their traditional criteria of art do not easily apply here. Works that offer a technical mastery of anatomy and linear perspective are showered with praise but since these abstract ink paintings offer neither, the critics turn to symbolism to inject meaning into the piece. The paintings are not symbolic though but just an expression of the scholar’s inner world.

Reading Between the Lines

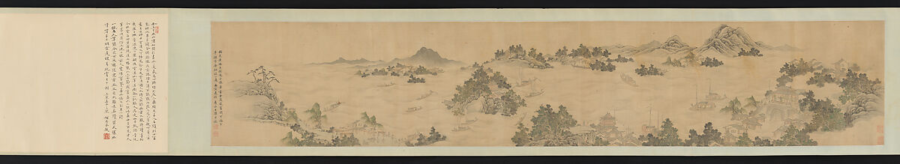

During the pre-Song dynasty era, paintings were often affixed onto walls or pasted onto wooden folding screens. However, two new formats — the Chinese handscroll and the hanging scroll — later emerged due to the resourcefulness of the painters. Silks that were no longer suitable for officials and courtesans to wear but still too beautiful to discard were skillfully transformed into scrollwork. Artists cut the fabric, backed it with paper, and topped the ends with wooden rods for structure. The resulting art form is flexible, lightweight, and mobile, allowing for convenient packing and display.

While Western works are primarily hung on walls for public enjoyment, the continuous display of a scroll ironically detracts from its intended beauty. Chinese handscrolls are bought out on special occasions such as scholar-painter gatherings only during which they are unrolled slowly and viewed one shoulder length at a time.

Unraveling a scroll is an intimate artistic experience and the anticipation of seeing the naked work is akin to unwrapping a mystery gift. Unveiling the bride (scroll) is as involved as opening a Russian Matryoshka nesting doll. After removing the painting from its intricately carved box, the audience must peel back the layer of silk, tied with an ivory or jade clasp. This ceremonial process serves to slow the viewer down but also to reinforce the idea that the artwork is precious, befitting of such protections.

The experience is highly personal and intimate because the person is directly handling the artwork, admiring one section at a time from right to left, before rolling the section up in favor of the next. The individual has an autonomy previously unseen in art; they have the freedom to unravel the scroll at their own pace, relishing some sections while skimming over others. Even from a short distance away, the lines can be hard to discern. Thus, the handscroll can only admit one to two attendees at a time due to the forced proximity.

An Open Book

As it unfurls, the painting tells a narrative story over space and time in both the real and imagined world. Just as one has to move across the length of the scroll to reach its end, the piece’s contents are constantly changing and moving as well. Dawn Delbanco from the Department of Art History and Archaeology compares analyzing a handscroll to reading a book. In fact, the Chinese use “读画 du hua” (to read a painting) to describe the act of viewing an artwork.

The interplay between image and text is a hallmark of Chinese paintings, with poems and colophons accompanying the illustrations, offering insight, commentary, and a historical thread. In a sense, Delbanco is right in his comparison. In the additional sheets of silk or paper that follow the illustration, there are colophons, similar to book reviews, inspecting the quality of the work, contextualizing the time period for later viewers, giving a biographical account of the painter, or responding to earlier colophons.

Moreover, the presence of red seals bearing the names of previous collectors further enhances the scroll’s significance, providing a record of its proud owners and acting as a seal of approval. In this way, the handscroll not only reveals a pictorial representation but also immerses the viewer in a rich dialogue between past and present, art and literature.

These inscriptions written in calligraphy, with their mastery of brush and ink, hold a revered status in Chinese culture as a sophisticated art form in its own right. When combined with scroll painting, it adds an extra layer of meaning and beauty to the artwork.

Often, calligraphic inscriptions, poems, or passages from famous literary works offer visual and textual dialogue. The interplay between the expressive lines and strokes of calligraphy and the brushwork of the painting creates a beautiful synergy, where the written word becomes an artistic element in itself.

For instance, Tao Yuanming’s Xing Zeng Ying (From Body to its Shadows) reads:

“Heaven and earth do not perish;

mountains and rivers do not change;

grass and trees have constant principles;

frost and dew wither and revive them;

people are the most intelligent but hard to compare with nature.”

The poem illuminates the sentiments of the popular landscape paintings at the time: nature is eternal but we are not. Nature’s pulse is consistent even if it withers some days; though we are smart, we are far behind nature because we do not understand the internal rhythm of life.

The MET

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The MET) has an extensive holding of Chinese paintings. The collection was expanded during the 1970s through the contributions of Douglas Dylan, Oscar Tang, and John Crawford. Despite their majesty, these works are fragile to the soft elements of light and time, so no one painting is displayed for long.

Rotations average only six months, but the bright side is that museum-goers always have new works to observe. When I visited the gallery, the theme was “Learning to Paint in Premodern China.” The lighting was dull and warm, yellow as the pages of the scrolls themselves. It was almost as if I were stepping into one when I entered the gallery, moving from painting to painting, similar to how time is portrayed in the scrolls.

I had snuck away from my friends in the Armory room. It was much quieter and emptier in the Chinese paintings section — the visitors stood in quiet contemplation mirroring the ancient masters before them. I stood by Grooms and Horses thinking to myself, I’m looking at something that’s been housed in the Forbidden Palace meant for the pleasure of the Emperor.

An encyclopedia entry for East Asian Art claims that Western art has “an exhibitionistic spirit […] There is […] the effort to rival nature, to be scientifically right. [For] the Eastern artist […] the copying of natural aspects […] is the least of his undertakings. He studies nature in the large, concentrating his faculties upon understanding the greatest and the smallest of her phenomena, brooding with her. But his pictures are less a report of something seen than a distillation of a mood or a spirit felt. His most potent language is not the detail or outlines of the composition observed, but the intimation that came to him in contemplation.”

Nicole Zhou is the Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Observatory' yearbook and a Staff Reporter for 'The Science Survey' newspaper. This is her third year revising...