It’s Time To Ban Dark Money Contributions

How dark money allows the 1% to have a disproportionate influence on the electoral process.

During the 2020 presidential election, over $30.5 million was spent by non-disclosing 501(c)(4) and 501(c)(6) organizations as independent expenditures.

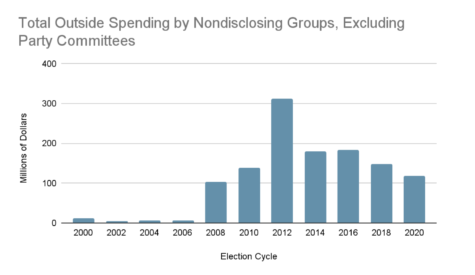

The 2012 presidential election saw an unprecedented increase in a new type of financial support for the two major candidates: dark money. How much of this money was there? $143.9 million.

Dark money refers to political spending in the form of independent overtures that cannot be traced back to their original source. That election, which was the first major one operating under the new deregulated guidelines established by the Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United v. FEC, marked the beginning of dark money’s meteoric rise in the American electoral process.

The anonymity of dark money prevents citizens from being aware of who and what are influencing their representatives, allowing for corporations and exceedingly wealthy individuals to wield disproportionate power over the democratic process. Therefore, it is time to ban dark money and require disclosure in all forms of campaign financing, both direct and indirect.

However, before arguing for such reforms, it is necessary to establish the three basic ways a campaign can be financed, excluding individual donations and public funding: (1) political action committees (PACs), (2) super PACs, and (3) dark money groups. Each of these organizations have varying levels of regulation with regards to how they receive and spend their finances.

PACs, the most regulated of the three, must be registered with the Federal Election Commission (FEC). They are required to disclose the source of their donations and are limited in both how much an individual can contribute to the group ($5,000 per year), and how much the organization itself can contribute to each candidate ($5,000 per candidate per election cycle). Despite these restrictions, PACs are still permitted to donate directly to a candidate’s campaign, unlike super PACs and dark money groups.

Super PACs were conceived following the 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. FEC, which deregulated many aspects of campaign financing. They are also required to disclose the sources of their contributions, but there are no limits on those contributions and no limits on how much super PACs can spend on independent-expenditures. This leads us to the third, and perhaps most insidious, form of campaign financing: dark money groups.

Dark money, which sounds as mysterious and sinister as the dark web, simply refers to political spending, independent of a campaign, by organizations not required to disclose their sources. Dark money organizations, usually designated as 501(c)(4) “social welfare groups” or 501(c)(6) trade organizations, may receive unlimited contributions from anonymous donors, meaning that a wealthy individual (or corporation) can financially support a candidate or political platform indirectly while concealing their identity.

In 2020, $118.97 million was spent by groups that do not disclose donors, excluding party committees. Dark money can also worm its way into the political system as donations made by shell companies to source-disclosing super PACs.

Political reform group Issue One, reported that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a powerful lobbying organization (and 501(c)(6) non-profit), received a total of $1.3 billion in donations from 2010 to 2016. One of these donors was identified as the Dow Chemical Company, which contributed $13 million. Issue One also found that one of the top donors to the 60 Plus Association, a conservative advocacy group that supports the privatization of Social Security, was American Encore (formerly known as the Center to Protect Patient Rights). This organization has been found to have close ties to the Koch brothers. Since 2009, American Encore has donated $16 million.

Non-disclosure rules allow individuals like the Koch brothers and corporations like Dow to have a shadowy influence over elections by providing the funds needed to remain competitive in a political landscape that requires massive outreach through countless TV ads and media campaigns.

Once these special interest groups establish this seemingly transactional relationship, they ostensibly secure a channel through which they can exert influence. The catch here is that they can do it discreetly, all the while claiming that democracy is at work.

AP U.S. Government and Politics teacher Ms. Elizabeth Meyer, agrees. “I can’t imagine a world where dark money groups do not undermine our democracy,” she said. “Oftentimes, the candidates who are supported are in favor of policies that promote the interests of big businesses and the wealthy rather than everyday American people.”

How can politicians who quietly accept donations from Big Money adequately represent the American people, of whom two-thirds support increasing taxes on the very rich? Who are politicians truly representing: the corporations who fund them or the people who elect them?

Angelena Bougiamas ’22, a student in Ms. Meyer’s class, adds, “Non-disclosure threatens voters’ abilities to be as informed as possible on the candidates they’re voting for.” Our current system caters to the needs of the donor class by giving them the power to siphon off funds to candidates they deem would serve their corporate interests, and as a result denies voters the opportunity to be as adequately represented. They have a right to know who or what is exactly influencing the politicians they support. Banning non-disclosure would help to mitigate this problem by creating more transparency in a process that is primed for corruption.

Dark money reforms are also necessary to keep foreign nationals from embedding themselves in this country’s politics. To clarify, these individuals are already prohibited by the FEC from making contributions to campaigns or even independent expenditures regarding any federal, state, or local election. They are also not allowed to donate to any organization associated with a political party.

A recent ruling has given overseas contributions more leeway. In response to Montana Trout Unlimited’s allegation that a Canadian subsidiary of Sandfire Resources (an Australian mining company) illegally contributed money to prevent a restriction of hard rock mining in Montana, the FEC held that donations for ballot initiatives were permitted, whereas donations for elections were not. Ms. Meyer rightfully articulates that this decision “allows transnational corporations and international business leaders to fund specific ballot initiatives that promote deregulation and that protect their business interests and profit motive.”

Despite these restrictions, foreign nationals could still influence elections by making individual contributions to dark money groups, allowing them to remain anonymous, or they can use a middle man and donate to super PACs. Essentially, foreign corporations can establish U.S. subsidiaries with 501(c) non-profit status and contribute financially to super PACs. These super PACs are still required to disclose donations by FEC guidelines, but they will only be able to share an indirect source and avoid the direct disclosure of the corporation.

Even still, foreign corporations can establish shell companies by exploiting a loophole that does not require limited liability companies (LLCs) to disclose beneficial owners, and these LLCs can donate directly to Super PACs, 501(c) groups, or invest in real estate. Either way, the influence of foreign individuals, corporations, or even governments is possible. These side-channel options are precisely why non-disclosure rules need to be overturned.

The countless opportunities for elites to influence policy from the shadows induces feelings of hopelessness in the average voter, but there are alternatives to dark money which directly engage with the people. One of these options is public funding. Under this system, individuals can indicate if they want to contribute a certain amount of their income tax to a particular presidential election campaign.

Campaign finance reform organizations, such as Take Back Our Republic and Represent Us, have already been suggesting different ways to encourage taxpayers to participate, such as offering tax incentives. Take Back Our Republic has been a proponent of instilling a $100 tax credit for those small donors. With incentives like these, it may be possible to increase the number of individuals interested in contributing to public funding, thereby strengthening its feasibility.

Both Meyer and Bougiamas agreed that this method would decrease the role of the 1% in politics. “The financing is anonymous and everybody contributes the same amount, so politicians are more incentivized to legislate fairly once they’re in office,” Bougiamas said. Ms. Meyer offered a concurring opinion, stating, “It would level the playing field by preventing big money in politics and by ending the endemic corruption in government today.”

Who are politicians truly representing, the corporations who fund them or the people who elect them?

Meriel Crowley-Wang is an Editorial Editor for ‘The Science Survey.' She enjoys the logical way in which journalistic writing presents itself to the...