All That Glitters is Not Gold: A Modernizing India With Centuries-Old Ethnic Conflicts and a Problem With Fake News

While India builds gilded architecture in its prominent cities and influences the global scene, religious conflicts have bloody consequences in its everyday world.

The Times of India, CC BY 3.0

Firefighters put out a street fire during the 2020 Bangalore Riots, caused by an alleged blasphemous Facebook post by the nephew of an Indian National Congress state legislator targeting the Islamic Prophet Muhammad. Damages in the resulting chaos included looting, the burning of cars and police stations, three deaths, and the arrests of over 206 people.

India has recently made headlines for a plethora of reasons: its dynamic cultural scene, its global power plays, and its numerous military expansions. Yet, one of its most important headlines remains buried under a slew of picture-perfect articles lauding the country as the world’s largest democracy. Fake news articles reporting incidents of Muslim-led violence and promoting pro-Hindu religious propaganda have multiplied in scores, intensifying India’s deeply rooted ethnic conflicts.

Irony is at the center of the situation: while Prime Minister Narendra Modi conducts peace talks with Putin regarding Ukraine, advocating for human rights, he also backs misinformation in his own country in order to garner support for his discriminatory policies against India’s Muslim minority. Modi has bent the media, legislature, and civil society — institutions that once guarded India’s democracy — to his will. As he has done so, the country’s indispensability on major global issues has ensured little pushback from Western allies.

Hindu and Muslim tensions are at an all-time high in the nation, with reports of the brutal killings of both groups spreading like wildfire on social media. These acts of violence are then exacerbated by falsified news sources, and the cycle of hate crime continues.

Over 10,000 people have been killed in Hindu-Muslim communal violence since 1950, and countless more have suffered injuries and property damages. The conflict between the two has become a norm in the country, with a recent provocation occurring in October 2022 during the Navratri festivities.

Tensions between the two groups are deeply entrenched in the nation’s history. Many scholars argue that the conflict between Hindus and Muslims can be traced back centuries prior. For the contemporary answer, however, we can look to the division of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 post-British colonization.

Before the 1947 partition, evidence indicates that Hindus and Muslims peacefully coexisted in communal villages and cities. Religion was mainly practiced at home and was not a dividing factor between individuals as it is today. All of this changed when the British departed from the region, and various political groups of ideological nationhoods gained momentum. The lack of separation between religion and politics led to pro-religious zealots securing popularity within local political parties. At a time of mass anxiety, distrust, and public radicalization, lines between secularism and prejudice blurred, and religious division became increasingly prevalent.

Ms. Stephanie Kountourakis, a Bronx Science history teacher and founder of the school’s new Race and Gender course, offers insight into historical precedent regarding ethnic conflicts. While Ms. Kountourakis does not comment specifically on the Hindu-Muslim conflict, she explains in general, “Historically, the roots of ethnic conflicts are deep, and the byproduct of conflicts like these have included some of the worst examples of people being permanently displaced, killed, separated from families and/or violently harmed. Unfortunately, differences are sometimes perceived as threats and are viewed as threatening, thus making ethnic conflicts prone to the perpetuation of serious violence.”

Today, religious partitions continue driving a wedge within communities, with time only being an aggravating element.

Nonetheless, a new factor has emerged, which is the major contributor to, and oftentimes, the origin of the ongoing conflict in the 21st century — fake news sources. Spreading conspiracy theories, hate speech, sensationalism, and out-of-context photos, fake news sources exacerbate violence in the region and fuel the flames of instability. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, the media began to report false claims that Muslims were the true cause of the virus. Two years prior, in the summer of 2018, rumors circulated on WhatsApp group chats about a Muslim kidnapping gang operating in India’s western state of Maharashtra, resulting in a string of lynchings in the region.

“The ease and availability of misinformation is a huge problem,” Ms. Kountourakis continues. “I believe as a nation and global community we are only starting to experience the ramifications.”

The problem of fake news is not unique to India, but the effects are particularly amplified there due to the sociopolitical climate.

Over 900 million people use the internet in India today and are exposed to numerous fake news sources. However, this was not always a concern as political misinformation was never an issue this extreme before. It was when the Modi administration came to power in 2014, that the media landscape in India drastically changed.

As social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Whatsapp began to grow in popularity, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) quickly recognized the potential of these sites in influencing public perception. His administration spent millions of dollars funding propaganda campaigns on these platforms, targeting first-time internet users and those in rural areas.

As Dr. Sayeed Al-Zaman, Assistant Professor of the Department of Journalism and Media Studies at Jahangirnagar University articulates, “Ignorance plays an important role here; if a large share of people [in] a country is ignorant about politics, political misinformation strikes hard.”

This political misinformation directly benefits the Modi administration by promoting their fearmongering agenda and attracting support. Although other parties in India dabble in misinformation, none rival the Bharatiya Janata Party in extremity and effectiveness.

About 1.2 million volunteers helped run the party’s Whatsapp social-media campaign for the 2019 national elections. Based on research published in the Hindustan Times, eight of the ten most shared misleading images in pro-BJP WhatsApp groups pertained to claims that Congress, a political opposition party, favored Muslims and contained hateful rhetoric towards other minorities.

Part of the issue also stems from the cultural emphasis on religion in the region. India has been experiencing a rise in Hindu nationalism and the birth of the Hindutva movement — the belief in the hegemony of Hinduism in India and the establishment of the country as a Hindu, rather than a secular state.

A study conducted by Dr. Al-Zaman quantifies the percentage breakdown of different categories of misinformation in the country. The research overwhelmingly found that excluding the pandemic period, political and religious fake news made up the majority of media manipulation.

These results can be explained. In a multi-communal and multicultural society, if a state favors a selected community, it exerts adverse impacts and widens the avenues for subsequent crises. Religious misinformation might be a byproduct of such religious politics, coupled with the existing fears, taboos, and tensions in society.

Dr. Al-Zaman adds, “No misinformation becomes misinformation unless it has a certain amount of public interest. But when misinformation is connected to issues of tension and fear, it becomes a problem.”

But Modi’s campaign against Muslims is not just limited to the press. It has been codified in his policies as well. Passed in 2019, The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) only protects the rights of non-Muslim immigrants and refugees from neighboring Muslim-majority countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Passed by Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party majority in the highest vote share by a political party since the 1989 India general election, the act deliberately excludes Muslims from seeking refugee status, leaving them vulnerable to deportation or jailing.

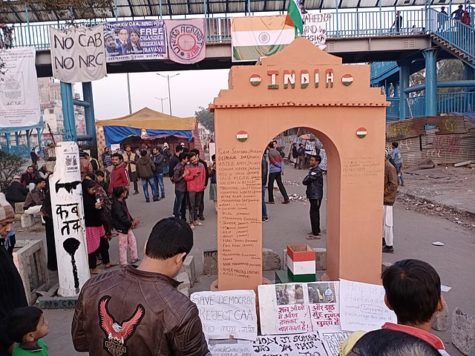

Following the act’s ratification, demonstrators took to the streets in opposition to the legislation’s blatant discrimination. Peaceful opposition quickly turned into violent mass shootings and brutality, however, as the Modi administration deployed riot control squads to mitigate the backlash.

Despite this, there is negligible opposition from Western countries due to India’s strategic alliances and significance as a key player in the region. The country is a rising economic force, housing the world’s fifth-largest economy, and well-positioned to prosper with its improving trade ties, large youth population, and expanding technological infrastructure — offering a potential alternative to a future dominated by China. An emphasis on hegemony and geopolitics has changed the center of interactions with India in which human rights have been put on the back burner.

Another reason for the issue’s underrepresentation in Western media is academic discrimination. Dr. Al-Zaman furthers, “From my experience, I can say that most of the non-Western regions are treated as less international in global scholarship. It indicates a tendency of academic favoritism, indicating some regions are more international and favorable than other regions. If you search Scopus and Web of Science databases, only 2-5% of misinformation-related publications that dealt with South and South East Asian countries (e.g., India, Myanmar, and Bangladesh) where misinformation leads to massive discrimination, large-scale violence, and killings.” Although fake news causes equal conflict in both Western and non-Western nations, and many cases display even more animosity in the case of the latter, studies regarding non-Western regions are often turned over in favor of those depicting a Western perspective.

Consequently, these issues are diminished and trivialized by others, perpetuating the cycle of the government’s manipulation. Journalists combating fake news have to fight suppression at multiple levels, from systemic to societal, in order to continue informing individuals and furthering their essential work.

In spite of governmental suppression and academic favoritism, many remain hopeful for a better day. Various fact-checkers such as Alt News and Boom have emerged to combat the rise of hyper-politicized sources. The sites’ work focuses on calling out hate speech, taking aim at viral posts that inflame sectarian tensions and spur violent mobs.

But the fight is not just limited to India — university faculty at the Reynolds School of Journalism at the University of Nevada have recently received a grant from the U.S. Consulate General’s Public Affairs Section in Mumbai to create a public diplomacy program to combat large-scale conflicts with misinformation in India. Dr. Paromita Pain, the grant’s leading investigator and an assistant professor of global media, along with Dr. Gi Yun, associate dean at the Reynolds School, and Dr. Sung-Yeon Park, professor at the university’s School of Public Health, develops online training modules to teach journalists and students in West and South India about strategies to counter fake news.

While working on the project, Dr. Pain realized that many students and journalists were keen to learn more about the different ways they can fight the menace of fake news. Thus, she prioritized making this learning accessible to all. Although she recognizes the difficulty of keeping up with the exponential proliferation of misinformation, Dr. Pain states, “the only thing that they [journalists] can do is gradually debunk each item of fake news that they come across via their own social media or by doing stories around it.”

She is eager to further her project, noting, “We have implemented the second round of the program, and we have even more participants than the earlier round that we did. We hope to really extend this training to higher levels.” The researchers are currently working on translating the modules into Hindi, Kannada, Tamil, Gujarati, and other popular languages in India, which are currently short on news-gathering and professional development resources.

Ultimately, Dr. Pain urges people to raise social awareness about the critical issue of fake news, encouraging others to recognize that “Fake news worldwide has become an issue, and we must continue to invest in media education that enables common users like you and me. To understand what news is all about makes us more critical consumers of news, and that is incredibly important.”

As Dr. Al-Zaman states, “No misinformation becomes misinformation unless it has a certain amount of public interest. But when misinformation is connected to issues of tension and fear, it becomes a problem.”

Pritika Patel is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She believes that journalism serves as the vital connection between people and the world...