Classic Literature is Monochrome: The Need for Reshaping the Western Canon

Readers are drawn to stories in which they see themselves. But what happens when the Western Canon is comprised of books that are largely confined to one racial group?

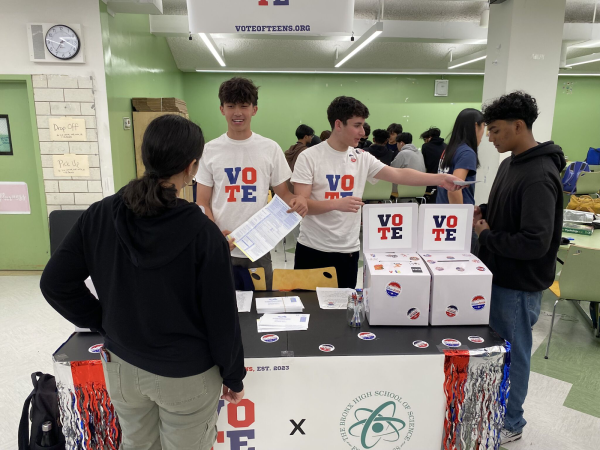

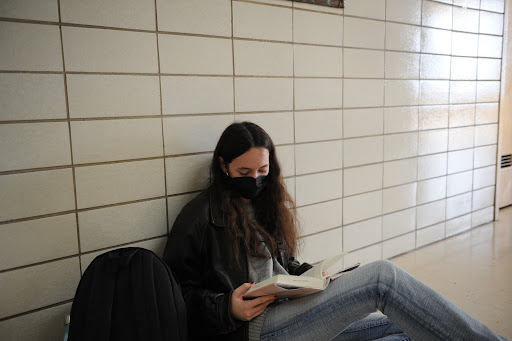

Reading works from diverse authors resonates with Bronx Science students and teachers. Here, Genevieve Morange ‘22 is reading ‘The Idiot,’ a semi-autobiographical novel by Turkish-American author Elif Batuman. Selin, the main character, is a linguistics student at Harvard who struggles to fathom adulthood, the world, and her own identity.

My eyes dart between the variety of leather bound classics on the bookshelves at Barnes & Noble, each title inviting my curiosity. The Great Gatsby. Little Women. 1984. Frankenstein.

While these classics are all critically acclaimed as some of the “greatest novels of all time,” they all share another underlying resemblance — a lack of diversity.

Classic literature is known for its timelessness and influence, and it reflects society’s development over the past several centuries. As far back as Ancient Greece, however, classics have often only told one side of the story — that of Caucasian authors and their characters. A quick Google search of “classic authors” reveals a row of caucasian writers, dozens of men with neat mustaches and pipes.

Writers such as Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, and the Brontë sisters are among the few women that we now applaud as being canonical writers, but they were heavily criticized in their time. While they exhibit the small steps made towards more inclusivity, classic literature needs to provide wider representation, both in race and gender, in order to appeal to modern society and today’s readers.

“Books are often far more than just books,” said New York Times bestselling author Roxane Gay in her essay collection Bad Feminist.

Rudine Sims Bishop, professor at Ohio State University and the “mother” of multicultural children’s literature, uses metaphors of windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors to emphasize this. While books serve as windows and sliding doors to let readers into different worlds, they also act as mirrors, casting a reflection of the reader within the pages.

“When children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read, or when the images they see are distorted, negative, or laughable, they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in the society of which they are a part,” she said.

Unfortunately, in 2018, only 1% of children’s novels featured a BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) protagonist.

This number is a problematic one, but it is nothing new.

“We read, so that we don’t feel alone,” said Esther Gelman ’24. “I think that’s especially why representation is so important, because you need to have people that are like you in order to relate and genuinely feel understood by characters.”

In fact, this single statistic subtly plays into the larger issue of declining literary reading. The percentage of Americans who read some form of literature fell to 43% in 2015, the lowest it has been in the last three decades. In 2017, a mere 19% read for leisure.

Although the readership for classic novels is fading, their use in high school, college, and university classrooms around the world is as prominent as ever. Referred to as the Western Canon, this selection of classic texts, artworks, and philosophies is largely embraced by today’s education system.

While the Western Canon undeniably holds importance, it fails to reach its target audience. “The problem is that when you say dead white men write such books, it automatically suggests people of other nationalities and races can’t really do the same thing, and we tend to just adopt this as the default,” explained Mr. Young Kim, English teacher at Bronx Science.

This default and social norm is the main contributor to the lack of diversity in nationwide school curriculums. A study from the NYC Coalition for Educational Justice found that in New York City elementary schools, 84% of the authors in commonly-taught books are white.

Although this trend is primarily observed in elementary schools, it continues to influence students’ mindsets long after they graduate. “Most students can name dozens of authors who they’ve been required to read from middle school to high school who are white men, but naming Black, Hispanic, or Indigenous authors to that same degree would be almost impossible,” added Chanel Richardson ’22, Senior Editor of Dynamo, Bronx Science’s literary magazine.

In recent years, there have been great efforts to make literature more inclusive and diverse, both at Bronx Science and within the publishing industry.

Penguin Random House, for one, has launched a new project: Penguin Vitae. According to Elda Rotor, Vice President and Publisher at Penguin Classics, the five-part hardcover series intends to adopt a post-Eurocentric literary worldview and strengthen marginalized voices across the board. In 2020, Penguin Classics was the first to publish Romance in Marseille by Claude McKay, a Jamaican-American writer, 87 years after it was written.

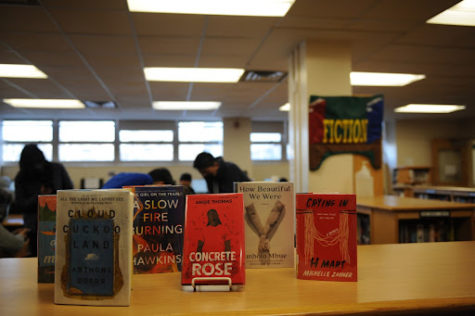

Likewise, Bronx Science has integrated POC and female authors to its Summer Reading List, with works like Pachinko by Min Jin Lee ’86. Aside from reading the required book for their grade level, students are also encouraged to choose a literary work from the Diversity List, featuring The Color of Law, Crying in H Mart, A Thousand Splendid Suns, and many more.

“Including more voices is something you need to actively be doing all the time,” said Ms. Nicole Scotto, who teaches Global History and AP European History.

The concept that books can be a catalyst for systemic issues is a hard pill to swallow, but it’s an important first step towards educating today’s generation about representation in literature and history. In essence, publishing a few special editions of books with POC authors and characters is only another form of performative activism, and it is not enough.

As Pamela Mason, Senior Lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education puts it, “Moving away from the classics toward more diverse books can stretch people’s imaginations and pedagogy.” Until there is substantial change being implemented into curriculums nationwide and a real shift in mindset, the racial and gender prejudices in classic literature will continue to influence readers’ own biases.

While we cannot reverse the social norms that have already been ingrained in classic literature, one certainty renders itself clearer than ever: the need to reshape the Western Canon.

While the Western Canon undeniably holds importance, it fails to reach its target audience. “The problem is that when you say dead white men write such books, it automatically suggests people of other nationalities and races can’t really do the same thing, and we tend to just adopt this as the default,” explained Mr. Young Kim, English teacher at Bronx Science.

Charlotte Zhou is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ In addition to writing and editing articles, she constructs the online crossword and...