The Unspeakable Horrors of “The World’s Most Friendless People”

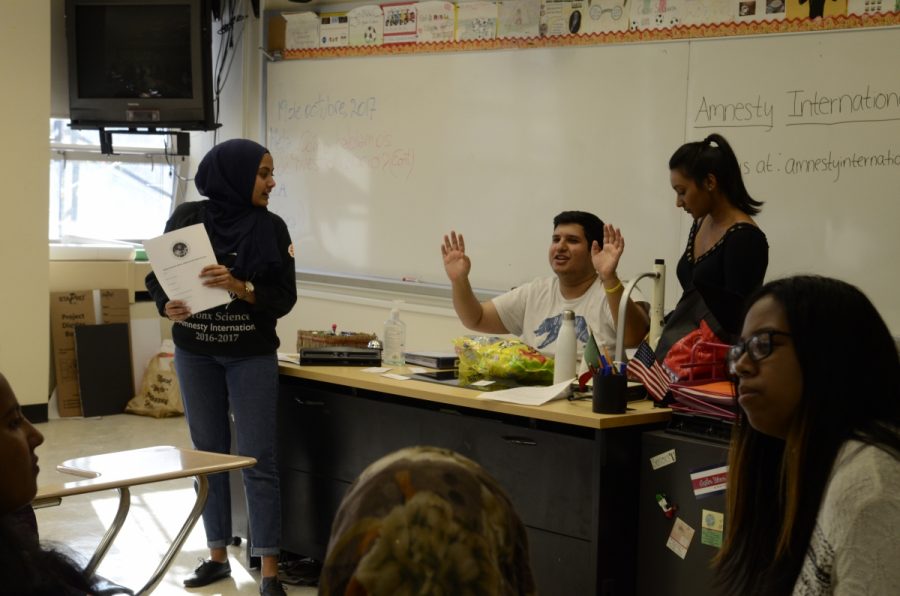

The board of the Amnesty International club shares their thoughts and future plans regarding the Myanmar Genocide.

The United Nations has estimated that nearly 400,000 men, women, and children have fled Myanmar for refuge in Bangladesh. Identified as the country’s minority Muslim population, the Rohingya are rushing to escape persecution by Myanmar’s government.

The minority group is comprised of 1.1 million people, more than a third of whom have already taken refuge in Bangladesh, following recent militant attacks after the Myanmar government crushed them.

In particular, on August 25, 2017, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army staged an attack against security forces in Rakhine, a state in Myanmar. The clash resulted in more than 100 casualties on both sides.

As a result, in September 2017 alone, around 50,000 new refugees arrived in Bangladesh. Approximately 60% of them are children and pregnant women. Many are malnourished and injured, having walked for days in search of sanctuary. The current violence exerted upon the group has been so drastic to the extent that the UN has branded it as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

This issue is not a new one. In fact, the feud between Myanmar’s government and its minority group has a long historical precedent. Before 1989, the nation was once addressed as Burma. The government’s victimization of the Rohingya is rooted in the origins of Burma and a strict, majority Theravada Buddhist tradition.

Unlike typical religions, Theravada Buddhism is very militant. Followers of the faith do not recognize spiritual leaders such as, Dalai Lama, and are not tolerant of other religions they believe would not allow Buddhism to thrive. Hence, the presence of Muslims in Burma threatens the existence of their religion.

Burmese military history also plays a large role in understanding the ways in which the problem initially arose. Before World War Two, Burma was under British imperial rule. During World War Two, when the Japanese invaded Burma, most Theravada Buddhists in Burma supported the Japanese because they believed that they would win the war. The Burmese predicted that the Japanese would be able to drive the British from their motherland.

The Rohingya in Burma, however, remained loyal to the British. Once the British were deemed victorious, the majority of the Burmese population turned against the minority group.

The hate further intensified when the Rohingya were turned into scapegoats by General Ne Win, a military dictator of Burma. After assuming control, Ne Win established a socialist and isolationist regime. In essence, he severed contact with the outside world and transformed Burma into an one-party country by replacing the Parliament with his dictatorship. When he implemented his Communist Manifesto, “The Burmese Road to Socialism,” an economic disaster ensued. Similar to many military dictators in history, he blamed the outcome on the minority, the Rohingya.

Recently, in attempts to bring justice to the issue, the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal has declared Myanmar guilty of genocide against the Rohingya people. The Tribunal is an internationally recognized public opinion board, which functions independently from state authorities. The board engages in sessions which present testimonies that can be later used in international courts, and educates the public on human rights violations. The Tribunal’s possible findings can be used as the basis for international bodies, such as the International Criminal Court and other super-powers, to act.

However, another problem should be called to attention. As the public takes action, Nobel Prize winner and Burmese politician Aung San Suu Kyi has remained idle in this situation, and her spokespersons also have mocked the supposed “fabricated news” about the plight of the Rohingya. Numerous diplomats have dismissed the accusations made. This has caused a lot of controversy, and as a result, her lack of action has caused several people throughout the world to advocate for revoking her Nobel Peace Prize.

In spite of this, the Bronx Science community has remained very involved in international affairs. The student body has generated multiple propositions regarding the possible solutions that can be done to resolve the conflict. President of the school’s Amnesty International club, Nusrath Jahan ’18 suggests that first world countries must allow refugees from Myanmar to cross their borders. “Many countries, including the United States, Thailand, and Australia, have adequate resources to support an influx of refugees into their country,” said Jahan.

The government is abusing their power, costing the lives of thousands of Rohingya.

In addition, Jahan believes that first world countries should fund countries such as Bangladesh that are accepting refugees. “About 430,000 Rohingya have arrived in Bangladesh in a month without any documents, and they are being forced to wait for days before receiving any sort of verification of the legality,” she stated. “We can also donate to the Rohingya refugees in Myanmar and Bangladesh through the International Rescue Committee (IRC), which would provide many families with water, food, protection, and health care.”

Marry Lim ’17 is a Burmese Bronx Science alumni who suggests that the genocide can only come to an end through solely focusing on the inner workings of the government. “There’s a lack of transparency on the genocide within Myanmar. Since journalism as a whole is frowned upon in the country, there are very limited news outlets available,” said Lim. She explains that “no matter how much research has been thrown at Myanmar from the UN or Amnesty International, nothing can be done until the people and the government within the country recognize the genocide and make amends with the minority.”

On the other hand, Jahan recommends that the best way to handle the fault of the government is by overthrowing it. “The government is abusing their power, costing the lives of thousands of Rohingya. The United Nations (UN) must continue to urge Myanmar officials to end military operations and restore their state.”

Although Marry and Nusrath have different proposals of solutions to help relieve and reverse the effects of the genocide, both point towards changing the government for better and fighting for freedom and liberty of the oppressed minority of the Rohingya.

Even though genocide has been a recurring event throughout history, which foreshadows countless casualties and heightens cultural tensions, it can also serve as a reminder to prevent other countries from committing such atrocities. The detriment of genocide can be reduced, beginning from small-scale endeavors occurring within a single community to large-scale global efforts of huge organizations. For example, to raise awareness about the issue, Jahan’s club prepared a simulation that mimicked the hardships endured by the minority.

President of Amnesty International, Nusrath Jahan ’18 explains the simulation that mimicked the hardships endured by the minority.

Club members of Amnesty International attempt to put themselves in the shoes of the Rohingya Minority.

Maliha Akter is a Senior Staff Reporter for ‘The Science Survey’ and the Copy Chief for ‘The Observatory.’ She enjoys journalistic writing because...

Stephanie Weng is an Online Editor for ‘The Science Survey’ and a Group Section Reporter for ‘The Observatory.’ Journalism is a passion that she...