Death of the Oeuvre

Coming to Terms with Problematic Authors

“I believe it’s okay for students to keep reading famous authors who are known to be racist as long as [the work] is acknowledged and read for literary technique as opposed to hateful content,” said Sophia Korono ’20, president of the Jewish Student Union, pictured here reading Sylvia Plath’s ‘The Bell Jar.’

The issue of whether to separate an artist from their art is certainly not a new one, especially when it comes to individuals who were, even for their time, far from politically correct.

Sylvia Plath (1932-1963) is mostly known today as a feminist poet, hailed and taught worldwide. But she was also a rabid anti-Semite. In addition to comparing her father’s abuse of her to the Holocaust in her poem ‘Daddy,’ Plath also wrote openly anti-Semitic and stereotypical descriptions of Jewish people in her journal.

So how do we separate Plath from these opinions – or should we bother trying at all? After all, many of Plath’s works don’t even mention her personal anti-Semitism –should we condemn those as well because of the small-mindedness of the woman who wrote them?

If you enjoy reading or watching works in the horror genre, chances are H.P. Lovecraft had something to do with it. The man who inspired Ridley Scott (Alien), Joss Whedon (Buffy the Vampire Slayer), and Guillermo del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth, The Shape of Water) was known for inventing the genre of Lovecraftian horror, defined as horror fiction emphasizing the fear of the unknown or the unknowable over gore and shock elements.

But he had a dark(er) side. ‘The Horror at Red Hook’, for instance, which is a short story about a detective investigating a rash of kidnappings and discovering ancient evils, is not an inherently racist story at surface level. And yet Lovecraft himself admits that ‘The Horror at Red Hook’ was inspired by his xenophobia in the below excerpt from a letter to a friend, fellow writer Clark Ashton Smith:

“The idea that black magic exists in secret today, or that hellish antique rites still exist in obscurity, is one that I have used and shall use again. When you see my new tale ‘The Horror at Red Hook’, you will see what use I make of the idea in connection with the gangs of young loafers & herds of evil-looking foreigners that one sees everywhere in New York.”

It’s easy to write off H.P. Lovecraft as a racist, but there is surely a reason his works are so pervasive and famous even to this day, to the point where Stephen King praised him as “yet to be surpassed as the Twentieth Century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale.” Are we expected to swear off Lovecraft entirely? And if so, does that mean swearing off works inspired by him as well?

At the end of the day, it’s an individual decision. It’s absolutely understandable if one cannot get past the sheer repulsiveness of the individual in order to read their work. But trying to have society “cancel” authors based on personal ideas infiltrating their works, or trying to separate the individual from their racist statements entirely as suggested in Roland Barthes’ ‘Death of the Author’ is too extreme.

First, it is impractical to attempt to remove authors so well entrenched in the literary canon. Second, these works -and the intolerant humans who wrote them -are still a part of literary history and should be taught as such. When reading Lovecraft for a better understanding of modern horror, Plath for confessional poetry, or even Oscar Wilde for a school assignment, we should not ignore their bigoted sentiments. We should continue to read works written or inspired by these people, as long as we are choosing to read them in the full context of who they were.

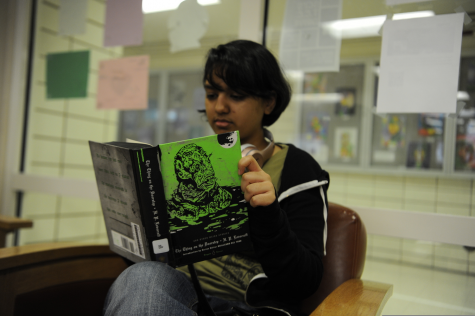

Subha Laskar ’20 reads ‘The Thing on the Doorstop’ by H.P. Lovecraft, found in the Bronx Science library.

We should continue to read works written or inspired by these people, as long as we are choosing to read them in the full context of who they were.

Sylvie Koenigsberg is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey’ and a Student Life Reporter for ‘The Observatory’ who is intrigued by the ways different...

![“I believe it's okay for students to keep reading famous authors who are known to be racist as long as [the work] is acknowledged and read for literary technique as opposed to hateful content,” said Sophia Korono ’20, president of the Jewish Student Union, pictured here reading Sylvia Plath's 'The Bell Jar.'](https://thesciencesurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/pasted-image-0-1-2-900x599.png)