Bronx Science is filled with future scientists (maybe even some future Nobel laureates), lawyers, bankers, social justice activists, businesspeople, and an infinite number of others destined for impactful careers.

A group of students wondered: how much time do all these future world leaders spend passively listening at Bronx Science rather than thinking critically and solving problems? They decided to find out.

In ten classrooms, the students started a stopwatch every time the teacher spoke and paused every time they stopped. It turns out, on average, the time teachers spent talking was roughly 19 minutes out of 42.

Depending on how you look at it, that’s a lot of time or very little. It’s perhaps not as much time as the students would have guessed. On the other hand, it means that in most classrooms our future leaders spend roughly half of each class – half of the day and half of the whole year – sitting patiently (almost always passively) and taking in information. It seems that really understanding how students are being engaged requires further study.

One way to go deeper is to learn from the classrooms where students feel most engaged.

I surveyed fifty sophomores and asked them them to identify one to three teachers whose classes fit a set of criteria; they are places where students learn new things every day, the teachers use most of the forty-four minute class period in order to engage students in doing work, and the classes are so enjoyable that if they went on for an extra ten minutes, students wouldn’t notice.

Most students took at least a minute to think, often saying things like, “That’s a hard question,” and most students did not appear very confident in their answers. The two names that repeatedly popped up, however, were Mr. Porfirio Gonzowitz, a Bronx Science Social Studies teacher, and Ms. Sophia Sapozhnikov, a Bronx Science English teacher. Students who shared these views almost always responded within an instant and insisted these teachers should be featured.

After visiting both classrooms, I found that neither environment checked every tidy box that I had made in my mind when I thought through what I expected to see.

What I discovered was that the culture of both classrooms fostered student engagement, and it wasn’t entirely the result of how long the teachers spent talking.

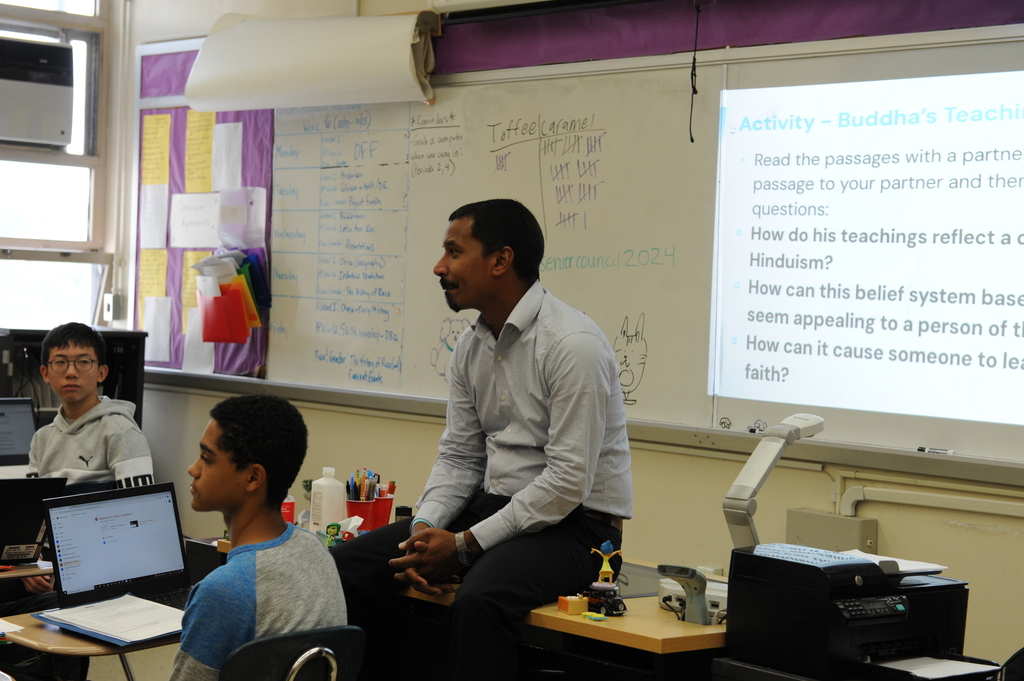

In Mr. Gonzowitz’ class, I was struck by how long he stuck with questions. If students didn’t immediately get the answer, he would wait, while most teachers in my experience would move on and give the answer for the sake of time.

I knew from the moment that I walked into Mr. Gonzowitz’ room that he made every student there feel seen. At one point, he posed a question to the class, “What’s the last thing the Aryans brought to India?” No one answered and he swung his head around from left to right, asking, “No one?” I knew the answer, but I wasn’t planning on sharing it. But somehow, he knew that I knew. He called on me.

Still puzzling over how he knew, I stopped by his SGI to get to know him better. “I remember every single one of my students. I remember every single one of the things that they did in my class for the most part. Everybody has a mark in my mind, for me. That’s what I love about teaching,” he said.

Talking to Mr. Gonzowitz, I realized that what made me feel seen in his class had everything to do with how he views his purpose as a teacher. He said, “I think that the biggest challenge for me [in teaching] is making sure [students] are heard. [Students] are trying to find people who can hear [them].”

The result is a classroom where students want to be. When I asked one of his former students, Siena Ruske ’26, to tell me about Mr. Gonzowitz, she immediately responded, “He makes the class feel like a community…there were so many inside jokes in our class.”

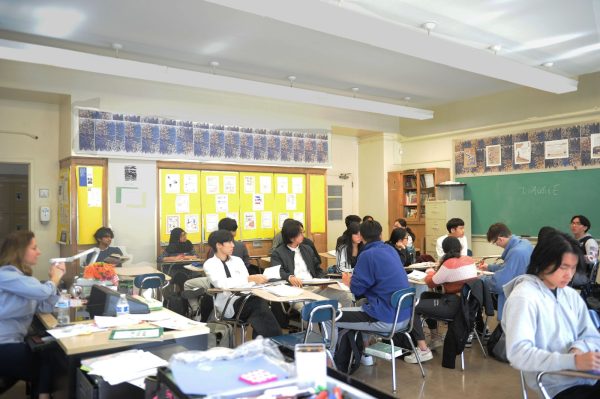

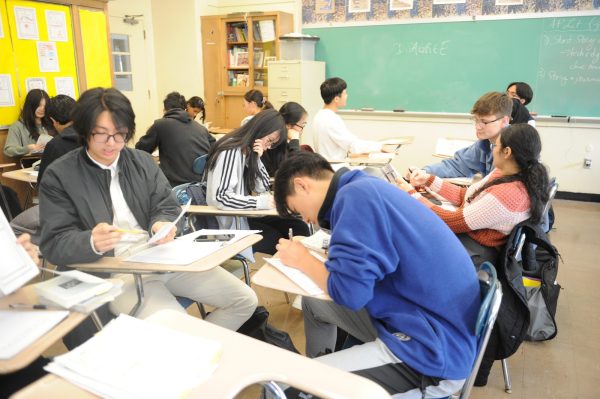

In Ms. Sapozhnikov’s class, the atmosphere was intellectually engaging. The day that I visited, there was a lively discussion on how technology impacts our communication and lifestyle today. Each conversation started with a statement, one of which was, “Communication via e-mail, text, or social media is just as real as face-to-face communication.” Students sorted themselves into four corners to represent a viewpoint on the topic (strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree). Students from each corner were eager to share their opinions and start a debate.

The conversation was impassioned because Ms. Sapozhnikov chose a topic that mattered to the students’ lives. The class took place the day before the students were going to start reading Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, a book that describes a society in which people are completely absorbed in technology and uninterested in authentic communication. Listening to the class argue over what the purpose of our education is and what it should be reminded me of how much the novel had made me think critically about my life, and it made me want to reread the book.

I wondered why she used her English class for a discussion that seemed only tangentially related to the material.

Remembering how important Mr. Gonzowitz’ sense of his purpose as a teacher seemed to be to his teaching approach, I asked Ms. Sapozhnikov what she viewed as her purpose in the classroom. She described her role as trying to inspire students because, “you have all these resources where you students can basically learn whatever it is you want. You just need to have the discipline and the drive in order to do so.”

I gained an even deeper sense of how she views her role as a teacher when she told me about a myth that influenced how she thinks about teaching.

She said, “The myth is that, before a baby is born, it actually learns everything that it’s supposed to know in the world, and then, right before it enters the world, an angel slaps it over here,” she pointed to above her lip, “and the baby forgets everything. As you grow up, you’re actually learning everything you were meant to know right before you were born. It’s a very strange story, but I believe that it shows us that whatever we need to learn, we have inside of us and somebody somehow needs to bring that out.”

After visiting both classrooms and talking to these two teachers and their students, I found that what fosters student engagement is more about the purpose and mindsets of a teacher rather than the particular instructional choices they might make.

The result of how these teachers see their role and their students is that students want to be in the classrooms and they want to engage.

When a student walks into Mr. Gonzowitz’s classroom, they know, ‘I matter.’ When a student walks into Ms. Sapozhnikov’s classroom, they know ‘this matters.’

Perhaps because of this, neither of these teachers saw controlling the classroom as a necessity, perhaps another reason students like being in these classrooms.

Gonzowitz does not tell students to put their phones away, rarely asks them to stop talking and listen up, and trusts that the students will make the most responsible choice become engaged with the interesting material of the class. Ms. Sapozhnikov lets students discuss the material amongst themselves at any point in the class, rarely requesting silence, or putting all attention upon herself.

“One of the bigger issues that I see with the field of education is that too many teachers want to hold onto control,” Mr. Gonzowitz said. “They hold onto it as if the teacher has to be in control, the teacher has to dictate terms, and I think that there is such a great push now that the power balance is shifting.”

When a student walks into Mr. Gonzowitz’s classroom, they know, ‘I matter.’ When a student walks into Ms. Sapozhnikov’s classroom, they know ‘this matters.’