Each of us has experienced firsthand the climate crisis. We try to adapt to it: we wear face masks to brave the smoke-filled air outdoors or set air purifiers to clean it indoors, turning up the air-conditioner to insulate ourselves from the unbearable heat, preparing to evacuate our homes, if need be, when another storm threatens to wreck the coasts.

The climate crisis is everywhere around us: our streets are littered with scraps of plastic, cigarette butts, and other junk. Our local rivers and shores are diluted with industrial sludge. Many of us look up at the night sky only to observe a gloomy pitch-dark, not the tapestry of the cosmos looking over us.

The climate crisis prompts questions that challenge our way of being: “Who am I in this increasingly unstable world? What will become of me and those around me, in the long-run?” Such questions can drag us to an existential pickle, but, as we will see, they can also positively challenge the way we think about the world.

Our political and economic circumstances lead us to think of ourselves as cogs in a machine, of our identity in terms of the hoops we need to jump through over the course of life: go to college to secure well-paying jobs, climb the property ladder, and make sure we have adequate savings for retirement. The climate crisis can help motivate us to rethink these presuppositions. The world is as we see it, and if we are to lead good lives for the benefit of society and nature, we need a richer concept of the self – a fully-realized self that is worth preserving.

Self-realization acknowledges our drive to preserve ourselves and persevere in the face of a cataclysmic climate struggle. It’s not enough to let the world boil over while merely protecting our personal selves. We are part of a vast, interconnected universe, where our wellbeing crucially depends on maintaining relationships and connections with others, including nonhuman others – nature, Earth, as well as flora and fauna that inhabit our planet.

The World Wide Web

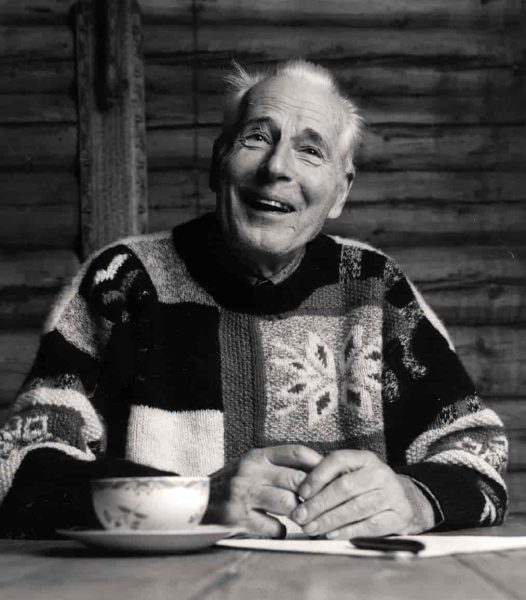

In 1973, the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss (1912-2009) coined the concept of deep ecology. The main idea of deep ecology is that we should address the ecological crisis through a paradigm shift. Rather than tinkering with concrete targets (such as CO2 emissions), we must radically re-envision how we engage with the world. Næss was a wide-ranging philosopher with varied interests. Among many other things, he was a huge fan of the Sephardic Dutch philosopher Baruch de Spinoza (1632-77), particularly of his treatise Ethics (1677), which Næss re-read frequently, and which plays a key role in his ecosophy, or environmental philosophy.

Næss was a man of polarities: on the one hand, he was a member of a distinguished Norwegian family, appointed as a full philosophy professor at Oslo aged 27 – in fact, the only philosophy professor in Norway at the time. On the other hand, Næss published his extensive works with little regard for prestige or fame, including in obscure ecological magazines with small print-runs. This partly explains why Næss remains relatively unknown in English-speaking philosophical circles.

Especially in his later life, Næss approximated what his friend and fellow environmental philosopher George Sessions called a “union of theory and practice,” exercising his ecosophy by spending extensive time outdoors, hiking and mountaineering until well into his 80s. After retiring early, he gave much of his pension away to various projects such as the renovation of a Nepalese school. Næss’s notion of self-realization is inspired by many philosophical traditions, including Mahayana Buddhism and Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolent resistance.

Another important inspiration for Næss came from Spinoza. According to his Ethics, everything in nature has a conatus, a fundamental striving to continue to exist: “Each thing, as far as it can by its own power, strives to persevere in its being.” We see this fundamental tendency not only in humans but also in trees, spiders, and hydrangeas, and even inanimate objects such as houses, mountains, and ponds. Things don’t spontaneously disintegrate and they tend to keep their form over time; even something seemingly volatile like a fire will try to keep itself going. How can we understand this universal drive?

Næss situates the conatus in a bigger picture of nature, namely, one that helps us to persevere and affirm ourselves as expressions of nature. Spinoza argued that there is only one substance, which he called “God” or “Nature.” Nature and God are coextensive, as God encompasses all of reality. So, Spinoza’s God is similar to what we now call the “universe,” the totality of all that is. This totality expresses itself in infinitely many forms, such as thought and physical bodies. We, like everything else, are expressions of this one substance.

Unlike a traditional theistic God, Spinoza’s God has no overall higher purpose. This God is perfectly free and acts in accordance with its own laws, but doesn’t desire anything. Nature simply is as it is, and it is perfect in itself. As Næss put it in 1977, “If it had a purpose, it would have to be part of something still greater, e.g., a grand design.” As Næss interprets him, Spinoza’s metaphysics is fundamentally egalitarian. We are on an ontological par with salamanders, oceans, and berries. A bear’s interests roaming about in the Norwegian countryside matter just as much as those of the surrounding farming communities.

Nature as a whole expresses its power in each individual thing. It is within these expressions of power that we can situate the drive to preserve our own being. To actualize ourselves, we need to understand what our “self” is. Næss thinks that we deceive ourselves, writing in 1987: “We tend to confuse it [the self] with the narrow ego.”

Self-knowledge is partial and incomplete, and this lack of knowledge prevents us from being ourselves. Spinoza believed that knowledge and increased self-understanding help us to elevate our ability to take action, and hence our ability to persevere. We can realize this expansive conception of self by considering our relation to place, an idea that Næss draws from Indigenous thought. We often feel attached to places of natural bounty and beauty, to the point that we might feel that, as Næss said, “If this place is destroyed something in me is killed.”

Loss of place has by now well-documented effects on mental health, including eco-anxiety, which arises from a sense of loss of places to which people feel a strong emotional connection. When our surroundings are hurt, we feel hurt too. For instance, Inuit communities in northern Canada feel homesick for winter. This spontaneous feeling of connection to place signals to us that our self does not end at our skin, but that it includes other creatures and objects. Indigenous people, through their activism and landback movements, demonstrate that there is more to the self than these metrics.

In a letter in 1988, Næss tells the story of an indigenous Sámi man who was detained for protesting the installation of a dam across a river, which would produce hydroelectricity. In court, the Sámi man said this part of the river was “part of himself.” Differently put, if the river was altered, he would feel that the alteration would destroy part of himself. In his view, personal survival entailed the survival of the landscape.

For Næss, there is no grand, external purpose to our lives, other than the purposes that we assign to them. But because our wellbeing depends on factors outside of us, we can still be better or worse off, and it is natural to strive to be better off. In this sense, self-realization is distinct from happiness. A tree that flourishes and does well, with leaves gleaming in the sun and birds nestling on its branches, and it is realizing itself — although we may not recognize that it is happy.

Self-Expression Under Crisis

Drawing together these insights from Næss and Spinoza, we can say that the climate crisis seriously stymies our ability for self-expression. Its degradation of our sense of place and belonging in the modern era makes it difficult for us to realize ourselves as human beings. Increasingly, we are pushed to settle for safety from immediate threats posed by the degradation and toxification of the environment. We cannot even begin to think about how to preserve ourselves in all the diverse aspects of our existence, and therefore, we cannot really thrive. This is in part why the climate crisis is so corrosive to our sense of self: it stifles our ability to know ourselves.

Self-realization implies a unity of acting and knowing; you need to know yourself accurately as part of a world wide web, and as more than a narrow ego. Once you know this, you can begin to act. By contrast, a lack of self-knowledge (of ourselves, as conceived of a larger whole) immobilizes and disempowers. Unfortunately, the climate crisis is undergirded by massive denialism. This denialism is more than us looking away as individuals. It is bankrolled by wealthy elites and fossil fuel companies in the face of inescapable climate degradation.

The super-wealthy have tightened their grip on democracy, creating politically motivated diversion tactics, such as blaming so-called “metropolitan elites” (educated people) for the worsening economic circumstances of working-class people, or pointing the finger at refugees arriving in precarious boats on the shores of wealthy countries. The climate crisis lies behind nostalgic nationalist throwbacks to some imagined past, such as MAGA and Brexit.

These movements represent a novel political order that is based on climate-change denial, where wealthy elites aim to create gated communities and escape routes by deregulation and disenfranchisement. All the while, they try, in vain, to realize themselves in things that seem ultimately unfulfilling and empty: superyachts, short trips into space or into the deep sea, and buying up or surfacing entire islands from the seas.

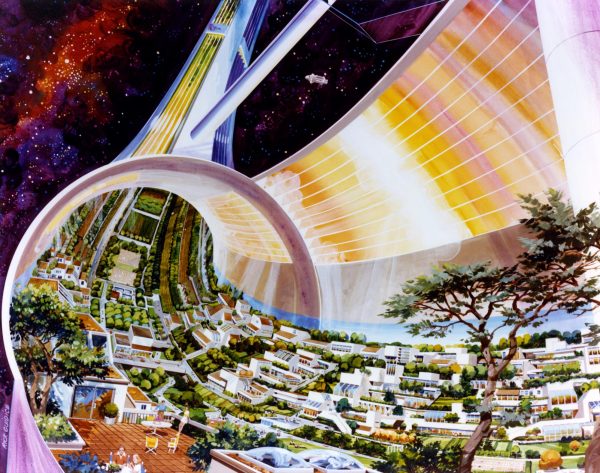

By influencing and subverting the democratic process, wealthy elites try to encourage deregulation so as to pull more and more resources toward themselves. Realizing that this is not sustainable, they retreat into increasingly remote fantasies such as TESCREAL, an ideological bundle of -isms: transhumanism, extropianism, singularitarianism, cosmism, rationalism, effective altruism and longtermism. It is promoted by philosophers at the University of Oxford such as Nick Bostrom, Hilary Greaves, and William MacAskill, and found enormous support from tech elites at Silicon Valley such as Elon Musk, Sam Altman, and Peter Thiel.

The TESCREAL ideology anticipates a time when advanced technologies enable humanity to accomplish things like: producing radical abundance, reengineering ourselves, becoming immortal, and colonizing the universe and creating a sprawling “post-human” civilization among the stars, full of trillions and trillions of digital people. The most straightforward way to realize this utopia is by building superintelligent AGI (artificial general intelligence).

The happiness of these future posthumans, according to the TESCREALists, justifies neglecting current-day problems. “For the purposes of evaluating actions,” Greaves and MacAskill wrote, “we can in the first instance often simply ignore all the effects contained in the first 100 (or even 1,000) years, focusing primarily on the further-future effects. Short-run effects act as little more than tie-breakers.” However, the TESCREAL world leaves little scope for the diversity of expression of being human: the joyful, vulnerable ways of being in, for instance, indigenous societies, rural communities, nomadic tribes, and more.

Why do the wealthiest people seek to actively deny the climate crisis rather than address it? Perhaps it is because we are in the grip of bad emotions. Normally, our emotions help us seek out what is good for us and avoid what is bad. We have three basic affects: joy, sadness and desire. Desire is an expression of the conatus [a natural impulse or striving]: we seek things that bring us joy and avoid things that bring us sadness. Overall, this aids our self-preservation. However, because of the complex ways in which our emotions intermingle with the outside world, it is possible to be mistaken in them and to desire things that do not help us to realize ourselves. Seeking prestige, fame, and wealth seems like it will help us to realize ourselves, but in actuality, we are gripped by their power.

While these misconceptions are prominent among the wealthiest elites, we see them in everyone. It might be that we are all climate crisis deniers in some sense. Not that we literally deny that there is a climate crisis or influence policy to fuel denialism, but that we look away, much like a person in grief who realizes someone is dead but has not been able to integrate the loss into her life. We might say it is real, but we rarely feel or act like it is. We might go to an airline booking site to visit a friend for the weekend; we might think that we will see the Great Barrier Reef some day.

And the reason for this is, in part, that we feel like addressing the climate crisis would demand substantial sacrifices on our part, which seems like a drop in the ocean given the scale of the problem. As Næss writes, “when people feel they unselfishly give up, even sacrifice, their interest in order to show love for Nature, this is probably in the long run a treacherous basis for conservation.” How, then, do we get out of this situation of collective denialism?

Achieving The Blessed World

We have now seen what self-realization is and how it is tied to knowledge. By increasing our knowledge, we increase our power. For example, knowing that pathogens cause infectious diseases led to great advances in preventing or reducing transmission through vaccines. Similarly, to be able to act in the face of the climate crisis, we need knowledge, and for that we can look directly at Spinoza’s life for inspiration.

Spinoza lived a very sparse, propertyless existence in rented rooms, and tried to stay away from fame and the limelight. He declined a prestigious professorship at the University of Heidelberg, and did not wish to be named as the sole heir of a friend, even though it would have made him independently wealthy for life, choosing instead to grind lenses to sustain himself. Spinoza did not think that flourishing or, in his terminology, “blessedness” (beatitudo) could be found in material wealth and fame. Instead, his modest work as a lens-grinder offered him more avenues for self-realization, because it made him part of the interdependent, budding community of early scientists at the start of the scientific revolution, many of whom used lenses in their telescopes to gaze at the stars or in their microscopes to observe bacteria.

While Spinoza did not see blessedness in this worldly wealth, he didn’t think it could be found in an afterlife, either. In the 17th century, people commonly believed that you could achieve blessedness after you died if you followed the moral norms and willingly abstained from certain pleasures during your lifetime. However, Spinoza’s radical insight is that you can achieve blessedness in this life. As he wrote: “Blessedness is not the reward of virtue, but virtue itself; nor do we enjoy it because we restrain our lusts; on the contrary, because we enjoy it, we are able to restrain them.”

The notion of blessedness cuts to the heart of Spinoza’s view of self-realization. It requires that we accurately understand ourselves as modes of God and thereby come to love God. But what does such an accurate understanding entail? For Spinoza, blessedness is a kind of repose of the soul or mental acquiescence. It arises from the love of God or nature. For Spinoza, knowledge increases our power, and hence our self-preservation, by knowledge. If our emotions mislead us, we inhibit our self-preservation because we are pushed to serve external goods. The highest knowledge we can hope to achieve is knowledge of the universe as a whole. This knowledge is also knowledge of the self, because each of us is an expression of God. Each of us – an individual sparrow, a wildflower, a mountain or a cloud – “expresses the whole, in its own particular way,” as Spinoza wrote.

Once you realize that you are an expression of the whole of nature, you come to realize that, although you will someday pass, you are also eternal in an essential sense, since the substance of which you are an expression will endure. Spinoza also makes the strong claim that, if we are rational, we cannot but love God. It is the rational thing to do, because the love of God spontaneously and naturally arises out of an accurate understanding of ourselves and the world. Once we realize this, we achieve blessedness.

Once we achieve this, we no longer have to constrain our lusts, because they will dissipate when we achieve this cognitive unity with the rest of nature. All this talk about tempering one’s lusts may feel moralistic and old-fashioned, but Spinoza brings up an important point. Engaging in pursuits such as last chance tourism – visiting places on Earth soon to disappear due to the climate crisis – or deep-sea exploration for fun is ultimately self-destructive (in the sense that it accelerates environmental degradation, and therefore acceleration our own degradation). Similarly, we might feel that renouncing steak, or giving up flying for the pleasure of travel, might be restraining ourselves.

But once we understand ourselves as ecological selves, and understand how we are part of fragile, large ecosystems and the planet, this will feel like preserving our expanded self, rather than cutting ourselves short. As Spinoza explains in his unpublished work Short Treatise on God, Man and his Well-being (1660), “since we find that pursuing sensual pleasures, lusts, and worldly things leads not to our salvation but to our destruction, we therefore prefer to be governed by our intellect.”

Paradoxically, we underestimate how rich our ecological selves really are. We don’t give ourselves enough credit on how we are able to derive genuine contentment and wellbeing from simple pleasures that do not involve destroying the planet. Rather, we think that we need infrastructure-heavy, expensive things to make us happy, where happiness always lies just around the corner.

Self-realization increases our power. Active enjoyment of life in a Spinozist sense is a psychological understanding of yourself and your relationship to the world. There is a beauty about self-realization. Through introspection and rational conduct, we would be able to find new citizenship, a new way of being in nature, a new existence that includes the animal kingdom and plants. This way of being increases our power of acting, and responds to our propensity for self-realization.

There is not one set way for us to be. There is not even an ideal that humans must evolve toward, as in the TESCREAL universe. Nature has no ultimate teleology, and no final destination. We matter as we are right now, not only or mainly as future hypotheticals, and we can envision a world where humans, animals, plants, mountains, and rivers have their own multifaceted identities and where they exist in community with each other. Such a world holds diversity of thought and expression. Our way out of the climate crisis begins with a reconceptualization of ourselves as ecological and interconnected selves.

Self-realization as conceived by Næss and Spinoza is at heart a joyful, affirmative vision. It does not start from the premise that life is inherently filled with suffering. Once we achieve self-realization, living well becomes easy due to the unity of blessedness and virtue. However, it is difficult to attain because of our collective climate denialism. It’s not that one day we’ll wake up and be self-realized. We need to pursue that change of perspective and realize we can flourish only with the rest of nature. Soon enough, the world will depend on it.

Nature has no ultimate teleology, and no final destination. We matter as we are right now, not only or mainly as future hypotheticals, and we can envision a world where humans, animals, plants, mountains, and rivers have their own multifaceted identities and where they exist in community with each other. Such a world holds diversity of thought and expression. Our way out of the climate crisis begins with a reconceptualization of ourselves as ecological and interconnected selves.