From Stream to Tap: The Inner Workings of the New York Water System

Due to the widespread accessibility of liquid in New York, many people consistently overlook the importance of our water system. Here, we take a closer look at one of the country’s most impressive and widespread industrial structures.

Very few institutions have stood the test of time as well as the New York Water System. Although often undercut, it has consistently provided fresh water to over 9.5 million Americans for centuries; it holds a history of protest, population growth, and hardship that many people are unaware of.

The story begins in 18th century New York, where a mushrooming population was quickly outgrowing New York’s scarce amount of water. Under the cover of constant gunfire and in the midst of revolution, the city experienced its first water shortage, deeply affecting its 22,000 residents. At the same time, disease began to plague the existing water; ships docking in New York ports began to pack water for the voyage home as well, fearful to fill it up in the city’s harmful taps.

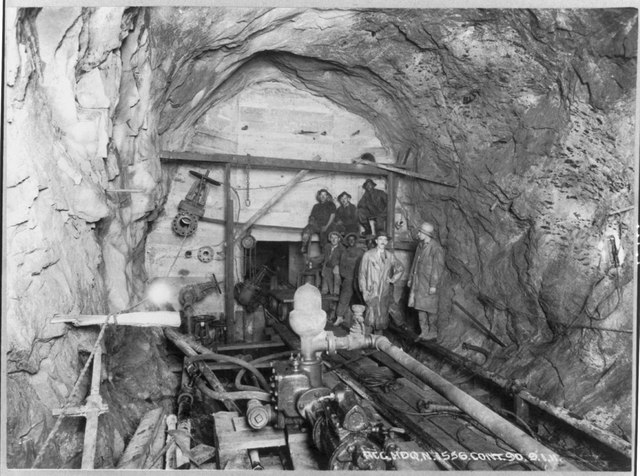

The crisis pushed city officials to build over 40 miles of wooden piping by 1830. Yet it still wasn’t enough, nearly 200,000 New Yorkers lived in the city, yet this innovative infrastructure still only served 60,000, primarily composed of the upper echelon of residents. A culmination of these issues finally pressed the city government to construct a dam and an aqueduct on the Croton River, known today as Old Croton Aqueduct, which now serves as the unofficial birthplace of New York’s modern water system.

However, as the system continued to expand and reform, the pristine counties of Dutchess and Columbia that make up the Catskill region needed to be tapped. Built in 1915, the Catskill aqueduct crosses the river between Storm King and West Point Academy and dips under sea level to pass the base of Bear Mountain, molding and disrupting the landscape all the way to its destination.

This expansionist view was often controversial; upstate communities whose land and resources were used to quench New Yorker’s never-ending thirst were given no say in these decisions. The city seized any water resources it could get its hands on, and often did not compensate the owners fairly.

This was part of the ongoing clash pitting the ideas of conservation against those of expansion. Water sources like the Hudson River were never considered as potential water providers, and the notion of conservation wasn’t seriously entertained by governments until the 1980s. Instead, the city argued that the liquid was too far gone, and that the untapped resources upstate were uniquely needed instead, despite the consequence.

These early aqueducts developed into the sprawling, modern system in place today. The Catskill lines alone encompass more than a million acres of land and are considered today to be a modern engineering marvel.

Although now one can simply turn on the faucet and expect gushing, purified water at their fingertips, many fail to recognize the expansive process their liquid undergoes to reach them.

It can take anywhere from 12 weeks to up to a year for your water to find its way to the city through the vast expanse of reservoirs, tunnels, dams and streams that stretch across the state, developed for the sole purpose of providing fresh water to city residents.

First, your water is tapped from the 92 mile Catskill aqueduct which expands all across upstate New York and feeds the liquid into the Kensico River. Waiting there are robotic buoys, ready to transmit information about your water’s quality to a complex centralized computer system. Field scientists also remain on hand to monitor the liquids temperature, microbial contents, nutrient levels, and PH levels.

From the data collected, analysts can predict the quality and quantity of the water that day, and even for months into the future. In particular, Department of Environmental Protection officials look out for signs of turbidity, or cloudiness in the water, caused by constant heavy rains and winds which can shift silt into the water and disrupt the treatment.

Next, your water has to pass through the world’s largest disinfectant treatment facility, located in Westchester county. There, a system of pipes slows the liquid before it gets offset with ultraviolet radiation and treated with chlorine to prevent harmful byproducts in the water.

The last stop is the Hillview Reservoir, which acts like a giant bathtub, if only your bathtub could hold 900 gallons of water. There, sodium hydroxide, phosphoric acid and chlorine are added to disinfect and prevent toxins from getting into your water while three drain-like tunnels wait to propel water downhill with enough gravity to reach New York City homes and apartment buildings.

Before being distributed to city apartments, the water quality is tested at over 1,000 sampling stations around the city. This is a last check to make sure that your water tastes normal and is safe to consume.

Finally, the water reaches your home! If you live in a building less than 6 stories tall, gravity will step in and propel the water up to your pipes. If not, pumps in your building help to move the liquid up to the upper floors. Either way, a months-long journey comes to a close and water is safely delivered to your taps.

The squeak of the faucet and subsequent flow of freshwater is a mundane picture to some, a dull snapshot amongst the more vibrant pieces of daily life. We have become used to this image, to the expectation that when we twist the kitchen faucet, clean, drinkable water will gush out. But for many, this is not the case.

Currently, an approximate 2.3 billion people around the world live in water stressed nations. Countries including Lebanon, where more than 70% of people experience water shortages, Pakistan, which is estimated to reach complete water scarcity by 2025, and Syria, which is plagued seasonally with debilitating droughts, represent just a few of the countries torn apart due to water concerns.

This issue is not limited to foreign nations; it is an alarming issue within our own states and communities. Notable American cities like Houston, Flint, Baltimore and Las Vegas have all experienced significant shortages with their water, with many relying on pre-packaged water for months at a time in order to supply their citizens with fresh water.

This issue is not just applicable to cities as well, but is a big problem on Native American reservations, which often experience huge water shortages due to water from their rivers and streams being siphoned off to nearby cities. Yet even with these close to home concerns, many New Yorkers consistently overlook and antagonize our New York water institutions.

With that in mind, take a second as you turn on the faucet to appreciate the liquid gushing out. The New York City Water System is our history; winding, messy, expansive, and in need of reform, but very remarkable.

The squeak of the faucet and subsequent flow of freshwater is a mundane picture to some, a dull snapshot amongst the more vibrant pieces of daily life. We have become used to this image, to the expectation that when we twist the kitchen faucet, clean, drinkable water will gush out.

Allegra Lief is a Copy Chief for The Science Survey and is responsible for the review and revision of her peers' articles prior to publication. Through...