Peter Turchin: The Magnetism of Mathematical History

Why the man who can predict the future is (most decidedly) not a prophet.

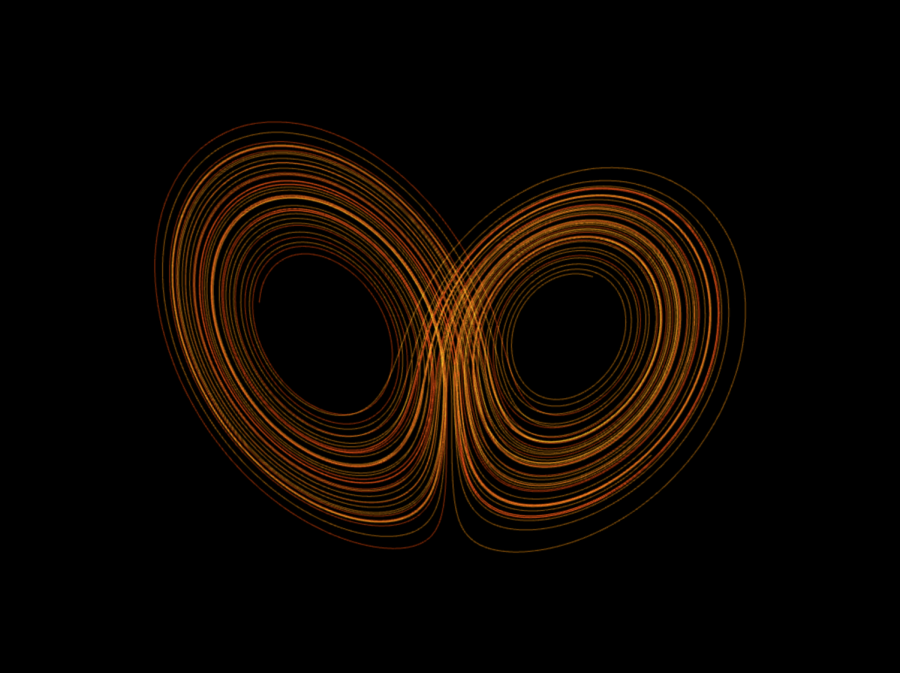

The Lorenz Attractor is extremely sensitive to initial conditions. A negligible change in the starting point of one of its orbiting particles will change its trajectory entirely, but each set of initial conditions generates only one unique graph. This illustrates the apparent paradox that the universe can be both deterministic and wildly unpredictable.

The chaos of 2020 launched Peter Turchin from relative obscurity into the spotlight. In 2010, Turchin made the startling prediction that “the next decade is likely to be a period of growing instability in the United States and western Europe,” a statement which he supported with statistical data analysis of past historical trends.

The astonishing accuracy of his foresight, substantiated by the tumultuous socio-political events of this past year, have given rise to his sudden notoriety. Turchin’s mathematical history — a field coined “cliodynamics” — has now ascended into the realm of academic renown, captivating audiences with its ability to anticipate the future.

It is rare for an academic like Turchin to grace the pages of The New York Times, The Atlantic, Forbes, The Economist, and The Washington Post all in the span of a few months. What is even more unusual is that Turchin is not merely lending perspective to a topic in which he has expertise, or contributing to an overarching narrative that extends beyond his persona. He has become the story, the focal point, a figure whose work has garnered so much intrigue that journalists across the country are convinced that he is altering the current trajectory of history.

But Turchin is somewhat displeased with this attention. He feels that his newfound publicity, tainted by exaggerated rhetoric and sensationalist shock-value, has depicted a warped version of his work. On his website’s blog, he frequently posts critiques of pieces which he believes are misrepresentations of what it is, exactly, that he does.

Regarding a recent Atlantic story which portrays him as the “mad prophet of Connecticut” (featuring artwork of the Greek deity Apollo, oracle style, laurel-wreath and all), Turchin writes, “I am not a prophet, [and] never claimed to be one. In fact I ha[ve] specifically written about why I eschew prophecy, and am on record criticizing other ‘prophets.’ As a scientist, I use scientific prediction as a tool to test theories.”

Evidently, the “prophet” characterization is one that has plagued him for much of his research career. In a blog post dating back to 2013, he writes, “CLIODYNAMICS IS NOT ABOUT PREDICTING THE FUTURE!,” wielding punctuation and capitalization to convey his frustration through the screen.

“Cliodynamics, instead, is about understanding why and how social systems change,” Turchin explains. “We look for general principles (‘laws’, if you will), and build mathematical models based on these principles. Then comes the most critical part – testing model predictions with historical data so that we can tell which are correct, and which are not,” he adds.

This systematic collection of historical data allows Turchin and his peers to objectively compare different historical theories, addressing a problem with current historical mediums that Turchin first diagnosed, and now strives to rectify. “History is a wonderful discipline. A lot of reading history books, that’s why I got into history,” Turchin notes with a smile. “Traditional historians have done a great job describing past human societies and how they [have] changed. The problem is not that there are too few explanations — in some sense, there are too many.”

To illustrate this idea, Turchin points to the German historian Alexander Demandt’s 1985 book, “Der Fall Roms,” which compiles the vast number of theories that aim to explain Rome’s demise. Demandt ended up with a list of 210, rife with contradictions: asceticism (11) and hedonism (90), Christianity (32) and polytheism (157), militarism (135) and lack of army discipline (125).

Although Turchin acknowledges that incongruence is inherent within dynamic societies, he contends that “not all of [Demandt’s 210 theories] can be correct. What we need is some kind of mechanism to decide which are better and which are worse, and we do that by empirically testing theories. Cliodynamics is history as science. [As] cliodynamics [progresses], we should see a cemetery of bad theories. Only the better ones will be left standing.”

To solidify cliodynamics’ standing in the world of academia, Turchin created an eponymous scientific journal that publishes two issues per year. The journal covers topics ranging from recent foreign upheavals (“The Causes and Mechanisms of the Ukrainian Crisis of 2014: A Structural–Demographic Approach”) to macro-level studies of American trends (“A Cultural Evolution Model for Trend Changes in the American Secular Cycle”). All research funded by the journal takes advantage of Turchin’s second noteworthy endeavor, “Seshat,” an archive of historical and archaeological data spanning millennia.

Joe Manning, Turchin’s collaborator on the Seshat project, and a Professor of History at Yale University, elucidates the significance behind the archive’s carefully chosen moniker, “Seshat is an Egyptian deity, a goddess. Her name comes from the ancient Egyptian word ‘to write’,” he says. “‘She who writes’ is the literal translation, but [Seshat] is really in charge of the technical aspects of writing: cataloging and recording. She was the goddess of —really the first in the world— of what we now call databases.”

To Turchin, transforming history into a data-based medium is a logical next-step in expanding the field’s horizons, “Few people outside of dedicated professional historians know much about the full sweep of our collective past. We are used to thinking about the past in terms of stories of ‘great rulers’ or major battles, but we think of our own world largely through data: the key facts and figures that reveal how modern societies function,” Turchin says.

“So [although] prediction is instrumental – it is subordinated to the main goal, that of understanding. The chief purpose of mathematics is to make sure that predictions really follow logically from the premises,” he writes.

Turchin first discovered his love for mathematics in his early childhood, living under the jurisdiction of Soviet rule. Turchin’s childhood home of Obninsk was a haven for scholars, harboring dissidents like his father Valentin, a philosopher-scientist who was eventually forced to flee the USSR in 1978.

Turchin indicates how lucky his family was to have escaped unharmed, “Others ended up in prisons,” he says. “By 1980 the Soviet Union looked like a monolith that was immune to both external and internal challenges.”

Mr. Fomin, a beloved calculus teacher at Bronx Science who, like Turchin, grew up in the USSR, contextualizes why so many Russians were drawn to mathematics under Soviet rule. “I don’t think it is a mere coincidence that one of the best schools of theoretical mathematics was created in the former USSR, and general math education was so well developed and successful there,” he said.

“Imagine a place where schools and colleges — instead of serving as institutions of learning — became the places of indoctrination into the dominant ideology. Imagine a society that constantly rewrites history books, because it sees history not as a heritage that needs to be understood in the context of its time, but merely a tool to control the future. Imagine a country where all papers and television stations coalesced into one giant echo chamber,” Mr. Fomin explains.

“Now you can begin to understand what kind of country the USSR was. Mathematics became one of the few, select outlets not tainted by corrupt ideology; [a field] where people could pursue objective truth and freely exchange ideas,” he writes.

Perhaps Turchin, too, found refuge within the indisputable truth of mathematics, within its certainties, existing beyond the fabricated reality of Russia’s post-Stalinist government. It is possible that the intractability of mathematics, its refusal to acquiesce to the will of mankind, was alluring to a young Turchin, who like Mr. Fomin, clung to any remnants of objectivity he could find within a country tarnished by blatant untruths.

Turchin’s contempt for the weaponization of history at the hands of the corrupt continues to inform his ideology. He embraces mathematics as an ideal medium for recording history because its use of large-scale data sets prevents those in power from cherry-picking narratives tailored to individual agendas.

Mr. Fomin agrees that this wide-angle approach to history is advantageous, “It can be just as misleading for a researcher to give too much credence to isolated data points, as it is to assign outsized importance to anecdotal evidence and personal experience. While grounding new topics and problems in students’ personal experience can help to make them more accessible in a secondary school setting, limiting discourse to an isolated data point —assigning it disproportionate weight — can have a stifling and misleading effect,” he writes.

Mr. Fomin concedes that while an “objective, mathematical perspective of history will likely be liked by no one, it might give us much needed balance and continuity.”

Mr. Fomin’s conjecture is correct. Turchin’s attempt to adapt history, a field which leans into subjectivity and disavows generalizations — into an objective science — has generated controversy among academics. And concerns that a scientific history would fail to represent experiences which deviate from established norms bear weight: when a set of data does not adhere to a singular equation, scientists analyze the general trend and reject nonconforming outliers.

It is fortunate then, that Turchin is hyper aware of history’s responsibility to reflect all perspectives, including those that are systematically excluded from mainstream narratives. Those who critique Turchin’s work on the premise that cliodynamics attempts to radically transform history possess a fundamental misconception. Turchin does not wish to abolish current narrative-based historical mediums, which center the stories of marginalized people, and laments articles which inaccurately portray his motives.

“My view of history and historians (and archaeologists, religion scholars) is appreciative and respectful. I have written on many occasions that cliodynamics needs history. The success of the Seshat project critically depends on collaboration with expert historians and archaeologists,” Turchin says.

By working with historians and incorporating their feedback, Turchin creates a system of checks and balances, ensuring that cliodynamics abides by the principles which guide responsible historians. “Our knowledge about past societies has many gaps and a lot of uncertainty — this uncertainty needs to be reflected in data so our analytical results represent not only what we think we know, but also the limits of our knowledge,” he explains, exhibiting attentiveness to the reality that literacy, and access to the public sphere, have been historically reserved for the societal elite.

“Far from abolishing History, or forcing it to surrender, we want history to flourish. We need academic historians to use their expertise to continue amassing the knowledge about different aspects of past societies. We rely on historians and archaeologists to interpret complex and nuanced historical evidence, before it can be translated into data for analysis,” Turchin said.

Beyond the academic world’s reticence, much of the fear surrounding Turchin’s work arises from the results of his data analysis: projections that society is hurtling towards a dismal future. Because cliodynamics identifies cyclical patterns across time, Turchin’s estimates of potential futures are wrought with the calamities that have plagued civilizations throughout human history.

But cliodynamics is not a predictive science, and Turchin is not a prophet. Although his prediction for 2020 came true, Turchin’s forecasts do not reduce individuals to agentless pawns, condemned to play out deterministic futures. “Making precise predictions about events in human societies decades or centuries in the future is just science fiction,” he said. “By exercising a multitude of choices throughout our lives, we constantly derail the course of future history in unpredictable directions.”

Turchin alludes to the “butterfly effect,” a phenomena in chaos theory first described by mathematician Edward Norton Lorenz, and later popularized by Ray Bradbury, to illustrate the extent of individual influence. “Exercising one’s free-will can have major consequences at the macro level, just like a butterfly fluttering its wings can affect the course of a hurricane,” he said.

“However, such optimism should be tempered by realism,” he added. “Although each of us probably affects the course of human history, most of us have a very slight effect, and any large effects are probably a result of a completely unforeseen concatenation of events.”

It is the combination of individual free-will and systemic forces that engender future outcomes. “You can see it vividly if you play with a model that is in a chaotic regime, for example on a Lorenz attractor. The trajectory is constantly modified, but it still remains on the chaotic attractor,” Turchin said.

Realizing that advanced mathspeak may be inaccessible to those unfamiliar with differential equations, he changes course. “To put it in simple terms, if you have a peak coming, then individual actions can delay it, or advance it; make the peak a little higher, or a little lower. But there will be a peak in one form or another,” he said.

The bleak events which Turchin’s models anticipate will exist as potential futures regardless of our choice to be conscious of them. What we can control is whether or not we confront what lies ahead, reach into the murky unknown, and exert all the agency we possess — even if that means minimizing the amplitude of a relentless wave, as it trends towards immutable disaster.

“So the ‘bad news’ is that the future is unpredictable,” Turchin writes. “But, prediction — or, rather, prophecy — is overrated. What’s the use knowing that doom is upon us, if there is nothing you can do about it? Wouldn’t it be better to understand the causes of the looming danger, so that we could take steps to avoid this undesirable future?”

“Making precise predictions about events in human societies decades or centuries in the future is just science fiction. By exercising a multitude of choices throughout our lives, we constantly derail the course of future history in unpredictable directions,” Turchin said.

Enza Jonas-Giugni is a Features Editor for 'The Science Survey,' where she edits long-form articles on topics ranging from politics to portraits of Bronx...