From a Colonial Outpost to a Revolutionary Symbol: The Evolution of American Identity at the Fraunces Tavern

Learn about the rich history of Fraunces Tavern, one of New York City’s oldest buildings to date and a very popular tourist attraction (with good food!)

This lovely tavern, located on 54 Pearl Street in downtown Manhattan, was once a very active revolutionary pub for patriots during the years of the American Revolution. It’s a wonderful spot to visit if you’re interested in the history of New York. It’s amazing to know that you’re eating in the same spot as our first president.

Sometimes, it’s easy to forget that the bustling city that I’ve lived in for my entire life holds a rich tapestry of historical essence, woven together by years of cultural fabric that stretches back several hundred years. It’s certainly hard to perceive; the glittering skyscrapers, the crowded streets, the stream of tourists all were once non-existent. Yet, there also exists another side of the coin, another side of the road. Although the city itself is growing more and more, filling the skylines with extra splendor, there still exist small roots of the past scattered throughout the Big Apple.

Nestled between towering buildings on 54 Pearl Street in Manhattan, overflowing with character, Fraunces Tavern embodies this idea of woven history. Located at the very heart of the Financial District in lower Manhattan, this iconic building has stood the test of time, bearing witness to a drastic change in city development. Its construction dates back over three hundred years ago, making it one of New York City’s oldest buildings still standing today. The tavern itself is a popular tourist attraction, inviting visitors to experience a unique atmosphere and to enjoy historic charm and delicious cuisine. For city fanatics interested in the cultural heritage of New York City, Fraunces Tavern also serves as a reminder of America’s developing identity and its past.

To understand the context of how Fraunces Tavern first became constructed, let us first delve into the history of pre-colonial New York. The island of Manhattan was first inhabited by the Lenape people, specifically in the lower Hudson River Valley and the Delaware Valley. In fact, Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano encountered the Lenape people in Lower New York bay. Later on, when explorer Henry Hudson made his voyage to what is now New York, discovering the Hudson river, the Dutch empire and the Dutch East India Company were able to make land claims of their own. In 1625, the capital of New Netherlands, New Amsterdam, was created, influencing fur trades with the natives in the region and developing the Dutch economy.

This age of prosperity for New Amsterdam came to a close when Great Britain started to take interest in the land. In 1664, the British organized a takeover, resulting in the colony being granted to the English crown after a two year war. New Amsterdam ultimately became New York when the Treaty of Westminster was signed. The island of Manhattan was soon able to make strides in trade and exports, boosting the colony’s economy through water transportation and ports. Because the city needed a new market house and ferry building, it sold lots in part of the Great Dock along Pearl Street in 1691. This mentioned land is remarkably the same ground where Fraunces Tavern is standing today.

Pearl Street was purchased by Stephanus Van Cortlandt, son of Olaff Stevenson Van Cortlandt, an officer in the set-vice of the West India Company of New Netherlands, in 1686. Stephanus’ daughter in 1700 married Stephen De Lancey, who purchased the land the very same year of his marriage from his step-father. Around 1719, De Lancey applied to the city council for more added land on his property so that he could construct a “large brick house.” It is unknown if the construction project was used as a private residence for De Lancey and his family, but in 1737, Henry Holt rented it. For the next three years, Holt utilized the building to host balls and dance lessons, contributing to colonial society and identity. After all, the balls were a way for colonists to connect with European styles and cultures despite being an entire ocean away from the motherland.

After a brief period of residential purpose, the firm De Lancey Robinson & Co. purchased the building in 1759. In a short period of time, the structure was used for trading purposes, exporting manufactured goods such as Indian textiles, rum, and sugar. This in turn played a major part in New York’s trading development. At the same time, tensions between colonial residents and British soldiers were making their way up into the surface. The recently ended French and Indian War forced Great Britain to become knee deep in debt. To compensate, numerous taxing policies were endowed on the 13 colonies in the following years, angering many.

In 1762, just before the Seven Years War ended, Samuel Fraunces bought 54 Pearl Street from the company. There is very little known about Fraunces and who his character was in early years, unfortunately. But the notable fact was that he was a strong patriot and an amazing cook.

Fraunces opened the tavern, then known as Queen’s Head Tavern, under the sign of Queen Charlotte of Great Britain. The tavern was immensely popular; due to his expertise and the bustling Great Dock, Fraunces had no problem attracting customers. Because of its popularity, the tavern brought in numerous gatherings from many different organizations. For instance, The New York Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1768, right in the heart of the tavern! New York Society Library, founded in 1754, also regularly held meetings at the tavern. Other groups took part in experiencing Fraunces Tavern’s enjoyable atmosphere and charm, such as social clubs and religious affiliated organizations. Merchants and traders also drank heavily here, bringing in relevant events and ideas to the table.

The tavern did not spring its revolutionary associations out of nowhere, however. Among the many organizations that relaxed under the tavern’s roof, so did the famous Sons of Liberty, patriots of the growing revolution. As a result of the boiling tensions of recent tax implementations (such as the Stamp Act and Sugar Act of 1754) many colonists ventured to their favorite taverns to rant. Add in the SOL’s regular meetings and Samuel Fraunces’ patriotic viewpoints, and the tavern was destined to become America’s hub for wartime involvement.

In the year 1775, Fraunces opened the door to the New York Provincial Congress, a temporary legislature for the colony of New York, inside the Long Room. The congress chose delegates and representatives to partake in deep revolutionary activities, such as selecting few to participate in the Second Continental Congress. In the very same year, the Hearts of Oak militia (a group Alexander Hamilton was once part of!) got together at the southern tip of Manhattan and shot a British ship, the MHS Asia. To retaliate against the militia’s efforts, the British shot a cannonball into the city. As a consequence, the roof of Fraunces Tavern was hit, creating a huge hole that was repaired later on.

Ever since, the tavern’s active support for the war, many significant revolutionary figures passed through. It is not so surprising, considering that the tavern was considered a revolutionary headquarters for New York. George Washington was a regular visitor, as well as John Jay, James Dune, and other members of the provincial congress. The tavern held secret meetings primarily in the Long Room, since it was (as its name suggests) spacious and reserved for private events.

The tavern continued its role as a reservation for revolutionary affairs after the British surrender at Yorktown. Trials for African Loyalists occurred inside the tavern, overseen by General Birch. The loyalists were able to prove their loyalty to the British crown, and as a result, were granted a safe passage to freedom in England. As negotiations between American colonists and the British continued regarding troop evacuation, the tavern operated as a civic space.

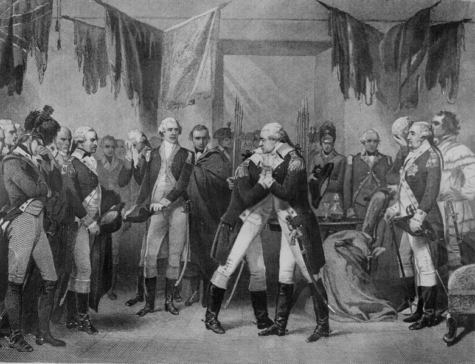

Of course, George Washington’s famous farewell address to the soldiers of the Continental Army happened right in the tavern. On December 4th, 1783, an emotional parting between a general and his faithful, strong, troops who have gone through so much together, closed off a chapter of the newly formed independent nation for good. With a drink of wine and tears dropping down each soldier’s face, Washington bid his goodbye. “With a heart full of love and gratitude, I now take leave of you. I most devoutly wish that your latter days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable.”

In 1785, the Confederation Congress rented out rooms for the Department of Foreign Affairs, led by John Jay. In the same area, the Department of War, led by Henry Knox, and the Board of Treasury, Hamilton’s department, also took up space to discuss political developments of the nation going forward. It wasn’t just revolutionary associations; the tavern was impactful regarding some of the earliest political decisions of the United States.

Three years later, in 1788, the federal government granted the tavern to John Francis. Francis turned the post-revolutionary hub back to a regular old tavern that welcomes customers warmly. The Long Room now became a center for lectures and dances, reinforcing a growing new American identity right at the heart of the New York City harbor. Despite the offer to move the tavern to the new capital at Washington D.C, the tavern continued its success by remaining in the ever growing trade city.

54 Pearl Street as a whole adapted to the drastic changes as time progressed. As more immigrants flocked to the United States for work opportunities, New York City, a major city for industrial development, had to create more spaces for living situations. Even though the tavern itself was changing, having been sold to different owners year by year, its involvement was never buried. Patriots still held gatherings at the tavern, reminiscing about war time and living as freemen, the dream they achieved through hard work. Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr also attended a meeting held at the tavern, led by the Society of Cincinnati. What is the surprising thing about this fact? This meeting was held a week before their famous duel that ended Hamilton’s life.

During the 1830’s, the road added eleven other buildings next to Fraunces Tavern. Around the same time, the tavern itself served as a boarding house, with the first floor reserved for the actual bar. Even though the building was extremely old, it continued to grow as the American population grew; it was a proficient reminder of how the nation expanded its borders, its citizenship, and its identity.

Fraunces Tavern was no exception to destruction, despite its age. The building suffered from numerous deadly fires, causing renovations to take place. It’s no surprise that owners saw the fires as opportunities to adapt the tavern to modern improvements. If America was expanding, so too would Fraunces Tavern. More floors were added with more rooms and space. A flat room also accompanied the additions. By the 1900’s, the building no longer looked like what it used to during the revolution.

With rapid industrialization, space was needed, but it was scarce. Architects took down old buildings and replaced them with larger, taller, and more modern structures. When 54 Pearl Street was threatened to be demolished, the daughters of the revolution, as well as Andrew H. Green (founder/president of the Society for the Preservation of Science and Historic Places), tried to save the tavern from this fate. Due to their efforts, in order to prevent owners from destroying the historic tavern, New York City officials designated the area as a park. Later, in 1904, the tavern owners agreed to sell the property to SRNY (the Sons of the Revolution in the City of New York).

The SRNY truly desired to see the tavern restored to its former glory. Thus, the mission of remodeling the tavern into a restaurant and a museum began. This task at first was daunting; as a result of the devastating fires, there was no recollection of how the property used to look. After years of digging and stripping down the tavern, restorers were able to determine the material originally used, as well as the original slope of the roof. On December 4th, 1907, the building was opened to the public. It was a momentous occasion, for the American people were reminded of Washington’s emotional farewell 124 years earlier.

I had the opportunity to travel to the tavern on May 21st, 2o23. The day was absolutely beautiful, so I asked my mother and my sister to come with me to “experience something new.” My sister, despite having her own homework, agreed. The day was too beautiful to ignore, so we took a nice stroll inside Battery Park alongside the waters. We also went ahead and walked near a restaurant that my father used to work in when he first came to America; it was a luxurious bar and grill that had a great view of the Upper New York Bay. Immediately, I was reminded of the task at hand; Fraunces Tavern was waiting for me after all.

When we stepped inside, I was immediately greeted by welcoming and friendly staff who kindly asked us what we wanted to do. I responded by telling them that we desired someplace to eat. A woman smiled and guided us to a table reserved for three. I loved it. The table was all the way in a corner with a window standing right behind it. Next to the window, so many photo frames were lined up; upon closer inspection, I realized that they were old propaganda posters, sketches of Washington, and certificates.

The seating, as my sister pointed out, was notable. There was a small candle right in the middle of our table, shining brightly against the dimly lighted scenery around us. The tavern was filled with the sounds of live music; when we were settling in, a performer was expertly playing the saxophone. When he finished, the people in the bar clapped loudly. Despite being in the corner, my family had the best view of the dining room. To the right, we saw folks cheerfully drinking and conversing with the bartender. Off to the side, more people were eating or waiting for their food. The window that was right behind me allowed me to see the outdoor seating arrangements of the tavern as well as the bustling streets right across. I was able to relax and stare outside, while also listening to the traditional folk music that was playing.

Our waiter was a young woman with a very prominent smile. She was efficient in bringing us menus and glasses of ice water. When we told her we were ready to order as soon as she came over, she laughed. “That was fast. You guys came prepared!” I smiled, explaining that I was here to write an article about the tavern for The Science Survey. She opened her mouth, forming an ‘oh’ in understanding. “That’s so cool! There’s a lot of history surrounding this place.”

She was exceptionally kind. Since she knew I was doing research on this place, she gave me a little piece of paper that explained the historical significance of the tavern. I also asked more about the frames sitting behind me, and she gave me context for quite a few. One of them was a confirmation letter that was sent to the New York Council regarding the demolition of the tavern back in the 1900s. Another was a portrait of George Washington made after his presidency. “We have many more in the museum,” our waiter reminded me. “Make sure to come again before it closes.” I nodded, embarrassed that my family and I arrived exactly when the museum closed.

We didn’t wait a long time for our food, which surprised my mother. She usually loves to complain about how long American restaurants take to cook and to serve food that has been ordered. We ordered vegetarian dishes due to our dietary restrictions; I helped my mother out by explaining what each dish consisted of. We were soon presented with an Asian stir fry, some flatbread topped with cheese and vegetables, some regular mac and cheese, and some garlic fries. Of course, my sister, who has a huge sweet tooth, ordered a warm chocolate chip brownie for dessert, which came in after our meal. The food itself was great. My mother, who rarely ever eats anything outside our South Asian palette, couldn’t help but express her delight regarding the Asian stir fry. She also loved the mac and cheese.

My sister and I asked some more questions to our waiter. Despite being so knowledgeable about the history of the tavern, she had only started working as a waitress for about a month or so. She also revealed to us that she is a live performer – a singer to be exact, for the piano bar upstairs. “How long have you been singing and playing the piano?” I asked. “Seven years!” she proudly answered.

After finishing, we were presented with the bill; it was a fair amount of money. After paying, our waitress bid us farewell. “Good luck on your writing!” she said to me, as we walked out. The sun was beginning to set, casting the building with a warm orange glow. For someone who rarely eats at dignified restaurants, I was especially happy to have come here with my family. It’s truly spectacular how a normal looking building could stand out amongst other structures, while still retaining a firm grip of American idealism.

We as a nation are always changing, always developing, and always pursuing. The Fraunces Tavern itself is no different. Its past identity as a Colonial hotspot for revolutionaries is framed on a wall, always to be remembered. But in the present, it is now a popular tourist destination with numerous individuals coming to enjoy themselves.

Can something be stuck in the past but also move alongside the future? I asked myself this question, as I was walking back home with my mother and sister. In the distance, across Battery Park, stood skyscrapers tall and proud, merging in with the sea of clouds above. Even farther, I could make out the small silhouette of the Statue of Liberty. Of course, things can represent both past and present: Fraunces Tavern is one of many historic treasures that embody change and also embrace the past.

To learn more about visiting the tavern, you can find information at their website frauncestavern.com. For information about their museum, you can visit frauncestavernmuseum.org.

The tavern itself is a popular tourist attraction, inviting visitors to experience a unique atmosphere and to enjoy historic charm and delicious cuisine. For city fanatics interested in the cultural heritage of New York City, Fraunces Tavern also serves as a reminder of America’s developing identity and past.

Maliha Chowdhury is an Editor-in-Chief and a Social Media Editor for ‘The Science Survey,’ and she enjoys the value of truth that is expressed in journalistic...