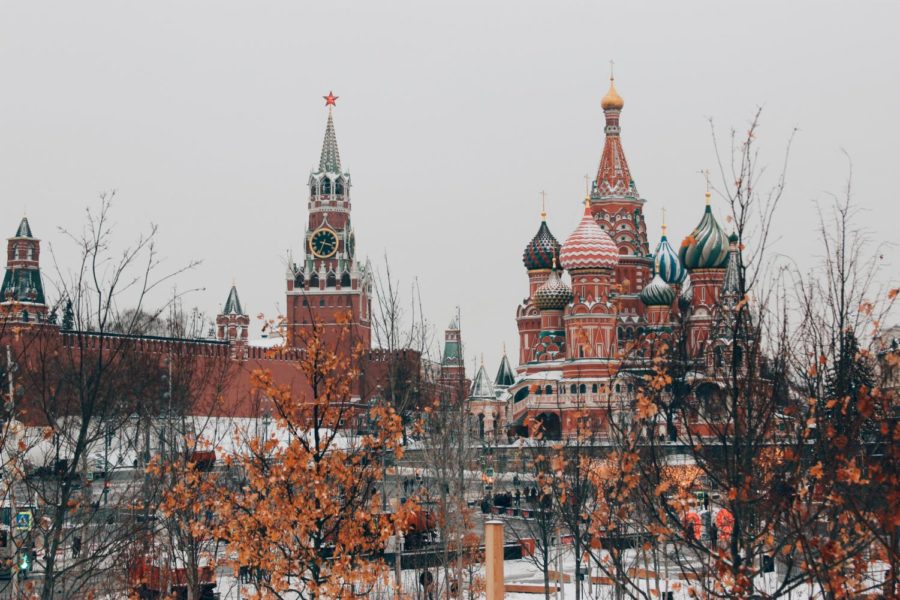

The Roots of Russian Nationalism

An analysis of some of the underlying causes for a rise in Russian nationalism.

What are the roots of Russian nationalism?

Vladimir Putin enjoys an 83% approval rating as of late March 2022. For reference, Harry Truman’s approval rating at the conclusion of the Second World War was 87%, only 4% higher. The President of Russia has not freed Europe nor has he overseen one of the greatest economic booms in his nation’s history, yet Russians rally around him.

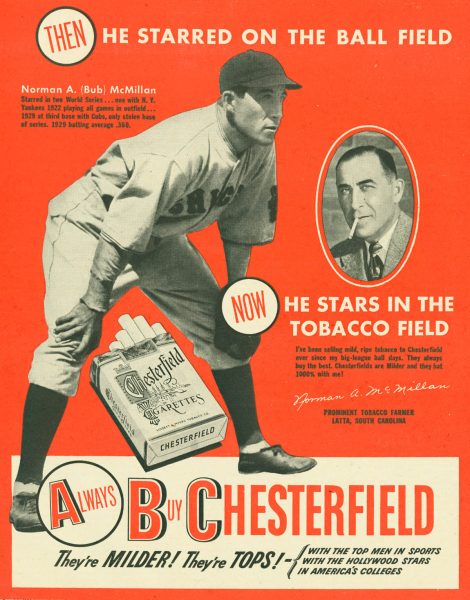

The propaganda leading up to the invasion of Ukraine has been rife with this kind of rhetoric. The war has been pitched exclusively as a “special operation” to rid Russia of foreign influence and to protect the nation’s territorial integrity against the NATO bogeyman.

Although the Russian regime has approached the West with hesitance since Putin’s election in 2000, its rhetoric turned particularly anti-Western in the late 2000’s after the full consolidation of his power. This also marked an economic shift away from European integration and towards first regional cooperation in the Former Soviet Union and to a large extent an autarky (a country, state, or society which is economically independent). Independent nationalist groups rebounded around the same time as the oil-related economic boom that Putin had staked a lot of his legitimacy on, faltered.

In addition to distributing some of Putin’s popularity around Russia’s political movements, worse conditions necessitated a scapegoat. Russia is a Federation of many smaller republics such as Chechnya, South Ossetia, Crimea, and many others. As the oil boom waned, many Russians blamed their hardship on those from the South Caucasus and Central Asia. Groups like the Movement Against Illegal Immigration (DPNI) found many people willing to march under the slogan of “Stop Feeding the Caucuses.”

The number of hate crimes recorded by the Moscow SOVA center, the nation’s premier tracker, reached record highs. In its simplest form, this nationalism is a lot like the traditional understanding of the ideology, a collection of neo-fascists largely consisting of radicalized youth.

However, nationalism does not inevitably lead to pogroms. In fact, its roots are in 19th century liberalism. At the time, nationalism was seen by intellectuals around Europe as a way to entice positive reform. After all, acknowledging the importance of the nation above all also meant acknowledging the importance of the people that constitute it as more than just subjects of a divine monarch.

Before Bismark used these ideas for his own reactionary ends, the Prussian king was offered the opportunity to become ruler of a Germany that had a liberal constitution and institutions. The Russian people were unable to endure the pain of economic liberalization in the 1990’s following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. They were left with a scar that even now makes many hesitant if not outright hostile to free market ideas. On the other hand, many of the other former republics such as Poland weathered the storm of the first terrible decade largely because of the unifying force of nationalism.

Although the Russian regime has approached the West with hesitance since Putin’s election in 2000, its rhetoric turned particularly anti-Western in the late 2000’s after the full consolidation of his power.

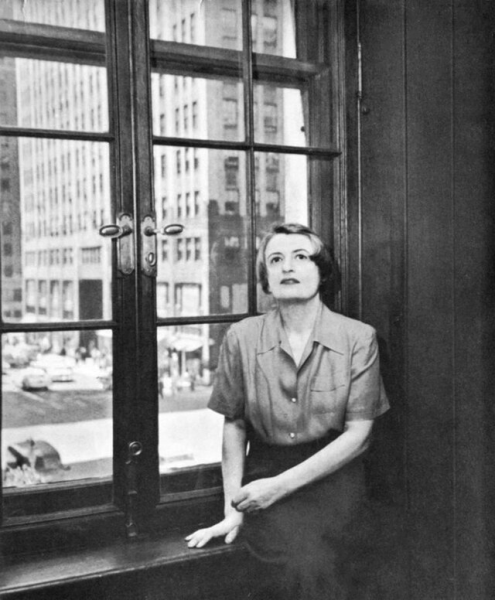

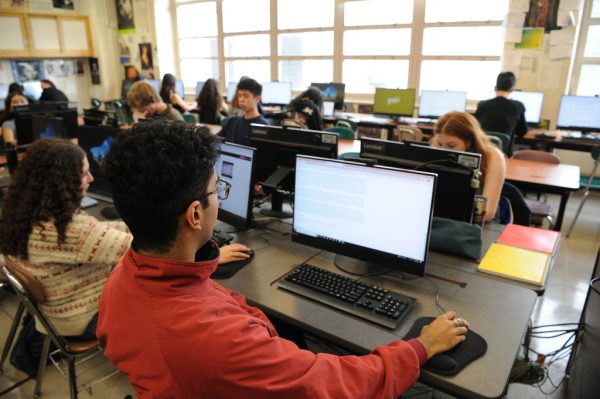

Anton Karp is a News Editor for 'The Science Survey.' He is most interested in the research that goes into the journalistic writing process. Anton values...