Reflections on the Dioramas of William R. Leigh at the American Museum of Natural History

Some thoughts on the dioramas of William R. Leigh, who overlooked the creation of the dioramas in the Hall of African Mammals.

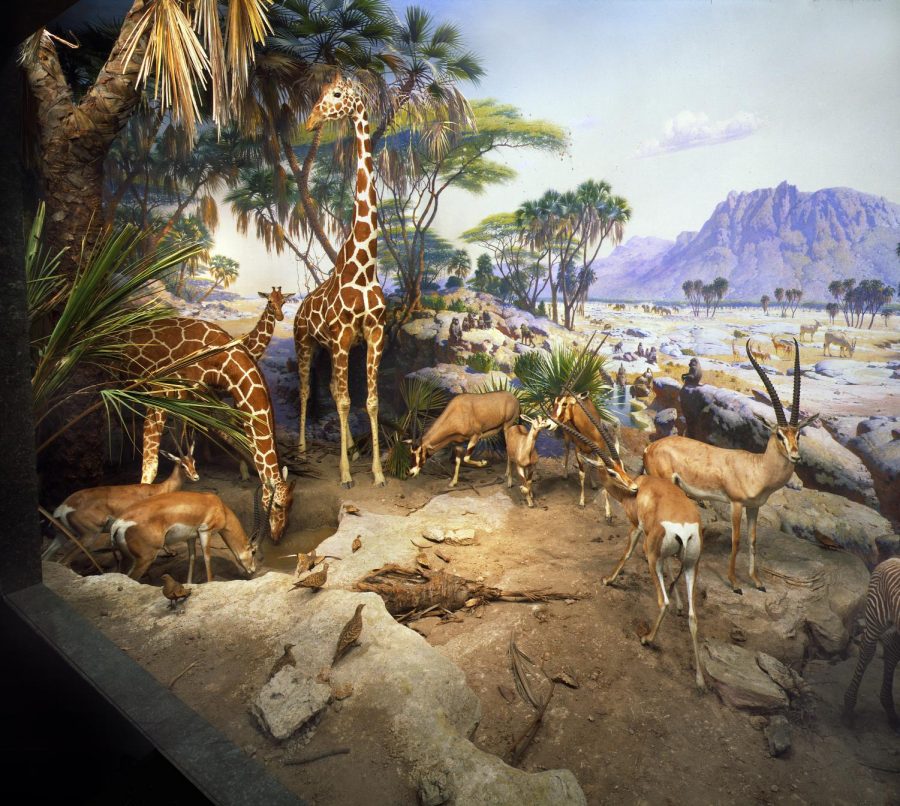

In 1908, Henry Osborn as board president decided on a directive for the American Museum of Natural History: to wed art and science. Their marriage lies within the Hall of African Mammals, a hall of history introduced to us by a chimeric diorama of eight African elephants courtesy of another president — Theodore Roosevelt. And the dioramas go on from there; surrounding us are the numerous displays of gorillas, lions, giraffes, gazelles, zebras, and ostriches. Osborn’s vision is best described by Penelope Bodry-Sanders: “One constant theme that surfaced during his tenure at the AMNH was the potential for marrying artistic values to science to create beautiful, compelling exhibits. These exhibits could communicate the order and splendor of the natural world while at the same time disseminating information about it.”

Each diorama here is more than a means of information: it is an expression of something more. I know it. I know. I can hear. I can hear the voices of history coated in the dark paint covering the horns of the grazing wildebeests.

I will focus on the dioramas of William R. Leigh. He was hired by James L. Clark to overlook the creation of the dioramas in the Hall of African Mammals. I can speak to Leigh’s art, I suppose. Leigh has a distinct surreality in some aspects to his art. Take his waterhole diorama; it employs a purplish horizon over the foreground. Personally though, I prefer a more subdued, grounded approach. Dioramas are three-dimensional. Yes, there is a center in here. However there is more than simply a center. There is a shell at the center. A cocoon of air and paint and whatever else there that all crystallizes and then spreads its wings to the sides. A diorama encompasses all of perspective, dimension, and color, and yet appears to only be an illusion of two-dimensionality to the viewer. We have to use tricks to keep up that illusion and most of all, make that illusion malleable to the viewer’s position relative to the painting.

We all had our tricks. Leigh had his. I used some of his. For example, there is again the waterhole one. Leigh used a line of zebras diminishing in the distance to the right as a perspective device. Its purpose was to reduce the effect of the physical curve of the diorama on the viewer. I used a similar device — but with trees — in another one of my pieces.

But Leigh’s greatest talent was his observation. His reference studies are superb. He would sit and bring back a careful panoramic piece, including the whole background, and he would also bring back a lot of other studies — incidental studies — also very carefully finished, which proved of great use in addition to the primary panoramas. No one could have asked for better background studies to work from than Leigh’s. They were marvelously done. I try to do that too, to observe. It is as if I am a scientist.

Dioramas cannot exist in isolation. They come from life. And it was the muralist’s job to hunt life. He hunted lions, birds, and other creatures for the purpose of art and science.

Dioramas cannot exist in isolation. They come from life. And it was the muralist’s job to hunt life. He hunted lions, birds, and other creatures for the purpose of art and science.

Fahim Zaman is a Staff Reporter for ‘The Science Survey.’ He enjoys journalistic writing due to being fascinated by the thought of exploring various...