New York City is in crisis.

Walk ten blocks anywhere in the city, and you’ll see ten different communities with ten different cultures and ten different economic situations. Today, you might also see more unhoused New Yorkers than ever before, as one of the worst housing crises in New York City history coincides with a historic influx of migrants.

New York has rapidly become unlivable for many of the people who call it home, as skyrocketing rents and transportation costs push lower-income and middle-income New Yorkers either out of the city or onto the street.

THE HOUSING SHORTAGE

We are in the midst of the worst affordability crisis in more than two decades.

The median New York City household now spends 35% of their income on rent, as opposed to the national median of 30%. The median cost of newly rented apartments in Manhattan has reached a record high of over $4,000 dollars a month. More than half of New Yorkers can’t comfortably afford rent, transportation, food, and healthcare. A record 61,000 New York City citizens are currently unhoused.

Lisette Nieves, president of the Fund for the City of New York, told The New York Times, “People are doing everything they were told to do, but they still cannot afford to live here. I feel like we’re representing a broken contract with people.”

One key factor driving up costs is a shortage of housing units in the city – as it stands, we quite literally do not have enough apartments to accommodate New Yorkers. The current vacancy rate is about 3%, the lowest of any major American city. The consensus among researchers is that a limited supply of housing units is leading to rent hikes and increasing our homelessness rates.

In addition to increasing rents, the cost of living in New York City is rising at an alarming rate. Grocery store prices are higher now than they were just a year ago by approximately 5 to 6%, and transportation costs are up after yet another subway fare increase in August 2023.

As of April 2023, according to The New York Times, households in all five boroughs need a base income of $100,000 per year to have money left over after expenses, but the median household income is only about $70,000 per year.

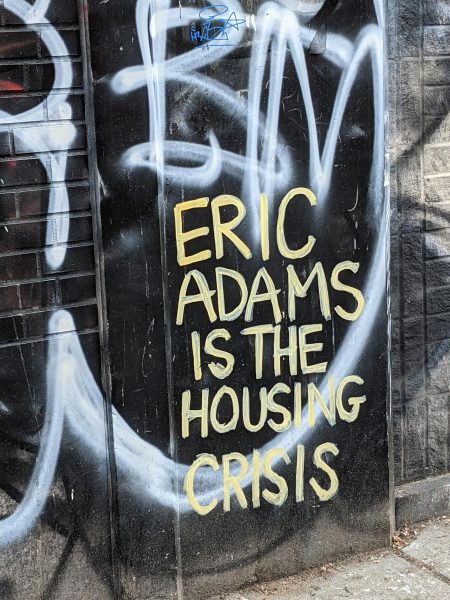

Many New Yorkers are frustrated with Mayor Eric Adams’ response to the situation. Research shows that one of the most reliable ways to keep down rents is to build more apartments, but New York City isn’t doing that. The Adams’ administration has pledged to approve more infrastructure plans, but many sources report numbers as about the same as the previous administration – even as the demand for housing in New York City has risen sharply.

Notably, however, it’s difficult to find accurate data on housing project approval and construction. The Adams administration boasts record high numbers, while Rachel Fee, executive director of the New York Housing Conference, told The New York Times, “We’ve seen the city’s housing production decrease by 43% just in one year alone… There are real significant challenges ahead.” Understanding the scope of our housing shortage, and our government’s response to it, is critical – we need accurate, widely available data on what exactly the city is doing to help homeless New Yorkers.

Zoning policies and complex permit processes promote the construction of single-family homes or luxury apartments at the expense of more accessible housing. Many areas of the city require new developments to provide off-street parking, garages, or backyards. This makes it harder to approve new affordable developments. Neighborhoods without these zoning restrictions have “added more housing and contained rent growth.”

Changing these regulations is no small feat. The Adams administration is experiencing a staffing shortage — the city’s overall workforce has dropped by nearly 20,000 employees in just two years — and nowhere is that more pronounced than in the housing sector. Even minor staffing shortages harm productivity, and with a quarter of positions empty at the Department of Buildings, it’s not much of a surprise that new housing is coming too little, too late.

THE MIGRANT CRISIS

The New York City housing crisis is more than the result of a worsening economy and outdated legislation. Newfound urgency was added to the situation starting in the spring of 2022 when migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean – mostly Venezuela, Columbia, and Ecuador – started pouring into the city.

The Venezuelan economy is declining at unprecedented rates. The situation in Venezuela is the second-worst external displacement crisis in the world right now. Already, about 7 million refugees have left, and many of them have sought asylum in the United States.

This doesn’t explain why so many of them are ending up in New York City. While we are famously a city of immigrants, other cities like Los Angeles and Houston are typically also popular destinations. Texas Governor Greg Abbott is largely to thank for the uneven distribution of refugees. In an attempt to provoke national outrage and force the federal government to restrict immigration, Abbott has been packing thousands of migrants on buses to New York.

The city is flailing under the pressure of the over 60,000 new New Yorkers. The city has spent over a billion dollars providing resources to immigrants in the past year, but we’re nowhere near close to an adequate response. A record 100,000 people are in homeless shelters, about half of whom are migrants.

Very quickly, the city ran out of housing units, meaning that for the last few months, migrants have been put up in increasingly inhumane quarters. The city has bypassed regulations on shelters, no longer requiring access to stoves, private bathrooms, clean bedsheets, or even space between beds. Some families have had to stay in offices, school gymnasiums, and tents. The city is now reportedly considering housing people in the parking lot of a state psychiatric hospital.

One site under construction, Floyd Bennett Square, has garnered wide criticism from advocacy agencies. The Legal Aid Society and Coalition for the Homeless released a statement, writing that, “Sheltering families with children in cramped and open cubicles at Floyd Bennett Field not only raises serious legal questions but runs afoul of this Administration’s previous statements to provide safe and appropriate shelter to this extremely vulnerable population… Private rooms, not open cubicles, are needed to ensure the safety of families with children and to reduce the transmission of infectious disease, among other obvious reasons.”

The city has been unable to keep up with the increased demand for shelters, and recently the Adams’ administration has made some unexpected moves to keep numbers down. One of those moves was a trip that Mayor Adams took to three countries, Mexico, Ecuador, and Columbia, to meet with migrants and discourage them from emigrating to the United States. His administration also distributed fliers telling migrants: “Housing in N.Y.C. is very expensive. Please consider another city as you make your decision about where to settle in the U.S.”

Last month, the city imposed a 60-day limit for migrant family shelter stays, and just a few weeks ago Adams used the state of emergency to suspend New York’s decades-standing right-to-shelter policy. Unsurprisingly, Adams’ policies have garnered wide disapproval.

For one thing, many refugees don’t have working papers yet, and without them, migrants are denied access to above-board work. Some have applied for temporary work permits and are waiting to hear back, while others don’t have access to support in filing a request in the first place. For families who cannot yet legally earn a salary, a time-limit on guaranteed shelter is at best naive and at worst dangerous.

This suspension also sets a dangerous precedent, and many homelessness scholars are concerned that Adams’ decision will open the floodgates to limits on the sources of aid both migrant and non-migrant homeless people have in New York.

New York City has labeled itself a safe haven for anyone who needs one. We are a city of immigrants, a city of the unhoused and the poor, and we always have been. We need to provide for those people if we want to live up to how we represent ourselves, and if we don’t want to drive them onto the street — or out of their city.

New York City has labeled itself a safe haven for anyone who needs one. We are a city of immigrants, a city of the unhoused and the poor, and we always have been. We need to provide for those people if we want to live up to how we represent ourselves, and if we don’t want to drive them onto the street — or out of their city.