Are students unhappy and anxious because they haven’t been taught to cope with 21st century lives, or do our 21st century lives need changing?

According to the American Psychological Association, in the ten years before the Coronavirus pandemic, persistent hopelessness, sadness, and negative behaviors all increased by about 40% among young people. Among Gen Z, there is wide recognition that if you are struggling with mental health, you should get help from a professional and there is no shame in taking medication or talking openly about your struggles. Even for people who struggle less with mental health, everyone understands the importance of little rituals to keep us going or taking a mental health day if necessary. Educators and legislators are looking for solutions; Mayor Eric Adams recently instituted a requirement for mindful breathing in NYC public schools.

But the rising rates of anxiety and depression among teens aren’t going to be solved by fostering awareness or taking ‘me time.’

The mental health epidemic is a nationwide crisis, and addressing the problem with individual-level solutions won’t work. We can’t explain the recent rise in mental health issues and feelings of hopelessness with individual causes; everyone did not coincidentally get stressed and hopeless all at the same time.

“If someone is driving through a crowd, running people over, the smart move is not to declare an epidemic of people suffering from ‘Got Run Over by a Car Syndrome’ and go searching for the underlying biological mechanism that must be causing it,” wrote Danielle Carr, who is an Assistant Professor at the Institute for Society and Genetics at UCLA. “You have to treat the very real suffering that is happening in the bodies of the people affected, obviously, but the key point is this: You’re going to have to stop the guy running over people with the car.”

We are accustomed to understanding mental illness through a biological lens — but we often overlook the most obvious conditions of our lives that drive misery. Adolescents all over the world are suffering from a lack of purpose, meaning, and community. It’s driving unprecedented rates of hopelessness and sadness in youth, and teenagers are searching in their past for what could be causing these feelings and looking for methods to cope. But this isn’t a problem that is solved by everyone individually coping. Instead, our lives need to change.

“If you’re feeling anxious, it could also be a sign that something in your life is not working, and there may be a need for change,” wrote journalist Hannah Seo in her New York Times article ‘Small Steps to Improve Your Mental Health in 2023. But students are trapped in lives they have no power to change. They are forced to go to schools where every day is the same. They are offered no choice in how they learn. If students are unhappy with their lives, they don’t have the power to create the life they want. Students go to schools tailored for only a few types of learners and can’t choose to grow their knowledge and skills on their own terms.

“School is so repetitive, and I have always thought that,” said Lindsay Sander ’26. “It’s almost like you are a guinea pig running in a wheel. It’s the same day over and over again. You go to bed thinking, ‘oh well now I have the next day.’”

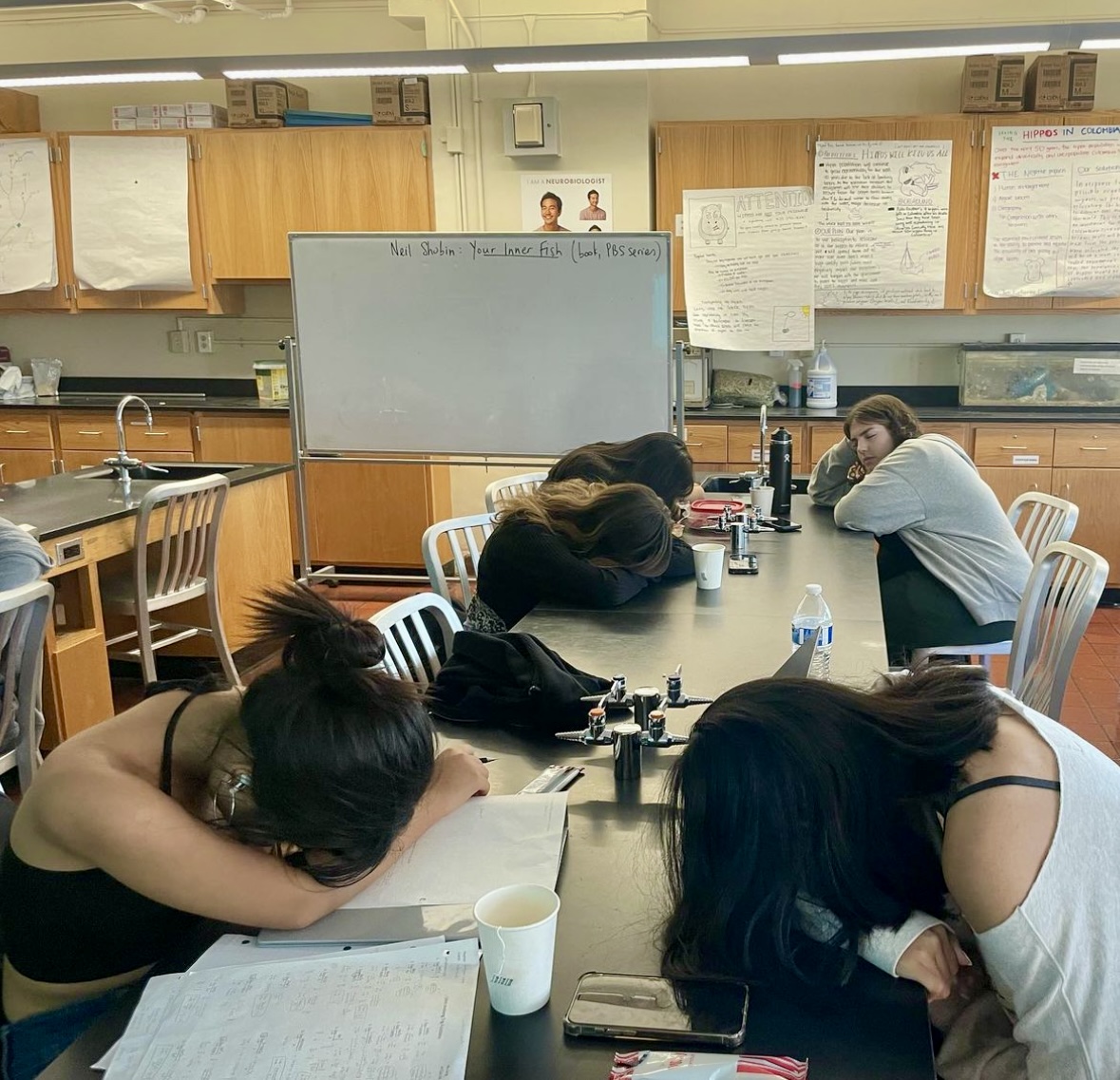

School creates an environment completely closed off from the real world, and so different from it. Outside of the walls of a school, police brutality, climate change, and global war may ravage the world and new political crises could arise at any moment, but inside these walls, our days remain unchanged. We stay in the constant repetition of worksheets, lessons, and tests.

Changing the day-to-day lives of students means changing classrooms. “While complying can be an effective strategy for physical survival, it’s a lousy one for personal fulfillment,” in the words of researcher Daniel Pink. “Living a satisfying life requires more than simply meeting the demands of those in control. Yet in our offices and our classrooms we have way too much compliance and way too little engagement.” Pink continued, “The former might get you through the day, but only the latter will get you through the night.” Our education dominates our lives – and that means so much of students’ time is spent on what adults alone deem useful without the input of students. Kids, like adults, desire independence and autonomy. It shouldn’t be shocking that if most students’ lives are dominated by the demands of teachers, parents, or the pressure to get into a good college, they will feel purposeless.

In the same vein that adults tell us how to spend our time, teachers are imploring us to spend less time on social media. Everybody’s worried about our generation’s attention span. There’s nothing more ironic than listening to a teacher telling us we need to control our attention when they tell us what to do every day.

We can’t expect this generation to claim their attention if we aren’t teaching them to make their own choices in school. It shouldn’t be surprising that if students have every choice already made for them about when and what they will study, they will have trouble controlling their attention. The solution to dwindling attention spans is not self-discipline or focusing exercises, but rather giving students the choice to study and do what they care about.

But as students, we aren’t yet trusted to make our own decisions. The education system is built on the idea that to have a rigorous education, days for the first 18 years of our lives should be structured for students instead of by students. Almost every moment of every day is planned, with worksheets, lessons, and turn-and-talks prepared for us. Our right to free will has been taken away from us because we aren’t considered capable of making rational, intelligent, and moral decisions — we aren’t considered whole human beings yet.

“Schools are places of certainty, run by churches and people who want to install certain content,” said Elliot Washor, a co-founder of a progressive school that places students in internships, “But the world is uncertain. The world is alive and dynamic.”

In chemistry classes, we often do tedious unit conversions. In math classes, we may do long problems riddled with opportunities for arithmetic mistakes. In English classes, students often read texts that seem disconnected from their lives, and seem to offer little wisdom or practical skills to gain. In so many instances, it’s unclear how the material is furthering our knowledge or skills. It seems meaningless in comparison to the world problems confronting us, and futile in developing us as future leaders.

“In school there’s always a right answer, but with solving real problems, there isn’t a right answer,” said Sonali Campbell ’26. “By teaching people that there is a right answer, that’s going to teach you to believe that there always is one right answer in the future. But, if we were taught that there isn’t always a right answer, then we enter a world in which we can’t really be sure of anything. There’s a line between being open to accepting there are other possible right answers and believing we live in a world with no hope and no direction.”

Campbell expressed one of the reasons why the education system is so hard to change. School assures students their lives are on the right track as long as they get good grades and do extracurriculars. It assigns daily tasks that students can be satisfied upon completing. It paints a picture of our future that’s neat and tidy. We create schools to reflect what we wish the world would look like: predictable and black-and-white. Giving that up is hard.

Although the years we spend studying in school are “stressful, anxiety-inducing, and depression-inducing” as Campbell reflects, students look at their education from a long-term perspective, and ask the question: will our education bring us lifelong skills?

“You’re not graded in the real world.” Campbell reflected, “You’re not tested. That’s a big part of school that isn’t a big part of the real world.”

Murmuration, an organization that advocates for education reform, found that at the beginning of the 2022-2023 school year, a third of Generation Z surveyed believed their schools didn’t listen to their voices. Only 2 in 5 of Generation Z surveyed said their K-12 education prepared them to succeed in their careers. Only 37% believed it prepared them to be active engaged citizens, and only 31% believed it prepared them to live a balanced and happy life.

In our K-12 education, it’s estimated that we spend 15,000 hours in school. This doesn’t include the time we spend on homework or extracurriculars. For such an immense commitment, students should be sure that they are leaving with life-long skills that prepare them to navigate the world and shape a better future.

“If you are always thinking I need to do this, so I can do this, and get into a good college, I don’t think that that is going to be effective in policymaking,” said Maddy Moser ’26. “If you are just like, ‘Oh I need to do this so I can do that,’ you need to take off those blinders and think about the entire world around you. After college, then what? It’s good to have goals, but if you can’t think beyond those goals it’s not going to be an effective way to prepare yourself for the real world and make real world change.”

Maria Montessori, an Italian physician and educator, created a new teaching style on the premise that students are intrinsically-motivated to learn. Montessori schools across the United States use her ideas. She described traditional schools as a place “where the children are repressed in the spontaneous expression of their personality till they are almost like dead beings.”

She used an analogy to explain the flaws of education. Montessori explained that if a scientist is invited to study insects at a university, and you give him dead butterflies with their wings spread out, he can’t accomplish much. She explained that a teacher in a school is put in the same predicament. She said, “In…school, the children, like butterflies mounted on pins, are fastened each to his place, the desk, spreading the useless wings of barren and meaningless knowledge which they have acquired.”

When students aren’t offered choices in how and what they learn, teachers resort to incentivizing them with rewards and punishments. Montessori offered a scathing critique of the motivators most educators use. She described “Such prizes and punishments are … the bench of the soul, the instrument of slavery for the spirit.”

Frances Auth ‘26 reflected on the impact of these motivators. “There’s always something hanging over our heads. I’m thinking, ‘If you don’t do this you can’t get into college, if you don’t do this you can’t pass the A.P. test.’ Those motivators held over our heads are really exhausting, because I have to pass this upcoming test but also I’m thinking about the SATs.”

Schools around the world are not the only cause of this mental crisis, but they can be part of the solution that brings hope to young people’s lives. If we want our generation and all future generations to be happy, capable leaders, we need to not just reform our school system but completely change it.

The division between school and the real world means we put energy into work that can feel meaningless. School is a game we play for academic validation at the expense of joy and real world skills. In school, teachers tell us what the problem is we need to solve and how to solve it. In the real world, the problems and solutions aren’t always obvious. Our society has justified the time and energy we put into school rather than asking ourselves whether all the work is worth it.

Of course, school often develops problems-solving skills, analytical thinking, discipline, and drive that we can use for the rest of our lives. But schools should take an approach that allows an education even more oriented towards the development of these skills, but not sheltered from the world and not built on compliance.

If we want our generation and all future generations to be happy, capable leaders, we need to not just reform our school system but completely change it.