King of New York: How Robert Moses’ Will Became New York’s Way

The infamous city planner’s rise to power and the contradictions buried within his legacy.

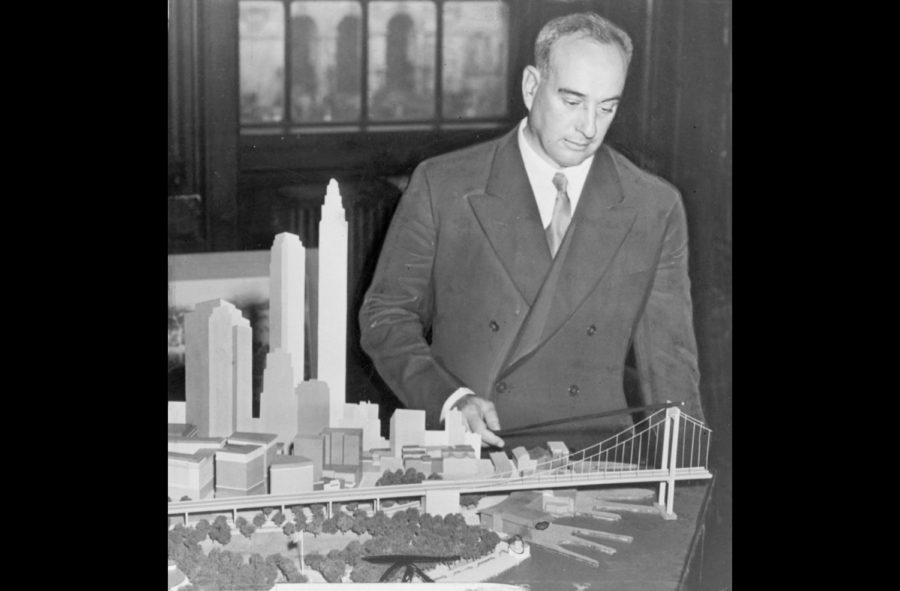

FC.M. Stieglitz, World Telegram staff photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Robert Moses presided over the 1964 World’s Fair, located in Flushing, Queens. In this photo he is standing over the Panorama, a full, to-scale, model of New York City which resides in the Queens Museum today.

New York City is constantly changing. Buildings go up, come down, undergo renovations, all in what feels like the blink of an eye. In what seems like a matter of days, the diner you walked by every morning becomes an empty lot, and the next time you pass by it, plants are sprouting out from between the bricks.

In the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, New York underwent rapid changes, with miles of highway, over a dozen bridges, and acres upon acres of parkland being built. The Triborough, Bronx-Whitestone, Henry Hudson, Throggs Neck and Verrazano Bridges were all built in this era, alongside the Midtown Tunnel, Cross Bronx Expressway, and West Side Highway. All of these projects, and many more, were major construction projects, costing large sums of money. Each undertaking allowed more access for cars in New York City. And all were spearheaded by Robert Moses, a man infamous for his complex legacy as city planner and parks commissioner.

Moses was born to a wealthy family in 1888 and lived in New Haven, Connecticut for about ten years, when, following the death of a relative on his mother’s side, the family relocated to New York City. Upon his graduation from high school, he enrolled at Yale University, where he played multiple sports and was deeply involved with the school. He graduated with his BA in political science, then went overseas to Oxford for his Masters in public administration. After earning a PhD from Columbia in 1913, he took his first steps into government.

Robert Moses’s rise to power was defined by close relationships with his fellow public officials. Governor Al Smith, who had been impressed by Moses’s work drafting major reform bills, began appointing Moses to various posts once in the governor’s mansion. Smith spearheaded a reorganization of the state government, and Moses worked right alongside him through the changes. Moses was intelligent, but more importantly, he was incredibly driven and would stop at nothing to turn his plans into reality. He established a reputation as an effective government worker, where Smith described him as “the most efficient administrator I have ever met in public life.” During this time, he began work on the large public works projects he would become famous for.

Once appointed Secretary of State in 1927, Moses became a master of holding onto what power he had and using it to garner more. With the positions he held at the time, he would carve out more power and responsibilities for himself. Never in his career was he elected to office, but he managed to gain more and more positions nonetheless. He built parkways stretching from Manhattan, through the outer boroughs, and into Long Island and Westchester, with little to no oversight. The amount of land in New York City devoted to parks skyrocketed, and Jones Beach on Long Island was groomed into a weekend retreat for middle class New Yorkers.

When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt passed the New Deal, money for state governments came flooding in. This money was intended for public works projects, which would create jobs for Americans during the Great Depression. When this money came to Albany, Moses knew what he wanted to do with it. He was appointed to the role of NYC Parks Commissioner in 1933, and quickly began work on infrastructure projects like parks, playgrounds, and bridges.

The next year, he made one of his few glaring political missteps, running for governor and losing to Herbert Lehman by a large margin. Even his own allies, like Al Smith, were backing Lehman and the campaign was hopeless. His attempts to tie his opponent to the Lehman brothers failed — especially given that Moses had links just as strong, if not stronger, to the banking duo.

After a brief loss in power following Lehman’s election, Moses quickly rebounded using his ties with others in power and immense ambition. He continued pushing for more highways, bridges, and parks, but all the development Robert Moses brought to New York came at a price. His freeways cut through and bulldozed low income neighborhoods in the outer boroughs, and a lack of oversight kept anyone from stopping him.

In 1974, Robert Caro published The Power Broker, a 1,300 page tome detailing Moses’s career. By the time the book came out, Moses’s power was gone — throughout the 1960s he relinquished title after title, until suddenly the man who once held 12 consecutive roles in New York’s government had nothing. In the book, Caro details the abundant racism in Moses’s projects and the ways his car-centric vision of New York left low-income New Yorkers behind.

His parkways — the West Side Highway, Cross Bronx Expressway, and Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, to name a few — made it easier to get around the city by car, but he neglected, even actively steered money away from, public transportation. He ensured the bridges stretching to his Long Island beaches could not support the heights of buses, keeping those reliant on public transportation away.

All those parkways required land to be built on, and unfortunately for the people living where he wanted to build, Robert Moses was not a fan of compromise. He established the Sheridan Expressway in the Bronx, which was meant to serve as a connector between the Boston Post Road and the Bruckner Expressway. The building of the Sheridan took a while to get started, but when Moses began to mobilize, he ran into a conflict. The land he wanted to use was going to be used for middle-income housing, and the people working on this housing asked him to reroute the Sheridan to allow their buildings to be constructed. This parcel of land was under the control of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, chaired by none other than Robert Moses.

When asked to relocate, he informed the group that this was really a matter for the Parks Department, which he also headed. He sent the project back to the Bridge and Tunnel Authority. He continued to bounce the project back and forth between the two agencies for around a year until the group gave up, already demoralized and disparaged from the fallout of Moses’s Cross Bronx Expressway.

Robert Moses truly was the king of New York: given the reins by the men in power around him and able to enact his vision piece by piece.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, he was described as arrogant and unwilling to listen to others. One of his moves was, in response to pushback from a decision in one of his roles, to threaten resignation in another to try and force anyone challenging him to back down. In the end, this sparked his downfall — a new mayor was more than willing to accept his resignation and a shell-shocked Moses did not know how to take back what he had done. In 1959, he handed over many of his titles in order to spearhead the World’s Fair effort (a sequel to the 1939 World’s Fair which had added Flushing Meadows-Corona Park to Moses’s list of creations) and the rest of his roles disappeared throughout the 1960s.

Today, the view of Robert Moses in public perception is overwhelmingly negative. The Power Broker, reexaminations of the racism embedded into his construction projects, and new perspectives on the pitfalls of a car-centric city have all played a role in this view, which comes as a stark contrast to the adoration New York had for him during the peak of his career. While a portion of Jones Beach is still named for him, some of his works—such as the Sheridan Expressway—are being reconsidered and taken down.

Moses’s legacy is a double-edged sword, both building incredible infrastructure projects and causing immense harm to the people living in the city he claimed to serve. No matter your opinion of him, he had a massive impact on New York and understanding his career sheds light on why this city is the way it is. One question Robert Caro could not answer in all 1,300 scathing pages was what direction would New York have gone in without the influence of Robert Moses. We will never know.

Robert Moses truly was the king of New York: given the reins by the men in power around him and able to enact his vision piece by piece.

Lily Zufall is an Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.’ To her, the most appealing part of journalistic writing is being able to walk the line between...