After Byford, Now What for the MTA?

The new OMNY system is one of many improvements, having been implemented in May 2019 to streamline paying for fares. It is set to phase out the Metrocard by 2023.

“Train daddy loves you very much”— this is a phrase written across a series of stickers in Brooklyn stations that garnered enough attention that even Andy Byford acknowledged the nickname. Byford is the outgoing chief of transportation for the MTA, the state agency that operates the subways, buses, LIRR, and MetroNorth. The stickers are meant to show the level of respect he has gained from commuters through his actions, from riding the trains with customers to proposing bold new changes to the system to modernize it. His resignation on February 21st, 2020 shows that even the best of the best cannot succeed in bringing about change in the MTA, mainly because its structure is fundamentally flawed.

The subway was in a state of emergency when Byford came into his job in January of 2018. 2015 was the year of Pizza Rat and 2017 of a literal state of emergency, all while the system was still reeling from Superstorm Sandy in 2012. On-time rates were at 67%, one of the worst among major transit systems. The MTA hired Byford as president of the NYC Transit Authority to deal with the disarray of ambitious plans such as Fast Forward, a 30 billion dollar proposal to take the signal system into the modern era. There was a lot of excitement—and rightly so. Byford has been credited before for turning around systems in London and Toronto.

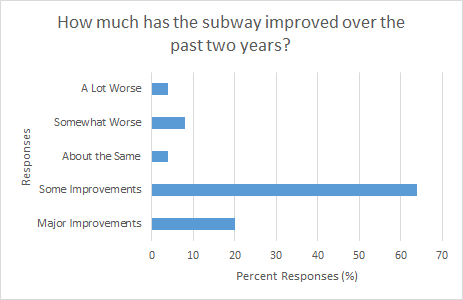

Responses from a sample of Bronx Science students regarding improvements to the subway during Byford’s tenure. 84% of all participants said there were minor or significant improvements in the system during Byford’s tenure.

Byford made progress during his tenure. On-time trains rose to 80%—a multi-year high. According to a poll of Bronx Science students that I conducted in person through interviews, 64% percent said there were some improvements over the past two years, and 20% said there were major improvements to the system during Byford’s time. However, Byford constantly received pushback from state officials, and despite his efforts, many of his proposals fell on deaf ears. Recent news articles highlight tensions between the state government and Byford, especially with Governor Andrew Cuomo. This was best exemplified by the disagreement over the L train closure for Superstorm Sandy repairs. Byford originally planned for the L train to cease operations between Brooklyn and Manhattan, but Cuomo later overrode that, instead keeping the train functional and pushing repairs to off-peak hours. There were also tensions between Byford and the state legislature, with his $40 billion plan to revitalize the subways and other policies as major points of contention. The final straw was when the role of Byford’s job was restructured by Cuomo giving him less bandwidth to operate. Constant back and forths between MTA officials and the state government and officials is not what the system needs.

Natalie Teng ’20, “… hopes that we can change the system so that there can be direct elections for the person responsible for the MTA.”

This is especially true now, as despite improvements made under Byford’s tenure there are still major hurdles to be cleared. These include a host of improvements from adding signals to improving accessibility that would place the subway system among the likes of Tokyo’s or London’s. With years of experience in transforming networks, Byford was an expert at what he did. He acknowledged the drastic overhaul the system would need to modernize to the future. The fact that experts like him were stifled from enacting necessary change due to a lack of understanding and ignorance is counterproductive.

Recent construction at the Astoria Boulevard station were part of the station’s modernization.

Accountability is also another pressing issue that is absent from the structure of the MTA. Byford was famously in tune with customers, methodically riding the subways with his name badge ready to take any questions or concerns. So then why should legislators in Albany—people that have no connection to the subway and probably seldom take it—be calling the shots on how it runs? Even though the MTA board has city and regional representation, most of the board is composed of members appointed by the governor. This is further clouded with representatives from neighboring counties that are not a part of the city who are stakeholders that also aren’t in tune with the system’s needs.

What if the MTA—at least the buses and subways that operate exclusively in New York City—were run by New Yorkers? If the MTA became a city agency, accountability would shift to the mayor. Natalie Teng ’20 said she “hopes that we can change the system so that there can be direct elections for the person responsible for the MTA.” The mayor and the city government in New York are all New Yorkers that understand the needs of their constituents. Considering how integral the status of the subways are to an average New Yorker, local officials would be a lot more adept to handle the ins and outs of the complex bustling network that’s the beating heart of New York City.

Akshay Raju is a Staff Reporter for ‘The Science Survey’ and Athletics Section Reporter for ‘The Observatory.’ He enjoys being able to write about...

Suzie Yu is a Online Newspaper Editor for the ‘Science Survey’ and an Athletics Section Reporter for ‘The Observatory.’ She finds journalistic...

Alisha Wang is a Staff Reporter for ‘The Science Survey’ and a Groups Section Reporter for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook. She finds that rhetoric...