The American Museum of Natural History: A Behind the Scenes Look At the Largest Fossil Collection In the World

Located on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, the museum reveals to us the lives of fossils millions of years after they first roamed the earth.

The American Museum of Natural History’s paleontology team is shown digging for fossils on their 2022 trip to Mongolia’s Gobi Desert.

Eighty million years ago, present-day Mongolia’s Gobi Desert was a dinosaur’s paradise. Today, with its soaring valleys, beating sun, and sand dunes as far as the eye can see, the magnificent desert remains a magical place. However, during the Cretaceous Period (145 to 66 million years ago), when dinosaurs roamed the area, the Gobi was a humid, warm climate, covered by dense conifer forests and streams. Here, the velociraptors stalked their prey, their razor sharp claws glinting in the sunlight. The Tarbosaurus, a rare cousin of Tyrannosaurus rex let out a mighty roar, sending shivers down the spines of nearby prey and targets. Gentle giants like the long necked, plant eating Titanosaur also called these sands home, their massive bodies living in harmony with the smaller, more agile species. It was a scene of endless wonder and imagination.

Despite the beauty of this landscape, the frequent avalanche-like sand slides were the cause of mass deaths, encasing dinosaurs in sand and preserving their remains for millennia through the process of fossilization.

Today, interest in these remains is rising once again. Paleontologists from all over the world are traveling to Mongolia for the opportunity to excavate some of the most diverse fossils found across the globe. Among the multitude of museums and research facilities that send paleontologists to the Gobi, one establishment stands out, The American Museum of Natural History, right here in New York City.

The American Museum of Natural History, otherwise known as AMNH, is located on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The museum houses over thirty-four million specimens, displayed and stored throughout the museum’s twenty four buildings. They house some of the world’s greatest collections of dinosaur fossils collected through excavation trips around the globe, including Patagonia and Romania. One of the longest running fossil expeditions, as well as the most well known among dinosaur enthusiasts is the three week Gobi expedition in southern Mongolia. Though the trip may come with the prestige of being selected, not just any staff member is up for the challenge. The journey includes grueling weeks of living off of canned food, sleeping in tents, encountering extreme weather, and completing endless walkabouts, with unfortunately, no showers available — all in the hopes of discovering the fossil that could come with a discovery, changing the world as we know it.

Excavations

Carolyn Merrill, a research assistant in AMNH’s Department of Vertebrate Paleontology, is one of the lucky few selected for this annual trip to the Gobi Desert, and has been traveling to the site for the past two decades. However, this was not her first AMMH expedition. Merill described her first trip fondly, yet with a hint of its obstacles, as the “hardest trip (she) has ever done in her life.”

Merrill was first sent on a last minute expedition to Patagonia, a geographical region in South America, filled with vast forest, natural reserves, national parks, glaciers and native wildlife. On this trip, she and a singular partner faced treacherous winds, threatening sinkholes, and perilous cliffs. When describing some of these locations, Merrill said, “One of the days was on the coast where the wind was so bad we were falling down as we tried to walk.” Merrill chuckled as she added, “It certainly was anything but boring.”

When she was finally chosen to join the Mongolia expedition, Merrill found herself preparing for very different yet equally challenging conditions. Several weeks before the expedition, the paleontologists began to collect canned foods and bottles of water to bring with them, facing a lack of food or resources once in the desert. Once they arrive, all of their food has to be cooked in a wok, and they doze off under the stars. That is, unless the weather dictates otherwise — in which case they find themselves seeking shelter from rain under their trucks.

Days start early for the paleontologists. They are out by sunrise, surveying and searching for localities that may hold the next big discovery. Merrill discusses the surplus of fossils that are found, making the Gobi a favorite amongst the team. “We find stuff everywhere there; fully articulated dinosaurs, egg nests, embryos, and early mammals. It truly is a fossil paradise.”

A “fossil paradise” is definitely the way to describe it. Given the unique and special conditions of the Gobi, particularly during the time of dinosaurs, the preservation of the fossils is unlike anywhere else. Despite the arid climate of the Gobi now, the region has only been a desert for the past 30 million years. Before that, it was a lush, tropical area home to a wide variety of plants and animals. However, as millennia passed and global temperatures fell, the once luscious environment became much drier, and the plants and animals that once inhabited the desert became trapped in sediment.

The formation of rocks in the Gobi are exposed through wind and erosion, meaning that they are not covered by soil, making the fossils much easier to find than many other excavation sites. While fossils are relatively easy to find in the Gobi, the key is to find something that has never been found before. With the millions of artifacts in the museum’s collections already, there is a lot that has already been covered and confirmed in various fields, so Merrill and her team are looking for new, unique fossils of all sizes to add to their collections. Smaller fossils are much more common and relatively easy to excavate, pack, and ship back to the United States. This story differs from larger bones that, while being more rare, are also much more complex to transfer.

Transportation

Fossilization replaces original bone and organic material with minerals and stone, meaning that fossils can be incredibly heavy. Full dinosaur skeletons can weigh anywhere from hundreds to thousands of pounds. In the case of the quite complex, often exceedingly fragile Gobi specimens, it’s a long trip to New York City where they will be prepared and researched in collaboration with colleagues from Mongolia.

This task of safe transport is far from simple. When paleontologists discover and choose to excavate a fossil, the first thing they need to do is figure out how to dig it out safely and quickly.

Once the bones are exposed and their boundaries identified, they must be quickly encased in plaster, either in sections, or as full skeletons. Despite bones belonging to some of the largest land mammals, they can be extremely delicate, especially after spending millions of years compacted under pressure underground. A lot of the time, the fossils are so fragile that AMNH paleontologists need to excavate the specimen along with its surrounding matrix as a block. The plaster provides extra support, while the paleontologists begin the next step of packing them up.

To ensure that the fossils get back to the labs as safely and quickly as possible, the scientists must hurry to complete their preparation. A group of them will go to the local markets and find the materials to create wood crates from scratch, a crucial step of packaging fossils on the larger end. These crates are placed on trains that transport them to China, which gets on a ship, then another train, finally landing them in New York City.

Collection Management and Research

Even though the fossils do not stay in New York permanently and are eventually returned to Mongolia, scientists at AMNH are sure to make the most of the time that they have. Fossils are primarily categorized based on their age, size, and overall characteristics. They are given a unique identifying number through the process of cataloging.

Chris Norris, former director of Paleontology Collections at AMNH for over fifteen years, describes the biggest challenge he faced in the role of attempting to organize and gather information. Regarding both fossils that have arrived at the museum recently as loans, as well as those that have been in storage for years, there is frequently a lack of information regarding many of the specimens. Digging out this information requires a deep dive into museum archives and a complex understanding of what the collections hold.

“A lot of human history is written down. For the natural world, such as what happened on Earth 35 million years ago, there is no record other than natural history collections,” said Norris. “This is why we spend all of this time and all of these resources working to understand something that may or may not be a turning point in history, because until we do, we simply do not know.” With all of this effort, the question ultimately arises: What is the bigger picture?

Dr. Norris points out the simple answer: it is important evidence of evolution and how wildlife used to respond to their environments. Yet, he goes even further: “Yes, without them we would have a great deal of difficulty understanding what happened in the past and why we are here today. But more importantly, we do all this work to be able to predict what may happen on our planet in the future.”

The key idea here is change. According to Norris, many people see the planet as a static environment that remains the same throughout history. In present times, a key concern relating to this is the increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. While this issue may seem like it is unprecedented, it is actually strongly related to the work done in paleontology. In reality, the planet can change for a multitude of reasons, and humans can be one of those reasons. It is fairly simple to get an idea of what could happen to our planet based on assumptions made about Earth now, but if you go back in time to when planet temperatures rose in the past, the depiction can provide a fairly accurate story.

Fifty five million years ago, an era called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum took place, where the entire planet faced an extreme greenhouse climate and a great deal of heat was trapped in the atmosphere. Why does this relate to fossils? The specimens found from this time period can say a lot, from rainfall patterns, vegetation, animal size, and even the responses of microscopic organisms. Overall, we can predict patterns of what we are facing now, in a similar situation. Is this how our wildlife is going to respond in the future? Should we be preparing based on the conclusions paleontologists have come to?

Creating a Story

Of the millions of collections at the American Museum of Natural History, only about 2% of specimens are on public display. Anyone organizing an exhibition hall must decide what they want their viewers to take away, and that main idea is usually focused around this idea of change through evolution. In fossil halls, change can either be rapid or can slowly take place over millennia. In both cases, it is quite profound.

With decades of experience creating fossil halls under his belt, Norris emphasizes the importance of creating a story with his exhibitions. He recognizes the intense auditory and visual experiences of being in a museum gallery, especially one catered to families (kids pulling on your arm, people screaming and taking pictures), and he makes sure that the information that needs to be conveyed is done so quickly. The cases that make up a typical gallery naturally show specimens that are interesting to look at, but they will also include brief pieces of text that explain their importance.

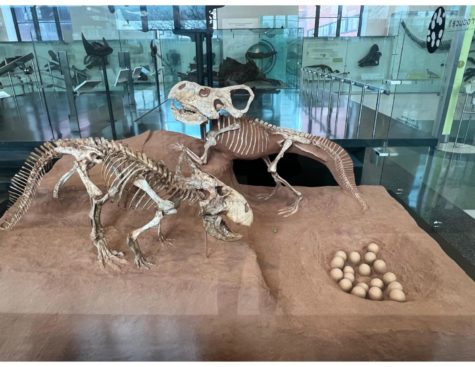

When a visitor is examining the Nesting Oviraptor, a cast of one of the most famous Gobi fossils, displayed in the AMNH fossil halls, they might walk away with only the image of a small jumble of bones and several sphere-shaped rocks. Yet with the right exhibition, they can also leave knowing that this jumble of bones are actually the fossils of an oviraptor that lived 75 million years ago, and that the oviraptor was not an egg thief, as its name might suggest, but instead a bird-like dinosaur working to protect its eggs during a violent sandstorm. They will leave having seen evidence of some of the earliest social, protective behavior ever discovered.

Over his decades of experience developing museum exhibitions, Norris has learned that there must be a perfect balance between beauty and information.“They have to look pretty. People will look at it and say ‘Oh that’s beautiful,’ but at the same time, under the surface, we are telling people to look at what really should be taken away.”

Almost everyone learns about dinosaurs as children. We learn about the power of these ancient, mysterious creatures; maybe you even dressed up as one for Halloween. Whatever the experience may be, the key word usually associated is “ancient.” Yet the American Museum of Natural History eradicates this viewpoint. The teams at the museum truly bring these timeless fossils back to life, and when visitors from all around the world come to see this for themselves, the message is clear to all.

To plan your visit to the Museum of Natural History, click HERE for all information.

“A lot of human history is written down. For the natural world, such as what happened on Earth 35 million years ago, there is no record other than natural history collections,” said Norris. “This is why we spend all of this time and all of these resources working to understand something that may or may not be a turning point in history, because until we do, we simply do not know.”

Claire Elkin is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She believes in the power of journalism and how it can shed light on topics and issues that...