Pros and Cons in the Transition to Remote Learning Due to COVID-19

We are all just doing the best that we can.

Taylor Chapman ’20, Editorial Columnist, is pictured from earlier in the academic year when school was still in session. “This photo does not accurately represent how I currently look during quarantine, as I wear PJs, sip my coffee, and shoot my computer confused looks,” Chapman said.

Today, I woke up at 11 a.m. I’m not proud of this fact. If I’m being honest, 11 a.m. is pretty early for me nowadays, which is particularly strange considering that I left my house at 6:45 in the morning during the time when I was commuting to Bronx Science. Like me, more than 50 million American students in K-12 are struggling to acclimate to this new, eerie reality of attending class in our living rooms due to the Coronavirus pandemic. In New York City alone, more than 1.1 million students across over 1,700 schools went from commuting to school to learning online, within a week after Mayor DeBlasio closed schools on March 16, 2020. Unsurprisingly, the results of this dramatic, swift change have been mixed.

One of the main challenges presented by remote learning is making sure that students are able to participate in their schooling. When public schools are in session, students need to commute to school in order to have access to teaching in person. But in the case of remote learning, internet access, a computer, and an appropriate learning environment are needed in order to access the teacher virtually, not to mention knowledge of how to type and to use electronics.

In this age of technology, it may seem that these tools are widely accessible, especially in New York City. But in a survey conducted by the NYC DOE, 240,000 families stated they did not have the necessary electronics for their children, and requested devices to assist with distance learning. For Angie DeBoer, a first-grade teacher at Carmen Dragon Elementary in Antioch, California, and Robyn Kramer, a reading specialist at the Stephen Gaynor School in Manhattan, transitioning their students to virtual learning was and continues to be a difficult task.

The Stephen Gaynor School teaches students who have learning differences, ranging from “Attention Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) to speech, language, and reading delays such as dyslexia,” according to their website. “It’s been really challenging because our kids learn through multi-sensory approaches,” Ms. Kramer told me. “We’ve tried to become really creative in order to keep their learning multi-sensory, which isn’t impossible, but it’s definitely harder. It puts a lot of pressure on the parents. I think that the older the kids, the easier it is, but I teach six-year-olds. It’s really disheartening, because they needed these last two months to really solidify their ideas, but they didn’t get the chance to do that.” Mrs. DeBoer agrees. “You can’t give kids what they need in an online environment. You just really can’t.”

But it is not only motivating younger students in a virtual environment that was so challenging, DeBoer said. The entire transition from learning in classrooms to learning virtually has been a game of catch-up from day one. “Because it was such a shock, teachers didn’t have a lot of training. School districts didn’t have any plans about what systems we were going to use. Everything was on the fly,” she said. “Had I been able to train my first graders on these systems, they might have had a better chance, because there’s one program that we’ve been using since the beginning of the year that they can use well.”

Students are feeling the effects of this disorderly transition every day, despite everyone’s best efforts. When the California DOE realized that students needed access to computers to complete their schoolwork, they moved swiftly, collecting laptops from schools, sanitizing them, logging them, and scheduling times where parents could pick up the materials for their children.

“Our district needed to pass out a lot, as a lot of families needed them,” DeBoer told me. “But some families have multiple children, and their children had to share [one computer]. Once they delivered their first round of devices, there were cases where some families could pick up a second one, but I’m sure some couldn’t.” Additionally, many schools are no longer using a standardized method of delivering materials to their classes, which means that students often have to navigate multiple online sites and learn how to keep track of their work, even if they have never used the materials beforehand.

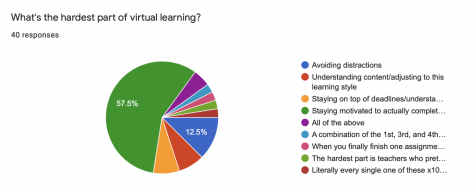

But even with students who have access to their schoolwork, engagement is not guaranteed. I decided to poll my fellow Bronx Science classmates on Instagram, asking if students thought they were really doing 100% of the work their teachers were assigning to them. Of the over 200 responders, 81% said, no. On a Google Form that received 40 responses from a mix of high school and college students, 57.5% said that the hardest part of virtual learning was staying motivated to actually complete their work, while the second most popular pick at 12.5% was avoiding distractions.

A Google Forms auto-generated graph of responses, based on my Instagram survey, indicates that 57.5% of Bronx Science students find that staying motivated through virtual learning is the biggest challenge.

And the distractions are real, particularly for younger students like DeBoer’s. “Sometimes it’s just a couple [students] logging in [to Webex], sometimes it’s six or so,” she said. “Today, we read a little passage about water, and then we wrote about it. One girl was in her bedroom so it would be quiet, but then she didn’t have a desk to write on. Another was at a table, but then it was very loud. A lot of parents are essential workers, so they can’t help with the school work,” she said. “The main thing is that I can’t effectively teach them like I need to. Some of them can’t engage in online learning. It feels sad and frustrating that you can’t give them the learning that they deserve.”

On April 30th, 2020, NYC DOE Chancellor Richard Carranza told New York City principals that there was a “50-50” chance that schools would not open this coming September. Virtual learning has its troubles now, but many teachers are concerned that going into a brand new school year without seeing their students face to face could present new challenges. “Nearing the end of the year, I have a relationship with my students. I know what to ask them, I know how to cater [online learning] to them. But if it was at the beginning of the year, I don’t know how that would be possible,” DeBoer told me.

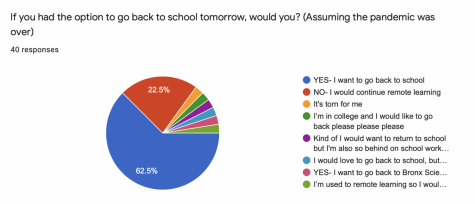

Over 62.5% of respondents to the Google Form that I sent out said that, if they had the option to go back to school safely tomorrow, students would. “As a senior, I want to be able to see my friends again as well as many other teachers and classmates whom I won’t be able to see for a long time,” William Mesnick ’20 said. “Half of the appeal of school is the social aspect, in my opinion, and I feel that a lot of people learn better with others around them…I would rather be in a classroom learning instead. I feel that [virtual learning] has not really been very helpful for actually learning, but it can help with review, which is what most classes would be doing anyway” at this point in the academic year.

A Google Forms auto-generated graph of responses, based on my Instagram survey, indicates that 62.5% of Bronx Science students, the vast majority, would prefer to be back in school.

“My life in college was so different. I was my own person, learning and growing into myself, and now I have been removed from that suddenly and pushed into a space where I have much less privacy,” another responder who wishes to remain anonymous said. “It’s the best that we can do so I’ll take it, but also I cannot wait for it to be over.”

“I feel so unmotivated to do anything without teachers physically being there to enforce schooling,” another anonymous response reads. “For me, it feels kind of like a break, even if it’s not supposed to be. There’s still work, but I feel so much less of a burden on me than when we were in school. But this lack of pressure doesn’t help me to turn in assignments on time. I like remote learning, but it’s not a good way for me to learn effectively.”

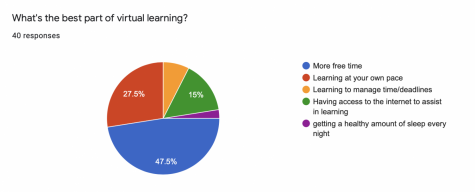

Despite all of the uncertainty, frustration, and mixed emotions, some good things have come out of virtual learning. For instance, 47.5% of the 40 students polled said that the best part of virtual learning was that they have more free time, while 27.5% said that they enjoyed being able to learn at their own pace.

“If I had a choice, I would choose online learning as I can get my work done as fast as within three hours, which I believe is way better than being at school for seven to eight hours,” one anonymous responder said. “I love school, but not for the purpose of learning…Online learning is teaching us in a way that we can work at our own pace and be able to constantly replay our teachers’ lessons.”

Devin Lobsoco ’20 agrees. “Though the workload has been a little heavier since remote learning began, I’ve really been enjoying getting to sleep late and not having to commute. Being able to manage my own deadlines has been pretty easy, and working at my own pace feels great. Above all, not having formal tests is such a stress relief; I never truly realized just how stressed out I was over grades before remote learning began,” he said.

Bronx Science students are not the only Wolverines experiencing the benefits of these changes. Alexander Thorp, the Journalism Advisor and an English teacher at Bronx Science, says that he has been putting his work time to good use. “I have a lot more time for giving detailed feedback on my students’ newspaper articles and my A.P. English Language & Composition students’ weekly homework assignments, which improves their writing and critical thinking skills if they read my detailed comments and use them to improve their next assignments,” Thorp said. Neil Farley, a Physics, Engineering, and Astronomy teacher at Bronx Science, has been keeping busy, too. “[I’ve been doing] a lot of school work during work hours, and spending time with my family, completing yard work, housework, and cleaning, and even helping my wife to cook a little bit. Although she is the best cook, so I want to stay out of the way as much as possible,” Farley said. “[I’ve been listening to] music, reading, connecting with friends, and spending a lot of time with family. I got to spend a lot of time with my daughter who’s back from Germany now, so it’s good to have her back.”

These are tough times for teachers, parents, and students alike, but it is important to remember that we are all doing the best that we can, given that we are living under a global Coronavirus pandemic. I asked Ms. Kramer what she would say to students if she had the opportunity. “I would say, we are right there with you,” Kramer said. “We know that you are doing the best that you can do, and that is enough. I think that’s how we feel, truthfully. Listen, it’s just as hard for all of us, and we are doing the best that we can. At a certain point, you have to be real with yourself.”

A Google Forms auto-generated graph of responses from my Instagram poll indicates that 47.5% of Bronx Science students enjoy having more free time during the remote learning period.

47.5% of the 40 students polled said that the best part of virtual learning was that they have more free time, while 27.5% said that they enjoyed being able to learn at their own pace.

Taylor Chapman is the Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey’ and an Academics Section Reporter for ‘The Observatory.’ The learning experience...