Soaring Above: The Wonders of Paragliding

With nothing but a canopy and harness in the sky, paragliding has redefined air sports and what it means to experience the freedom of flight.

My pilot, surprisingly, trusted me enough to hand me the GoPro in the air. Pictured below are the Ölüdeniz Blue Lagoon, Butterfly Valley, and the city of Fethiye behind the mountains, all in the country of Turkey.

The drive up Mount Babadağ was bumpy, to say the least. With potholes, sharp turns, and a road so narrow that the bus was nearly driving on air, the 30-minute ride seemed to go on forever. I remember sharing a look with my mother, saying nothing but our eyes communicated it all: was this really worth it?

The takeoff point — 6,500 feet high, to be exact — overlooked the Mediterranean coast of Turkey, giving way to the Aegean Sea and the village of Ölüdeniz below. I felt the adrenaline rush through my veins, at the same time as my legs turned into jelly.

“Your first time flying?” My pilot, Serdar, asked as I strapped on my harness. I nodded. “Same here,” he joked. Upon seeing my evident tension, he added, “25 years.” I smiled, but my fear of heights still lingered.

In hindsight, my nerves were nothing more than a rite of passage. Takeoff was instantaneous: a few seconds spent running off the side of a mountain, and we were in midair.

The flight duration was 30 minutes — around the same length as the bus ride up the mountain, but this time, I didn’t want it to end. From aerial twists and turns to lightly sailing through the air, being tied to a parachute in the middle of the sky felt surprisingly idyllic. Before I knew it, we were in descent: it was over.

Taking Flight

Paragliding is a competitive and recreational air sport, first designed in the early 1960s by pilot David Barish. Originally named the “Sailwing” in the 1950s, the parachute was intended to facilitate the return of NASA space capsules back to Earth, a recovery that would push the United States ahead in the U.S.-Soviet Space Race. Despite a lack of support from NASA, Barish’s design caught the attention of other pilots and builders. The “Parafoil,” an improved prototype, was patented in 1964, and, in 1978, the first paraglide took off in Mieussy, France.

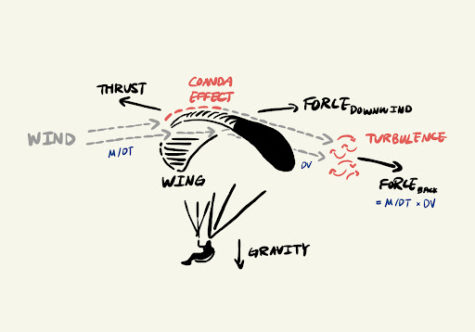

At first, not many people were receptive to the concept of paragliding. How can a paraglider stay in the air for hours at a time while skydiving parachutes float back down to Earth? At its most foundational level, the design and flying capabilities of paragliding can be traced back to the core of aerodynamics: Newtonian physics.

A paraglider wing may seem similar to that of an airplane, but the two are often incorrectly equated. The main difference lies in the method of force generation: whereas airplane wings produce active force and cut through the air, a paraglider’s wings primarily use passive generation, where it acts as a reaction to forces in the wind and transfers momentum to float at a slower speed. Risers, lines, and brake controls allow the pilot to steer the glider in certain directions and complete aerobatic maneuvers, but many pilots embrace the unexpected and allow the air to navigate their flight.

While paragliding is grounded in science, the physics of lift is still at the center of much academic debate — there is no universal formula or theory that explains exactly how the aircraft achieves flight. In the meantime, the materials and design have constantly undergone the process of further development. To minimize drag and optimize aerodynamic efficiency, the paraglider wing (or “canopy”) is made of lightweight, tearproof fabric and structured in an oval shape. Most recently, manufacturers have begun experimenting with carbon fiber canopies in order to make paragliders even lighter.

Like all other air sports – such as hang gliding or skydiving – paragliding has its dangers, where a glider could crash or encounter extreme weather. Uniquely, however, its innovations and safeguards make it also one of the most accessible. Since every flier is equipped with a pilot, no prior training is necessary; people of all ages, including people as young as two years old and as old as 104 years old, have participated in the activity. The passenger sits in the “harness,” or an armchair-like pod attached to the parachute with strings, while the pilot is tied right behind them and controls the navigation. Flights are typically around thirty minutes to an hour, but solo paragliders can often stay aloft for three hours or more. Electronic devices like altimeters and GPS, as well as built-in safety features like automatic stabilizers and wingtip steering, have reduced the risk of accidents and served as comfort to many.

This assurance of safety is also largely afforded by a paraglider’s freedom in the air. The fabric canopy and non-rigid frame allow the pilot a greater degree of maneuverability, compared to glider wings that utilize solid material like fiberglass. It is not completely “free-flying,” however, due to passive force — every flight has its own air conditions, and thus, its own detours. No one trip is the same.

Where To Paraglide

Takeoff usually happens on higher ground, such as a mountain or slope. After inflating the wing, the flier and pilot run into the air — known as the “forward launch.” A typical flight is around thirty minutes, which can either involve slow, light floating, more extreme aerobatic maneuvers, or both. In any instance, the adrenaline rush offers the same thrill, and the world underneath is equally breathtaking.

In Switzerland, paragliding takes place over the Swiss Alps. Interlaken, a town of just over 5,000, is surrounded by the Bernese Alps and is dubbed the adventure capital of Switzerland. From paragliding and skydiving to river rafting and bungee jumping, it is a hotspot for all those who seek a thrill.

Three thousand miles away, on the Turkish Riviera, the resort town of Ölüdeniz is for the more laid-back. The bay is known for its beaches and lagoon; cafés, sunglasses vendors, and hotels line the streets. Paragliding, thus, became popular as well, with Mount Babadağ serving as an ideally situated takeoff point.

There are no strict guidelines for what constitutes a paragliding site, except for flying over private land or restricted airspace. As a result, paragliding has gained pull all around the world: from Queenstown, New Zealand to Pokhara, Nepal, the sky is no longer a limit — it is an invitation.

Careers and Championships

Paragliding’s accessibility draws in not only tourists and passengers, but new pilots as well. Compared to other air sports, it poses relatively fewer dangers and requires minimal training.

“I have become more fearless,” said Aryan Kasbekar, who became India’s youngest paragliding pilot at ten years old. “[It’s] another level of happy, I couldn’t explain it.”

Most professional pilots either teach at paragliding schools or fly competitively at championships around the world. Typically spanning over a few days, these competitions are open to all — whether it be a 30-year veteran pilot or someone who’s new to the activity. The Ozone Chabre Open, for example, takes place in Laragne, France, and is in its 16th year. Instead of reinforcing a strictly competitive environment, it seeks to provide a more easygoing learning and social setting. On the other hand, the PWCA (Paragliding World Cup Association) held the first leg of the Paragliding World Cup in Castelo, Brazil in March 2023 catering to more competitive pilots. The Association will then move throughout the rest of the world, relocating to Spain in May and South Korea in October.

Paragliding has evolved over the years, but at its core, it is simply another way to see the world. Most who enjoy paragliding are not full-time pilots or adrenaline junkies — in fact, they often come from completely different backgrounds and cultures. Yet they share a somewhat indescribable bond: knowing that while the fear of the unknown is always present, the initial thrill of running into the air makes every trip worthwhile.

As my feet touched back down on Ölüdeniz Beach, my adrenaline levels eased. Paragliding might have been a once-in-a-lifetime, exhilarating experience for me (although I’ll be flying again as soon as I can), but for my pilot, his colleagues, and over 200,000 pilots in the world, it is the constant in their lives.

Because above the views and the adrenaline, paragliding is a community: filled with fear and courage, creativity and craft, and people who make it their life’s activity.

Paragliding is not completely “free-flying,” however, due to passive force — every flight has its own air conditions, and thus, its own detours. No one trip is the same.

Charlotte Zhou is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ In addition to writing and editing articles, she constructs the online crossword and...