Sufficiently Dignified and Sufficiently Independent: A Case For the Repeal of the 17th Amendment

How the Progressive Era reform led to the state in which we find the Senate today.

Alexander Hamilton, who now adorns our 10 dollar bills, felt that the Senate’s independence from electoral troubles was what allowed it to be a sufficient court of impeachments.

The United States Senate acquitted Donald Trump for the second time on February 13, 2021. Despite 50 Democrats and only 7 Republicans voting to convict, it was the most bipartisan conviction vote for any impeachment in American history.

Those seven Republicans were Richard Burr (R-NC), Bill Cassidy (R-LA), Susan Collins (R-ME), Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), Mitt Romney (R-UT), Ben Sasse (R-NE), and Pat Toomey (R-PA). Cassidy, Collins, and Sasse are not up for reelection until 2026, Romney is not up for reelection until 2024, and Burr and Toomey had already announced that they would be retiring. Murkowski is the only Republican up for reelection in 2022 who voted to convict.

But why is this even being discussed? Why were Republicans only willing to vote to convict Trump if they knew that their electoral futures were relatively secure? Senators Burr and Cassidy may have been wrong about that stability, as they were both censured by their respective state’s branch of the GOP for voting to convict. The Pennsylvania GOP had also attempted to censure Senator Pat Toomey, but was unable to come to an agreement on a resolution doing so.

If impeachments are supposed to be judicial processes where each Senator must take an oath to “do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws,” then why has it devolved into such a political affair?

This is certainly not how the framers of the Constitution envisioned the impeachment process to work. The framers did not invent impeachment themselves; they borrowed the process from the United Kingdom. Impeachment, however, is not the method by which leaders such as the Prime Minister are removed from power in the United Kingdom. Instead, they can call for a vote of no confidence. This is a purely political process where the House of Commons votes on whether it has confidence in the current government. If they do not, a new government must be formed or new elections must be called. Impeachment in the United Kingdom, on the other hand, is a process that allows parliament to prosecute government officials for crimes they had committed in office. Somebody impeached by the House of Commons could theoretically be punished by more than simple removal from office. However, impeachment has not been used in the UK since 1806 since it places a heavy burden on the Parliament that is not present in a simple vote of no confidence.

The framers, therefore, deliberately adopted the impeachment process instead of the no-confidence process as a Constitutional mechanism for Congress to remove officials. Whereas British trials of impeachment are presided by the House of Lords, a body of aristocrats with no direct obligation to the people, the framers substituted it for the Senate. “Where else than in the Senate could have been found a tribunal sufficiently dignified, or sufficiently independent?” wrote Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 65. “What other body would be likely to feel confidence enough in its own situation, to preserve, unawed and uninfluenced, the necessary impartiality between an Individual accused, and the representatives of the people, his accusers?”

When Hamilton talks of the “representatives of the people,” he is referring to the House of Representatives, which is given the sole power to levee articles of impeachment against public officials. Hamilton does not give the Senate the title of “representatives.” Rather, they are dignified and independent, able to serve as an impartial jury and to examine the accusations made by the people. This hardly sounds like the Senate that acquitted President Trump, and that is because it is not the same Senate.

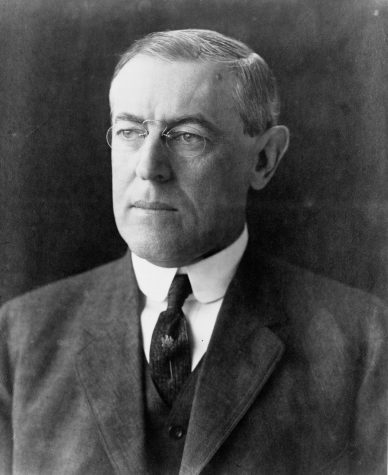

In the original Constitution, Senators were chosen by the legislature of the state that they were from. In 1913, the 17th Amendment went into effect. This amendment took the power to elect Senators away from State legislatures and gave it to the people of each state. The amendment came during the ‘Progressive Era,’ which also saw the revisions of the Constitution to allow for income tax (16th Amendment), ban alcohol (18th Amendment), and give women the right to vote (19th Amendment). All of these amendments were ratified between 1913 and 1920, during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency.

Wilson was a champion of progressive ideas and saw them in opposition to the principles of the founders: “If you want to understand the real Declaration of Independence,” Wilson said in 1911, “do not repeat the preface.” The preface is, of course, the part of that document we all remember. It is there where Jefferson discusses the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal,” and it is also there that our “unalienable Rights” are discussed. But what Wilson is more concerned with is the main body of the Declaration: the list of grievances by the colonists against King George. To Wilson, addressing the current grievances and problems of the citizens was more important than the philosophy of rights and liberties that went along with it. Throughout his presidency and the progressive era, constitutional protections such as separation of powers and checks and balances were overturned to accommodate the new grievances of the people of the time, such as with the 17th amendment.

“There was a perception of the time that the Senate was very much out of touch and anti-democratic and that it was not standing up well to the rising democratic forces of the late 19th Century and early 20th Century,” Professor Todd Zywicki told Yale’s William F. Buckley Jr. Program in a recent interview. Zywicki is a law professor at George Mason University who has written and spoken extensively on the subject of the 17th Amendment.

Zywicki also spoke to me about the reasons for the amendment’s passage: “Individual state politicians didn’t really want the responsibility to elect Senators because it tied their personal political fate too closely to that of the Senator,” he said. “Many voters voted for their state representatives as a proxy for their preferred Senator (sort of like an electoral college).”

The result is a Senate that is in the exact same position as the House of Representatives; the only difference between the two in terms of how their power is derived is the larger size of a Senator’s constituency. You end up with a system of legislature that is completely antithetical to what the founders envisioned.

“In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates.” James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 51, “The remedy for this inconveniency is to divide the legislature into different branches; and to render them, by different modes of election and different principles of action, as little connected with each other as the nature of their common functions and their common dependence on the society will admit.”

The transformation of the Senate from an independent body and a check on the majoritarian House to a majoritarian body itself has had many consequences over the years. We have seen the 17th Amendment affect things like the confirmation process of federal judges and cabinet officers, but impeachments are the most obvious example — the process that was originally set up was so clearly designed for a group of people that could be impartial and not have to worry about popular reelection.

“It’s at least plausible to think of the Senate as a sort of neutral jury when Senators are indirectly elected,” said Professor Zywicki. “But now, it’s a largely partisan process.” Zywicki also wrote in an article for the Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy that “The procedure established by the Constitution for impeachment may be the most obvious way in which it seems likely that the Framers would have designed the Constitution differently if they had anticipated that Senators eventually would be elected by partisan direct election, as it is today.”

If the Senate remains such a political body, we will continue to see actions such as the irresponsible acquittal of President Trump. The duties of the Senate, which are supposed to be independent and impartial, will be muddled by electoral concerns and ideological alignments. If Republican Senators did not have to worry about whether or not they would be reelected by a voting base that Madison would have called “united and actuated by some common impulse of passion,” perhaps more would have voted to convict. Restoring the State governments’ power to choose their Senators will restore the Senate to the body it was intended to be so it can do the job it was intended to do.

The result is a Senate that is in the exact same position as the House of Representatives; the only difference between the two in terms of how their power is derived is the larger size of a Senator’s constituency. You end up with a system of legislature that is completely antithetical to what the founders envisioned.

Benjamin Fishbein is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey.' He believes that a diverse range of ideas within journalism is important as it fosters thoughtful...