Mango Mania: The History and Culture of Mangoes

The significance of mangoes in South Asian cultures and religions remains momentous, even after 4,000 years.

Mangoes, known as the king of fruits, originated in India over 4,000 years ago. The fruit was introduced to other parts of the world through traders and colonizers, and is now cultivated in most frost-free tropical climates including the Americas, the Caribbean, Spain, East and West Africa, and Australia.

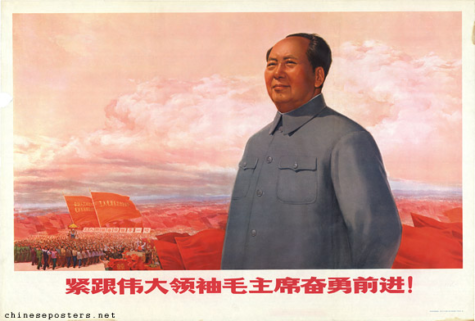

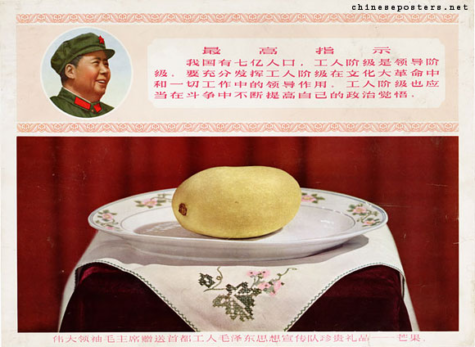

As China was grappling with a mania for mangoes during the Cultural Revolution, Chairman Mao’s Mango Cult swept the nation. In 1968, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Mian Arshad Hussain gifted a box of mangoes to Mao Zedong, the Chinese Communist Party chairman and leader of the People’s Republic of China. Although it was a small gesture — in fact, during mango season in South Asia, seeing people proudly carrying boxes of mangoes as gifts for their loved ones is very common — it had a profound effect on Chinese society.

Around the same time as the reception of the mangoes, after a brutal clash between two rival factions of the Red Guards and Qinghua University, Mao sent in 30,000 workers from Shanghai to act as a buffer between the groups and maintain peace. This plan backfired and dozens died while hundreds were injured. Instead of eating the mangoes, Mao re-gifted them to the workers (supposedly Mao did not like the taste of fruits), sending one mango to each factory.

Mesmerized by this rare foreign fruit that almost nobody in China had seen before, the Chinese appointed the mango as a bearer of magical properties, associated with immortality and eternal life.

Mangoes became sacred throughout China. Workers chose to preserve the gifted mangoes with formaldehyde or wax, and would bow to their factory mango as it served as a symbol of their leader’s devotion to them and the nation. Moreover, mango motifs appeared everywhere — on household items, posters, parade floats, and textiles. Although today you can still buy authentic items with mango motifs on it from that era, the Chinese government discourages selling them to tourists.

So, where do mangoes come from?

“My dad told me that when he and his brother were kids back in India, they would sneak onto their rich neighbor’s front yard because they had mango trees,” recalled Tanushri Sundaram ’22 as we shared stories of the prevalence of mangoes in our lives. “And they would climb mango trees during sunrise and steal mangoes! They would just sit up there and eat mangoes for breakfast.”

Originating in India over 4,000 years ago, mangoes, scientifically known as the Mangifera Indica, are the national fruit of India, Pakistan, and the Philippines, and the mango tree is the national tree of Bangladesh. Mango trees can live for hundreds of years, and they continue to bear fruits even after 200-300 years. Commonly known as “the king of fruits,” mangoes are rich in vitamin A, which is essential for eye health, and vitamin C, essential in forming collagen and improving skin elasticity. Their high acidity has made them a legendary medicinal cure for many ailments from digestive issues to heat strokes to the common cold.

Many people have described a mango’s flavor as a mix of peaches, oranges, and pineapples, and its versatility has inspired hundreds of dishes across cultures. In a mango ceviche, for example, mangoes add a tangy flavor to the distinct Mexican dish which usually consists of avocado, chili powder, and garlic. Mango and Thai basil ice-cream with coconut shavings is a popular mango dessert found across Thailand during mango season. Other dishes include mango habanero hot sauce, tropical slaw, chardonnay mango pecan tart, contemporary coronation chicken, mango salsa, tamarind and mango mud crab, and chargrilled trout with leek and mango salad.

(Part of the Stefan R. Landsberger collection / Chineseposters.net)

“Mangoes are everywhere in Bengali dishes, from achars to spicy hot curries to mango chaat as a refresher on summer days,” said Aniqa Chowdhury ’22, a student at Trinity High School and a practicing chef, when asked about mango dishes in her culture.

“I also love how my mom makes fish mango curry, which is both savory and sweet. But my favorite way to eat them, ever since I was a kid, is whole, peeling off the skin and taking bites out of the juicy fruit. And then, you have to pull out the mango hairs from your teeth using floss, afterwards,” Chowdhury said.

The earliest name given to the mango was ‘Amra-Phal.’ In ancient India, the ruling class used names of mango varieties to bestow titles on prominent figures, such as the naming of a famous courtesan of Vaishali city to ‘Amra Pali.’ Early Vedic literature also referred to the fruit as ‘Rasala’ and ‘Sahakara.’ Mangoes have also been written about in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and the Puranas, two of the main scriptures of Hinduism. The name was translated to ‘Aam-Kaay’ in Tamil when it reached South India, and gradually changed to ‘Maamkaay’ due to pronunciation differences. The Malayali people further changed this to ‘Maanga.’

The Portuguese were fascinated by the fruit on their arrival in Kerala in the 15th century and introduced the fruit to the rest of the world as ‘Mango.’ The Portuguese established an international mango trade and grafted specimens of trees which led to the creation of the Alphonso variety, named after Portuguese general Alphonso de Albuquerque. While many other varieties are now lost, the Alphonso variety remains extremely popular.

Because of the mango’s large center seed, the fruit relied on humans to transport them across the world. While the Portuguese explorers introduced mangoes to Brazil in the 16th century, Persians carried mangoes across western Asia and planted seeds in east Africa. Mangoes were not grown in the United States until the 1800s. Today, despite being grown in almost all continents, India remains the top producer of mangoes, accounting for 50% of the world’s mango production; of every ten mangoes in the world, four are produced in India.

In fact, Saamiya Ahmed ’22 has a direct connection to the cultivation of mangoes. Ahmed’s family in India produce their own mangoes in a family owned mango orchard called “The Mango Belt.” Ahmed’s grandmother, Habiba Khan, is one of the main owners of the orchard.

“We live in New Delhi, but our weekend farmhouse is 75 miles east in the state of Uttar Pradesh,” said Habiba Khan. “We bought the orchard around five years ago. The orchard must be about 15 years old.”

“Mango trees take several years to mature, so they are started from grafting to ensure good fruit, smaller seed (pit), and speed up the process,” explained Ms. Khan. “The best time to plant a graft is in the monsoon season — that is July through August. Once mature, the trees start to flower around February and March as the weather warms up. Before that we de-weed the orchard, irrigate it, and use some natural fertilizers and organic pesticides. By April, you can see the unripe mangoes and you need to start saving them from monkeys! Around May and June, it is hot here, and the fruits start to ripen.”

The Khan family usually sells some of their produce, keeps some, and distributes the rest as gifts. To successfully sell them, “you need to pick the mangoes before they ripen fully,” said Ms. Khan. “This makes transportation easy and gives a window of a week to package and ship or sell. The picked mangoes are packed in crates and then tractors take them to the nearest wholesale fruit marketplace. From there it goes to other cities and may end up in different countries.”

For Ms. Khan and her family, “The Mango Belt” orchard holds a special place in their hearts. “We wait the whole year for the mango season and to have mango parties. It connects us to our older generations, since our great grandfathers also owned mango orchards, but further east.”

Ms. Khan also acknowledged the significance of mangoes in Indian culture. “There are many idioms, jokes and anecdotes centered around mangoes, even poems. There are stories from the lives of Kings in the Indian subcontinent about their love for mangoes. There are so many varieties of mangoes and their names are so interesting and deeply attached to the people, culture, and language.”

Cultural Significance

In India, the mango is an intrinsic part of the country’s culture, found in religion, art, poetry, and literature. Mango leaves are seen as a symbol of good luck and are strung up over the front doors of homes, especially during weddings and celebrations. Ganesha, the elephant deity, is often shown holding a ripe mango in one hand which symbolizes prosperity.

Mangoes have been used in art and fabrics for centuries as well. The iconic paisley pattern, often found in saris, kurtis, and other clothing, is said to be a stylized depiction of a mango. Mango leaves, fruit, and wood are also used for certain holy fires for celebrations in Hindu mythology and ritual.

Jain and Buddhist texts also mention the sacredness of mangoes. There are many references to Buddha meditating and performing miracles under mango trees. In one tale, Buddha is said to have made a white mango tree appear out of thin air and, as a result, Buddhists still consider the mango as a beacon of knowledge and peace. In Jainism, the Goddess Ambika, the harbinger of wealth and prosperity, holds a bunch of mangoes in her hand, which represent fertility.

The mango tree is also known to symbolize eternal love and wealth. An ancient Vedic story follows the romance between a king and a cursed princess who died and manifested into a mango tree from her ashes, symbolizing her radiance and beauty. Mangoes, to this day, still seem to bloom love wherever they go.

Emperors have coveted it, poets have penned its virtues, and ancient forts have its shape engraved on their walls. The Indo-Persian poet Amir Khusrow deemed the mango to be “Naghza Tarin Mewa Hindustan,” — “the fairest fruit of India.” From the pages of sacred Hindu texts to the courtrooms of the Delhi Sultanate, the mango has been a pivotal part of South Asian culture for centuries, and it will continue to share its magic for centuries to come.

Urdu poet Akbar Allahabadi summed up the delight of mangoes in the following plea in a letter to a friend:

“Neither letter nor message from my beloved send to me,

If you must send something this season, mangoes let them be.

Make sure these are some I can keep to eat another day,

If 20 be ripe, add another 10 that can stay.”

“There are many idioms, jokes and anecdotes centered around mangoes, even poems. There are stories from the lives of Kings in the Indian subcontinent about their love for mangoes. There are so many varieties of mangoes and their names are so interesting and deeply attached to the people, culture, and language,” said Habiba Khan, one of the main owners of the orchard ‘The Mango Belt.’

Paromita Talukder is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey’ where she explores topics ranging from online activism to clubs at Bronx Science. She sees...