Debt, Political Conflict, and Broken Signals: What’s the MTA Way to Fix NYC’s Subway System?

Suggestions for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority

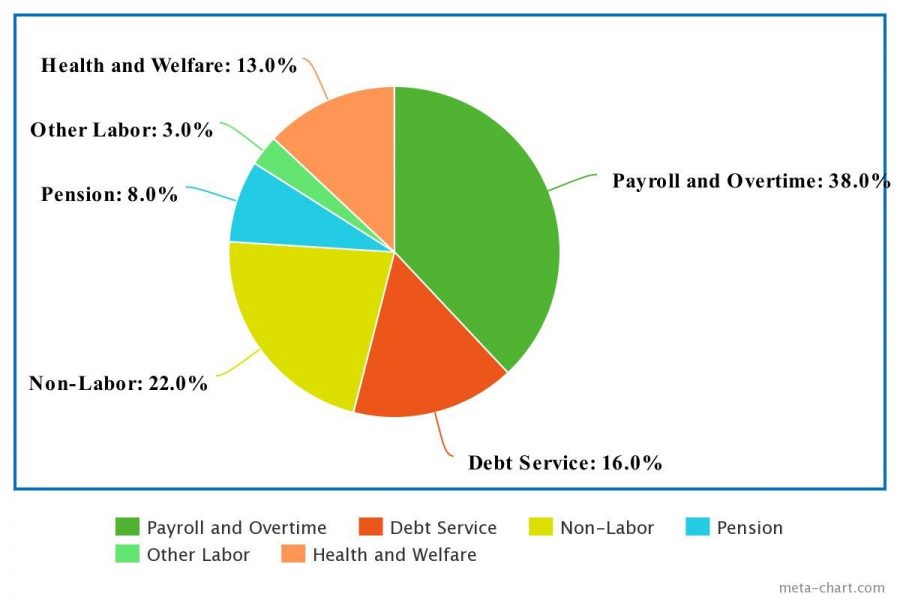

This pie chart depicts the general breakdown of the MTA’s spending for NYC transit, showing how major portions go towards paying off its debt and for political projects. Statistics are taken from the MTA 2017 Budget that is published online.

$40,044.08. This shocking number is the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s (MTA) debt, according to its online published debt budget as of 2018. The MTA is known for its delayed subways, but its debt has gone largely unnoticed. To understand this debt, it is important to know where it stems from, why it has continued to exist, and the problems within the MTA’s current system.

One reason for the pending debt is that the MTA’s budget was shaped to benefit politicians rather than the average New Yorker. It began all the way back in 1999, when Bear Stearns, a Wall Street investment giant, along with various politicians, helped come together to cover the MTA’s $12 billion dollar debt.

Politicians dictate how the MTA spends its budget. Much of the MTA’s money is still frequently used to fund politicians’ pet projects for personal benefit. These projects give politicians publicity and an appearance of goodwill without actually benefiting the transportation system itself. In 2017, the MTA wrote a five million dollar check to three upstate ski resorts under the Olympic Regional Development Authority (ORDA) who lost revenue from warm weather, despite being unrelated to the MTA. The reason why? “The MTA owes money to the state,” was New York Governor Cuomo’s answer. This decision is one of the many that have been passed even without the MTA Board’s approval.

The situation is comparable to viewing the state and city of New York as cheap customers at a restaurant, both refusing to pay the bill, dutch or solo, while the owner, the MTA, sits penniless, unable to move forward.

Though there is a seventeen member board for passing MTA-related decisions, the members are nominated by Cuomo himself, with four chosen by NYC’s mayor and the others from the other counties in New York State. Having members on both the Mayor and Governor’s sides presents conflicting goals. Although there is a Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee with MTA users, they do not have voting power, resulting in skewed decisions.

The glass-domed Fulton Street station in downtown Manhattan is another prime example of the MTA’s money being used for more personal reasons. Sheldon Silver, a Democratic politician who was the driving force behind building the 1.5 billion Oculus in the World Trade Center, threatened to veto the MTA’s capital budget if it was not built. Though MTA board members protested, they continued to build the station because of the financial threat. Though it was claimed to be built to organize the eight lines of Fulton Street, the Oculus mainly benefited Silver’s district by generating revenue. In this ten year project, not a single track or train was repaired at all, while debt keep piling up.

Many riders may think that the employees should be paid less to reduce the MTA’s debt because payroll makes up the largest portion. However, the Regional Plan Association and Empire State Transportation Alliance has noted that this portion has drastically dropped from 73% in 2003 to 53% in 2014, and has recently dipped further to 33% in 2017. Therefore, it is not the employees’ payroll that is the problem. As shown by projects like Fulton Street, the problem is that the money earned supposedly for the MTA is being spent in ways that is not improving any of its systems at all. Spending is skewed to benefit politicians because of the conflict between the governor and mayor on how to spend and earn more money for improvements. One plan that the MTA wants to implement is to modernize NYC transit, which is a 40 billion dollar proposal.

Though originally stating that his congestion plan for charging cars that entered Manhattan business districts to help get more funds, Cuomo later stated that he believed NYC should pay for this project instead of the state paying for it alone. Mayor de Blasio refused to comply with this statement, using a 1953 state law to prove how they had no legal obligation to contribute more than five million dollars. MTA chairman Joe Lhota referenced a 1981 law that stated that the city was responsible for the MTA’s capital needs with a board created solely for that purpose. New Yorkers are mainly concerned with the preposition that Cuomo’s congestion plan may not be able to bring in enough revenue to pay back costs, and that it will halt improvements. The situation is comparable to viewing the state and city of New York as cheap customers at a restaurant, both refusing to pay the bill, dutch or solo, while the owner, the MTA, sits penniless, unable to move forward. Now, there’s an eight billion dollar proposal for their current “Subway Action Plan,” designed to install better emergency water management and rails, faster response teams, and more countdown clocks. However, source of funding for this project still remains up in the air.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are being held temporarily. We thank you for your patience,” is the all too familiar message announced by the subway conductor. Bronx Science subway commuters dread train delays, especially at 7:00 A.M. The reason why the MTA experiences so many delays is because of the outdated signaling and safety systems. The current signaling system only tells commuters the section the the subway is in, rather than the exact location. There are two main signals in stations to help regulate train speeds.The one at the beginning of the track triggers a timer every time a train crosses. The second signal is at the end of the track. If the train reaches this second signal faster than the speed limit imposed, it automatically activates the train’s emergency brakes. Both these signals help to regulate the speed and location of different trains in order to try to prevent collision and accidents.

However, these signals were both installed incorrectly as reported by the MTA, and are currently poorly maintained, causing the entire system to be slowed because they are being braked at speeds below the limit. The additional harsh penalty of subway employees for tripping these signals adds to the delays. If they trip a signal too many times (which happens if they are automatically braked), the train operators face penalties ranging from losing vacation days to being forced into retirement. This means that in order to keep their jobs, many operators are told to slow down for all signals, in case the signals are faulty. For safety, the MTA has also increased the amount of space required between trains in the past years to reduce the chance of accidents. With harsh consequences and faulty signals, MTA trains do not get anywhere on time.

Tiffany Chen ’19, a past rider of Vallo who now takes the subway daily, can attest to these delays. “Though I don’t miss the financial cost of Vallo, I miss sitting on a bus comfortably every day. Taking the subway daily always makes me have to wake up earlier, because I have to account for the delays and how missing that one train will make me late,” she said.

In addition, the MTA’s implementation of a track safety task force adds to the inefficiency of the system. This organization was created due to two deaths of track workers in 2007. Before the force was created, only a single track was affected when there would be track work. However, now all the neighboring trains next to the track being worked on is now given a “slow zone” restriction, where the trains now have to travel thirty miles per hour slower than the speed limit, which ends up being less than ten miles per hour.

Overall, train delays are a domino effect. Though the MTA’s faulty signals and speed restrictions are intended to prevent accidents, the MTA lacks an incentive to improve the root of the problem — the faulty signals. The company has claimed that its main problem is overcrowding, but this contradicts the statistics calculated by ‘The New York Times.’ The findings show that the number of MTA riders has decreased by two percent over past years because many residents opt to use services like Uber and other private services, in order to be punctual.

Don’t get me wrong, as a fellow New Yorker, I adore the MTA for its accessibility, convenience, and city vibes. It is a blessing, because not everyone can say that they can grab a slice of pizza at 2 A.M. from across Manhattan, or hop on a subway to visit Central Park on a whim. However, the MTA system needs to address its delays because they are affecting other aspects of society. Delays can cause people to be late for anything as important as court hearings to anything as simple as a lunch date.

Specifically, Bronx Science students need to be on time given most of our hour-long commute. It’s time for people to ask politicians more about how they are going to improve transportation in New York. New Yorkers need to be more politically active about the transportation concerns of their city and call for both the city and state to support better transportation within the Big Apple. To truly get the MTA improvement projects on track, less of the budget should be allocated to political projects and should instead be allocated for the better good of the city.

Mian Hua Zheng is the Editorial Editor for ‘The Science Survey,’ and a Sidebar and Captions Editor and Academics Section Staff Reporter for ‘The...